Published 01 November 2022

The success of Chinese enterprises has benefited from the faulty assumptions of Western business leaders and policy makers. A failure to understand the role of the Chinese state and the country's operating environment gives false hope that somehow China isn’t different from the rest of the world.

China’s economic success story, complete with the exponential growth of its economy and rising standard of living of its people, has been well documented. Less codified is the rise of China Inc. This gap matters because it’s Chinese companies that ultimately drive the economy and are the instruments of world trade. In 2020, China dethroned the United States by number of companies on the Fortune Global 500. In 2021, China extended its lead with 13 more firms on the list than the US (135 vs. 122). Today, China not only has a growing number of giant firms, but its largest firms are growing much faster than its overall economy and much faster than those in the US and Europe. These firms are not only powerhouses in China but are extending their reach globally.

Chinese enterprises certainly deserve credit for their smart strategies and hard work. But they also have benefited from flat-footed and inattentive Western business leaders and policy makers. As we report in our upcoming book, Enterprise China: Adopting a Competitive Strategy for Business Success, the failure of Western businesses is rooted in significant misperceptions and misplaced assumptions about business in China and Chinese businesses. Here we discuss four key assumptions that Western leaders often get wrong.

Assumption 1: Competing with China is about understanding large, individual enterprises in China.

False. Most Western executives, as they are trained to do, analyze the competitive strategies of suppliers, strategic partners, or commercial rivals with the individual company as the unit of analysis. Sadly, this approach is fatally flawed when it comes to China. While Western executives focus on independent, multibillion-dollar enterprises, they miss the multitrillion-dollar monolith that we call Enterprise China in our book. This monolith consists not just of a particular company in focus, but an entire ecosystem of companies tied together by the largest entity on the planet by employment and the second largest by revenues — the Chinese state. It includes over 150,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) at the central, provincial, and municipal levels. Collectively, SOEs bring in more than $9.8 trillion in revenue and constitute about half of China’s market capitalization. Their economic production is about the same as the nominal GDP of Germany and larger than the economies of India and France.

But contrary to the image in the minds of most foreign executives, the Chinese state is not working behind closed doors in smoke-filled rooms, whispering its desires to commercial entities hoping that they will listen. No, the state operates in the open. It has publicly declared its competitive strategy and guides the 30% to 40% of the economy it directly owns and controls, while influencing the actions of the important commercial enterprises it doesn’t directly own and control. Our book refers to these entities as state-influenced enterprises (SIEs). We only need to look at how Beijing forced the recent delisting of Didi for evidence of the level to which the state calls the shots.

Assumption 2: China is destined to be the number one economy and take over the world.

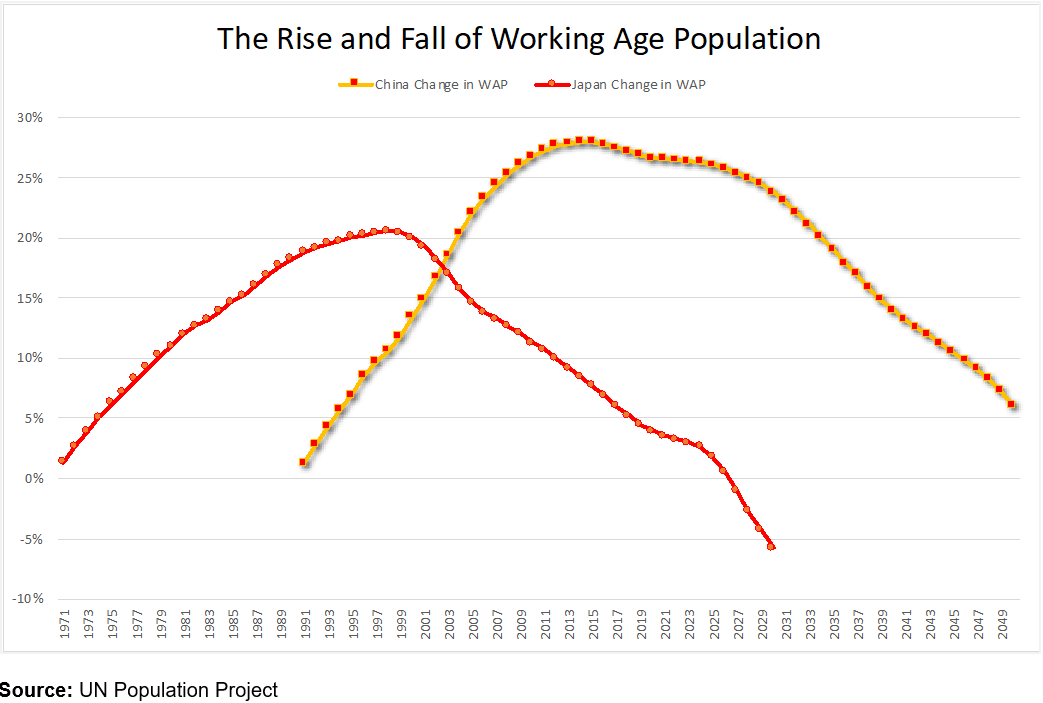

False. China’s economic growth trajectory, together with the growth of giant Chinese enterprises, has convinced some that the country will soon become the largest economy on the planet by nominal GDP, and that its firms will dominate world markets. However, several factors could easily derail China. First, internal political conflicts may emerge that further slow or reverse the country’s decades-long growth trajectory. Second, the United Nations estimates that China’s working population will go into steady decline over the next 30 years, and nothing will reverse this course because its birth rate has been dropping for more than 50 years and shows no signs of ameliorating. While coming several decades later, China’s decline in population seems to mirror that of Japan. Like Japan, China soon will (a) not have enough workers at the bottom, and (b) not generate enough productivity to offset the negative effects of its shrinking workforce. This will increasingly undermine the global competitiveness of Chinese enterprises and could easily stall economic growth, as happened in Japan for the last 20 years since its working population peaked and started its decline.

In theory, China could compensate for its shrinking working population by ratcheting up its labor productivity. 2015 saw China’s peak in working population numbers. During the 20 years prior, China’s annual productivity gains averaged an impressive 13.8% (slightly higher than Japan’s 13.0%). However, a more granular examination reveals that in the last four years, China’s productivity growth averaged just 5.7%. In other words, its productivity growth rate was slowing just as it needed to accelerate.

Reviving China’s productivity growth won’t be easy. Unlike the 1980s when new equipment could dramatically increase productivity for the entire economy, China’s enormous size makes similar productivity gains now unlikely. Furthermore, the gains in productivity China reaped from nearly 300 million rural residents migrating to urban areas, loaded with modern machinery and technology, seem to have run their course.

Assumption 3: What happens in China stays in China.

False. Many analysts are fond of the notion that China is on the path to decoupling from the West and forming a separate economic system for itself and its satellites across the planet. Following this theory, many companies believe that they can insulate themselves with an “in China for China” strategy, tailoring their domestic output to mainland markets. This strategy is difficult for two fundamental reasons. First, the level of investment and management attention necessary for a foreign firm to be considered an “insider” in China is tremendous. One only needs look to Honeywell for an example of the level of investment, adaptation, and length of commitment to see what is required. Consider that the former head of Honeywell in China, Shane Tedjarati, spent nearly 20 years there, learned to speak Chinese fluently, and the company invested billions in creating products that were only sold in China.

Even with these levels of commitment to being “in China for China,” the impact of a firm’s actions and reputation cannot be confined within national borders in today’s interconnected world. As we report in Enterprise China, foreign firms’ actions in China can affect their reputations outside China in two ways: cross-cultural misunderstandings and excessive integration with the Chinese state.

Because China is so culturally different from the West, embarrassing missteps are easy to make. In 2018 Dolce & Gabbana produced a promotional video attempting to show the challenge of eating spaghetti with chopsticks. It was a reputational disaster, news of which spread quickly around the world. Likewise, when a McDonald’s franchise in China’s southern Guangdong Province displayed a sign saying that “black people are not allowed to enter,” what happened in China did not stay there. The reputational damage was impossible for McDonald’s to contain.

Likewise, Western companies that are perceived as too cozy with the Chinese state risk damaging their global reputations. To comply with the state, a wide range of companies with important operations in China, including Coach, Marriott, Swarovski, Medtronic, Audi, Calvin Klein, McDonald’s, Delta Airlines, and the National Basketball Association, have felt it necessary to publicly apologize to China for “inappropriately” referring to Taiwan or Hong Kong as countries in their ads or other marketing materials they have produced. However, these apologies to China did not stay in China. They were viewed by many outside China with disdain, thus undermining those company’s global reputations.

Beyond appeasing the Chinese state, Western companies face an even larger challenge: responding to rules and regulations that are inconsistent with their home country’s values and norms. Many of these rules govern the collection and sharing of sensitive data with the Chinese state. In 2021, Apple opened a data storage center in the southwestern city of Guiyang to house the personal information of its Chinese customers. However, as part of Apple’s grand bargain with the Chinese, the plant’s operations were largely turned over to an SOE that was given access to the digital keys that controlled its encryption algorithms. This was contrary to privacy protection policies and norms in the US to many observers, it appeared that Apple had one set of rules for China and another for the rest of the world.

Western companies also face very real direct competitive challenges when they fail to accept that what happens in China rarely stays in China. Consider the case of Kawasaki Heavy Industries. In 2003, China began to pursue a long-term plan to create an internationally competitive high-speed railway system. Phase one involved creating 74,500 miles of new high-speed track designed to link major population and industrial centers in China. To achieve its goals, the country gave foreign companies access to China, contingent upon their forming joint ventures with Chinese firms and agreeing to share their technology with Chinese producers. Kawasaki Heavy Industries, as well other global companies, warmly responded and agreed to assist China in creating a family of rail technologies. Over time, restrictions on Kawasaki and other foreign companies increased as China’s local manufacturers moved up the learning curve and value stack, from freight trains to light rail and then passenger trains. The Chinese state then orchestrated the merger of two state-owned rail companies to create CRRC Corp., giving the rolling-stock maker monopolistic control of the domestic market. Through forced joint ventures, in 2007, the country introduced its first high-speed rail line based on “borrowed” Western technologies including those sourced from, among others, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, a key developer and producer of Japan’s Shinkansen bullet trains. To support its ambitions, in 2016 the state committed a whopping $549 billion to upgrade and expand the country’s rail network, with most of the investment targeting high-speed trains. The country then moved to effectively shut foreign firms out of key Chinese markets and segments. The final phase of China’s plan involved globalizing Chinese rail technologies and equipment. By accessing state funding, CRRC has been able to underbid foreign competitors by 20% to 30% on equipment sales opportunities in the United States and Europe. In 2019, China exported $37.3 billion in rail equipment — greater than the total sales of any global competitor. Kawasaki has seen its global market share plummet because it mistakenly assumed that what happens in China stays in China.

Assumption 4: Being the best will win the day in China.

False. According to conventional thinking in the West, the biggest rewards follow those who are the best at what they do. Better technologies produce lower costs, more innovative products, improved customer responsiveness, and so on. Sadly, this is not often the case in China. At least not in the long run.

Consider the case of Fresenius Medical Care, based in Germany. It is a top 10 medical device maker globally, but its products sit in the crosshairs of Beijing’s strategic “Made in China (MIC) 2025” goal to wean itself from foreign technology. Consequently, and irrespective of the high quality of its offerings, Fresenius has fallen victim to China’s national champion, Mindray. Mindray is more than twice as large as its closest domestic competitor, and it is growing faster in China than any of its major foreign rivals, including Fresenius. This growth is spurred largely by national and provincial government officials directing Chinese hospitals to increase their purchases of domestically sourced medical devices to 70% of such expenditures, in line with the strategic objective of reducing external dependencies through local content and import substitution as directed by MIC 2025. Fresenius’ survival in China at a comparatively small scale, when national champions such as Mindray are looking to dominate domestically, will require from Fresenius unassailable product superiority, discounted pricing, and superior distribution. While they may be among the best globally, the forces in China driving domestic domination and self-sufficiency make the long-term success of the likes of Fresenius look dim.

China really is different

Chinese enterprises deserve significant credit for their inroads in global trade and competitiveness. However, they have also benefited from the faulty assumptions of Western business leaders and policy makers. We have highlighted four key assumptions that these leaders often get wrong. There are many more. Accepting false assumptions gives a false hope that somehow China isn’t really different from the rest of the world. This in turn has caused foreign executives to mis-calibrate the risks and opportunities, and consequently miscalculate their strategy and actions in China.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).