Published 10 February 2017

With $373 billion invested in our economy, it’s no wonder that Japan has an interest in maintaining close economic relations and seeing the U.S. economy succeed. When Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meets with President Trump this week, Abe is expected to present his “U.S.-Japan Growth and Employment Initiative,” a gesture that reflects that commitment.

More than thirty years of serious investments by Japanese firms in American communities and workers is not the stuff of theater.

Why Foreign Companies Invest in the United States

Foreign companies want to invest or set up shop in the United States more than anywhere else in the world. They are attracted to our large and dynamic consumer market, our educated and productive workforce, transparent regulatory environment, a culture of innovation and a financial system that supports and rewards entrepreneurism.

Despite efforts by other countries to draw a bigger share of those investments, the United States had garnered nearly $3 trillion in cumulative foreign direct investment by the end of 2014.

Japan is an Early and Often Investor

Eight countries account for 80 percent of foreign direct investment in the United States. Japan is the second largest source of investment, just behind the United Kingdom, and Japanese companies invest more in the United States than in any other foreign country. (The feeling is mutual – the United States is Japan’s largest investor. More than 7,000 American subsidiaries are present in all of Japan’s 47 prefectures.)

With $373 billion invested in our economy, it’s no wonder that Japan has an interest in maintaining close economic relations and seeing the U.S. economy succeed. When Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meets with President Trump this week, Abe is expected to present his “U.S.-Japan Growth and Employment Initiative,” a gesture that reflects that commitment.

The Initiative reportedly proposes Japanese investments in U.S. high-speed trains and other key infrastructure projects, as well as joint development of robotics and other technologies, all of which could generate some 700,000 jobs in the United States.

The Largest Existing Investments are in U.S. Manufacturing

Foreign companies invest all across the U.S. economy, in finance, banking and insurance, in professional and technical services, in utilities, transportation, warehousing, real estate, and retail. But the single largest industry attracting investment is manufacturing.

More than $1 trillion – more than one-third of all foreign direct investment – is directed to manufacturing operations in the United States. Japan is a leader in manufacturing investments in the United States, inducing investments and generating spillover gains in productivity throughout the value chain for suppliers, service providers and retailers – like the auto dealerships that sell Japanese brand autos made in the United States.

With $373 billion invested in our economy, it’s no wonder that Japan has an interest in maintaining close economic relations and seeing the U.S. economy succeed.

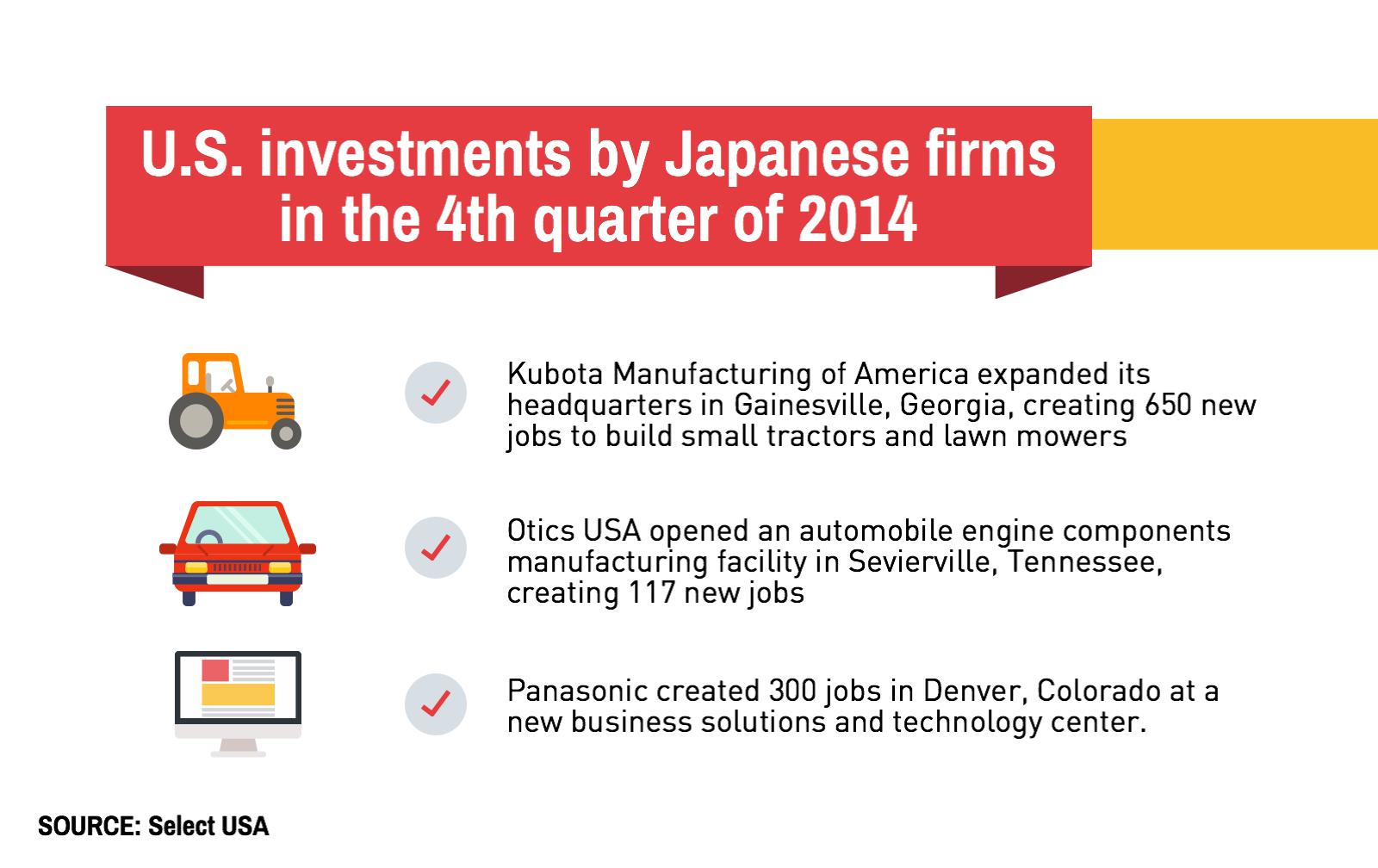

Japanese Firms Employ 839,400 Americans

In 2014, 839,400 Americans were employed by majority-owned Japanese subsidiaries in the United States – household names like Panasonic and Toyota.

Japanese Investments Generate a Good Return

Foreign affiliates in the United States paid wages and compensation that averaged nearly $80,000 per U.S. employee in 2013, compared with the economy-wide average of $60,000.

Japanese firms pay higher than average wages and spend more on R&D per American worker than the average foreign firm. As among the largest and most technologically sophisticated sources of foreign direct investment, Japanese firms contribute significantly to U.S. productivity, adding $93 billion to the U.S. economy in 2012.

Foreign Affiliates are Dynamic Traders

Foreign firms in the United States accounted for nearly 23 percent of U.S. goods exports in 2013; they also accounted for nearly 30 percent of imports in 2013, affording the United States extensive and diverse links to the global economy.

Overall, the United States logged $110 billion in exports of goods and services to Japan in 2014. The East-West Center created an interactive map of the United States that allows you to see how much each state generated in exports to Japan.

For example, Texas sold $9 billion, California $20 billion, and Illinois $4.8 billion. United States and Japanese firms maintain a dynamic and extremely important two-way trading relationship, fueled in large measure by the extensive and long-term investments Japanese firms maintain in the United States as part of the fabric of the U.S. economy.

Foreign affiliates in the United States paid wages and compensation that averaged nearly $80,000 per U.S. employee in 2013, compared with the economy-wide average of $60,000.

Is a US-Japan free trade agreement in the cards?

Watch this space. The Trump Administration withdrew from the Transpacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) on day one of its term, and seems inclined to favor smaller trade deals with strategic partners. Among the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) participants, Japan is the most obvious to peel off, given the United States’ close economic, political, and security ties.

The driving economic rationale remains valid: Japan offers a lucrative market for U.S. products despite continued barriers to greater market access in key sectors. American farmers are particularly keen to unlock more sales in Japan, which is already the fourth-largest export market for U.S. agriculture. For Japan, a trade agreement would buttress badly needed, but politically difficult, structural reforms to promote stronger growth of their economy.

Most of the really hard work was achieved in the course of negotiating TPP, and in Japan’s case, approving TPP. Maybe all of the effort can be salvaged in the form of a bilateral free trade agreement among between two important allies.

Feature photo credit: tx.english-ch.com

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).