Published 30 May 2023

While digital technologies may be ubiquitous, regulations applied to digital trade remain disjointed. Governments are now seeking to strengthen digital borders to retain national sovereignty on the internet. The proliferation of digital trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific and beyond could risk exacerbating fragmentation.

Over the last decade, and particularly since the start of the pandemic, a new trade ecosystem has emerged in which digital technologies enable new products and services, create new channels for trade, and develop new ways to move goods and services across borders.

To put some numbers around these trends, in 2022, domestic and international data flows – the lifeblood of digital trade – were forecast to exceed the volume of all internet traffic up to 2016.1 Trade in digitally-deliverable services has expanded fourfold since 2005, faster than for goods and non-digital services.2 The e-commerce market is projected to reach US$4.11 trillion in 2023.3 “TradeTech” is increasingly smoothing the past for all kinds of trade.4

More digital means more fragmentation

While digital technologies may be ubiquitous, the rules applied to the digital economy remain disjointed. As global digital trade has expanded, policymakers have struggled to keep up. Governments are belatedly seeking to erect digital borders to retain national sovereignty on the internet, particularly through new rules that govern data flows. To paraphrase Taylor Swift, regulators gonna regulate.

But these approaches often pay little heed to interoperability and may not in any case be fit for purpose in a rapidly changing environment. A recent Global Trade Alert report describes the process since 2020 as “regulatory overdrive”, with governments initiating nearly 3,000 legal and regulatory steps over the last three years.5

In other cases, regulatory guardrails have yet to catch up, particularly to frontier technologies. Of greatest concern is artificial intelligence, which will be increasingly important for trade, and for which trade rules will in turn have major implications for innovation, uptake, and governance. Yet few such rules are currently in place.6 Similarly, digital identities are a critical enabler for trust and integrity in cross-border transactions and supply chains, but governance within and across markets is patchy at best.7 It could be said that in effect, we are building the plane while flying it.

The cost of fragmentation

For businesses, this is a headache. Having to retool products and services to meet different requirements across multiple markets is costly. A lack of clear regulatory settings or overly burdensome requirements can make business planning difficult and trade risky. Heterogeneity can also result in regulatory arbitrage, where businesses make strategic decisions about markets to take competitive advantage of more favorable jurisdictions.

Regulatory uncertainty also potentially undermines the social license for trade: in the digital economy, perhaps even more than for other forms of trade, trust is a prerequisite to engagement. Similarly, policymakers seeking to safeguard public policy goals such as privacy and cybersecurity may struggle to achieve good outcomes in a fragmented landscape, since these require cross-border coordination. Hackers are rarely polite enough to limit their activities within national borders.

Lastly, regulatory heterogeneity is a problem for economic development and small businesses. Developing countries already face a significant capacity gap in digital trade policymaking.8 With some notable exceptions, recent digital trade rules are being written without large numbers of developing countries at the table – making it all the more daunting for small businesses from those economies to navigate an increasingly complex regulatory environment.9

The three digital kingdoms

Most of the action in designing cross-border digital trade rules is taking place in free trade agreements. Over half of all trade agreements signed since 2000 include at least some digital provisions, if not dedicated chapters on digital rules.10 Many of these agreements are in the Asia-Pacific, including three “mega-regionals”: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and the United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement (USMCA).

Digital chapters in the region’s FTAs typically include data governance and related rules, on data flows, where data must be stored or processed (“forced data localization”), personal information protection (or privacy), open access to the internet, source code, and Customs duties on electronic transmissions. These FTAs also include provisions on trade facilitation and consumer protection.

Data governance is the source of considerable friction. While all the major regional models ostensibly support cross-border flows of data and reject forced data localization, there is a wide gulf between RCEP, which allows broad and self-judging exceptions to this rule, and CPTPP/USMCA, which contain more limited exceptions. These approaches can be loosely described as the “US approach” (CPTPP/USMCA) and the “Chinese approach” (RCEP), along with the “EU approach” (which takes a privacy rights-based approach) forming three distinct global “data realms” or “digital kingdoms”.11

Adding to the complexity of the data landscape, the International Group of Seven economies announced in April 2023 that they intended to operationalize Japan’s concept of “Data Free Flow with Trust” (DFFT). A “principles-based, solutions-oriented, evidence-based, multistakeholder and cross-sectoral cooperation” will look at data localization, regulatory coherence for cross-border data transfers and privacy-enhancing technologies, among other issues.12 While this will likely enhance coherence across the G7, it may also add a further layer of complexity vis-à-vis others.

The new kid in town

Over the last three years, a new kind of trade agreement has emerged: “digital economy agreements” (DEAs). DEAs do not cut the Gordian knot of data governance, though they do include interesting new approaches – for example, around more trade-friendly treatment of financial services data flows – as well as provide a platform to build confidence and unlock collaboration on how to balance data flows and public policy goals.13

Beyond data governance, however, the DEA model is both novel and useful in several ways. First, it represents a departure from the scope of “digital trade” in earlier FTAs. Where the latter set rules for digitized trade, the DEAs contemplate a more digitalized process which leverages the full innovative potential of the digital economy – think interoperable blockchain-based trade finance, rather than an email of a scanned copy of a customs declaration. Data flows matter to businesses; but doing business successfully in the digital economy requires a far wider range of enabling settings.

The poster child for this approach, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), puts it best by describing its own remit as “trade in the digital economy”. The DEPA includes not only the earlier FTA provisions, but also aims to enable end-to-end digital trade transactions and trust, for example by focusing on the interoperability of approaches such as paperless trade, e-payments, e-invoicing, e-contracts, e-authentication and e-signatures and trust marks, among others.14

Further, the DEPA and other DEAs provide a platform to co-design responsive rules across a raft of broader ‘digital economy’ topics. The collective tally of DEA topics is sizeable, including emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, digital identities, fintech, regtech (regulatory technology), and even “lawtech” (legal technology); data innovation and regulatory sandboxes, open government data, cryptography, standards, inclusion for small businesses and other groups, a safe online environment, infrastructure and logistics, and even regional capacity building.

Too much of a good thing?

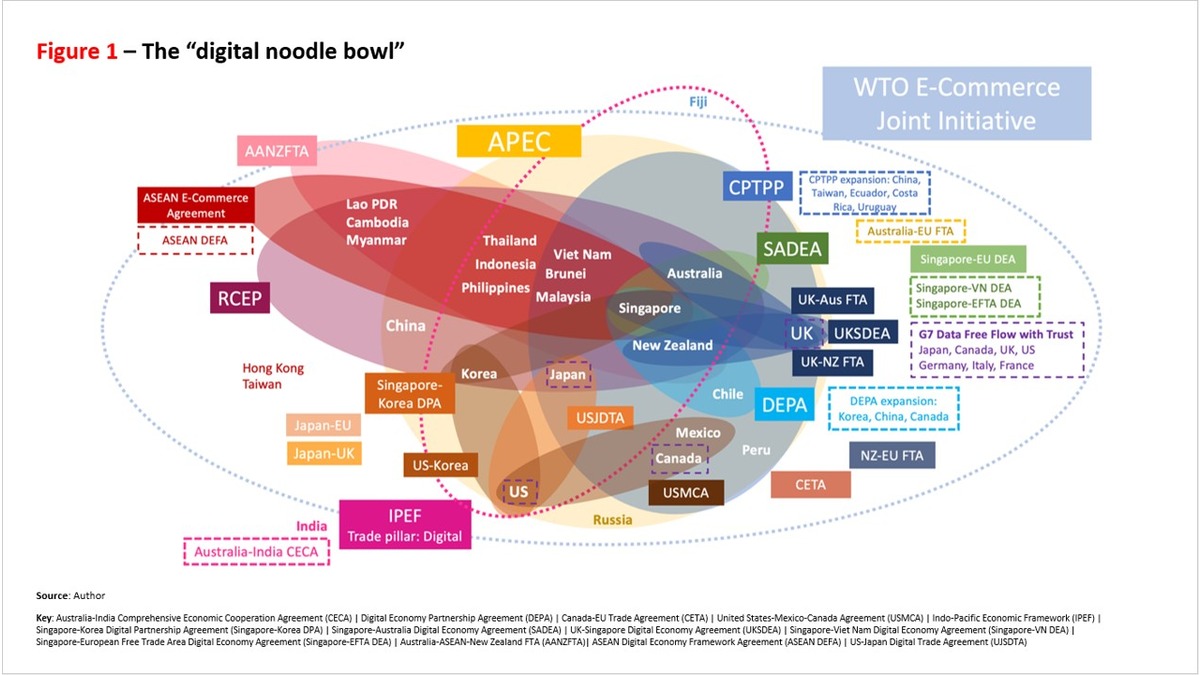

While the scope and ambition are welcome, the proliferation of these new agreements in the Asia-Pacific and beyond (as Figure 1 illustrates) risks exacerbating fragmentation. Many of these new initiatives are bilateral, or among a ‘closed shop’ of a small group of countries. While such agreements will undoubtedly contribute to more seamless digital trade, they do little to tackle broader digital regulatory heterogeneity.

Creating coherence across the broadest possible set of economies is the first-best approach for digital trade. The influence of DEAs on the approaches of the larger players, including China, the US and EU, is starting to be visible: China wants to join DEPA, the EU is negotiating a DEA with Singapore, and there are DEA-like elements to the US’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework negotiations. Ultimately, though, developing “global” rules through the WTO is the optimal approach, and there are some promising signs emerging from the WTO Joint Initiative on e-Commerce, although it seems likely to end up at a relatively low-ambition modus vivendi on data flows, at least.

In the meantime, the DEPA would seem to be the most promising building block. It is designed and branded as an “open plurilateral”, complete with an accession mechanism and enthusiasm from the founders for expansion. Korea is close to acceding, and Canada, China and most recently in the margins of the APEC Trade Ministers’ meeting, Peru, have all applied to join. There must be a strong case at least to triangulate with others in the region which have already negotiated similar DEAs, including Australia and the UK, if not a wider group of RCEP and CPTPP members.

As for the latest cab off the rank, the jury is still out on whether IPEF will ultimately reach binding commitments on digital trade rules. It is not at all clear whether the participants, especially less developed economies, such as Fiji and Viet Nam, will have the appetite to agree potentially sensitive far-reaching regulatory commitments in some areas without concessions on market access. And unless IPEF also seeks to bring along a broader group from the region, including those that may not be considered “like-minded”, it risks giving impetus to the forces of fragmentation – taking us ever further away from a seamless global digital economy.

***

[1] UNCTAD (2022), Digital Economy Report 2021.

[2] ADB (2022), Unlocking the Potential of Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific, eds. Kang, Jong Woo, Helble, Matthias, Avendano, Rolando, Crivelli, Pramila, Tayag, Mara Claire, November 2022; UNCTAD, 2 December 2022, ‘Supporting countries to measure the digital economy for development’.

[3] Statista Digital Market Insights.

[4] WTO and WEF (2022), The Promise of TradeTech – Policy approaches to harness trade digitalization.

[5] Evenett, S. And Fritz, J. (2022), Emergent Digital Fragmentation – The Perils of Unilateralism; and Digital Policy Alert.

[6] Jones, E. (2023), ‘Digital disruption: artificial intelligence and international trade policy’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Volume 39, Issue 1, Spring 2023.

[7] Honey, S., (2022), Digital Identity in APEC – Deepening Trust, Inclusion and Interoperability in the Digital Economy, Report for the APEC Business Advisory Council.

[8] Asian Development Bank (2022), Aid for Trade in Asia and the Pacific: Leveraging Trade and Digital Agreements for Sustainable Development.

[9] Mishra, N. (2022), ‘Can trade agreements narrow the global digital divide?’, Hinrich Foundation.

[10] Burri, M. (2023), ‘Trade Law 4.0: Are We There Yet?’, Journal of International Economic Law, Issue 25 - forthcoming.

[11] Aaronson, S. and Leblond, P. (2018), ‘Another Digital Divide: The Rise of Data Realms and Its Implications for the WTO’, Journal of International Economic Law; Gao, H. (2022), ‘Data Sovereignty and Trade Agreements: Three Digital Kingdoms’, Hinrich Foundation.

[12] G7 Ministerial Declaration, The G7 Digital and Tech Ministers’ Meeting, 30 April 2023.

[13] Singapore-Australia Digital Economy Agreement, Article 25.

[14] Honey, S. (2021), ‘Enabling trust, trade flows and innovation: the DEPA at work’, Hinrich Foundation.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).