Published 04 August 2017

In 1927, people throughout the United States were introduced to the white gospel of country music made possible by new portable recording devices and distributed by album and broadcast radio. In 2016, paid subscriptions to music streaming services topped 100 million. The recorded music industry is at the forefront of the explosion in global digital trade.

The Bristol Sessions

During this week in 1927, Ralph Peer, a record producer from Victor Talking Machine Company in New York City, set up a makeshift recording studio in Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia. His goal was to capture and disseminate the unique vocals, rhythms, and pickings of performers in southern Appalachia who represented the best of “hillbilly music.” Those acts included The Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Alfred G. Karnes and others who would become music legends and whose styles influence country, bluegrass, and folk artists to this day.

It’s for this reason that music historian Nolan Porterfield called the 1927 Bristol Sessions the “Big Bang of Country Music.” But there are other aspects to the big bang. Peer is thought to be the first agent to pay royalties to his recording artists. For their Bristol sessions, artists were paid US$50 (worth around US$700 today) on the spot for each side cut, and 2½ cents for each single sold. And it was the portability of the Victor Company’s new electronic recording process that enabled Peer to bring his state-of-the-art equipment and recording engineers to the musicians, most of whom had never set foot in the “big city” of Bristol, let alone ever have the chance to record in New York. And so, artists like El Watson could be discovered by the recording industry, and their music shared with the listening public.

Vinyl revival? Nope, it’s about global streaming.

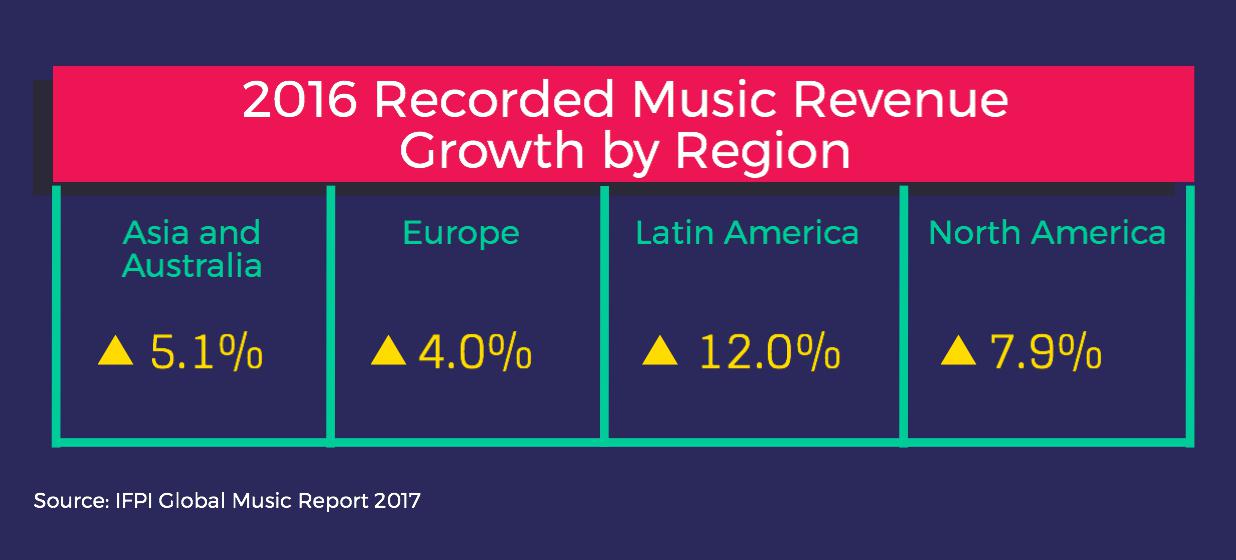

The Bristol recordings demonstrated the widespread appeal of southern gospel. The albums sold well and were picked up on broadcast radio, the two primary ways people could access music then. Today, the recorded music industry is going through an entirely different big bang. Last year the industry recorded 5.9 percent growth, which is being hailed as a 20-year high, but think of the context: the industry lost 40 percent of its revenues over the last fifteen years. That’s in large part because the artists, agents, and record companies are trying to figure out how to adapt pre-digital revenue models to the many ways people can access musical recordings today.

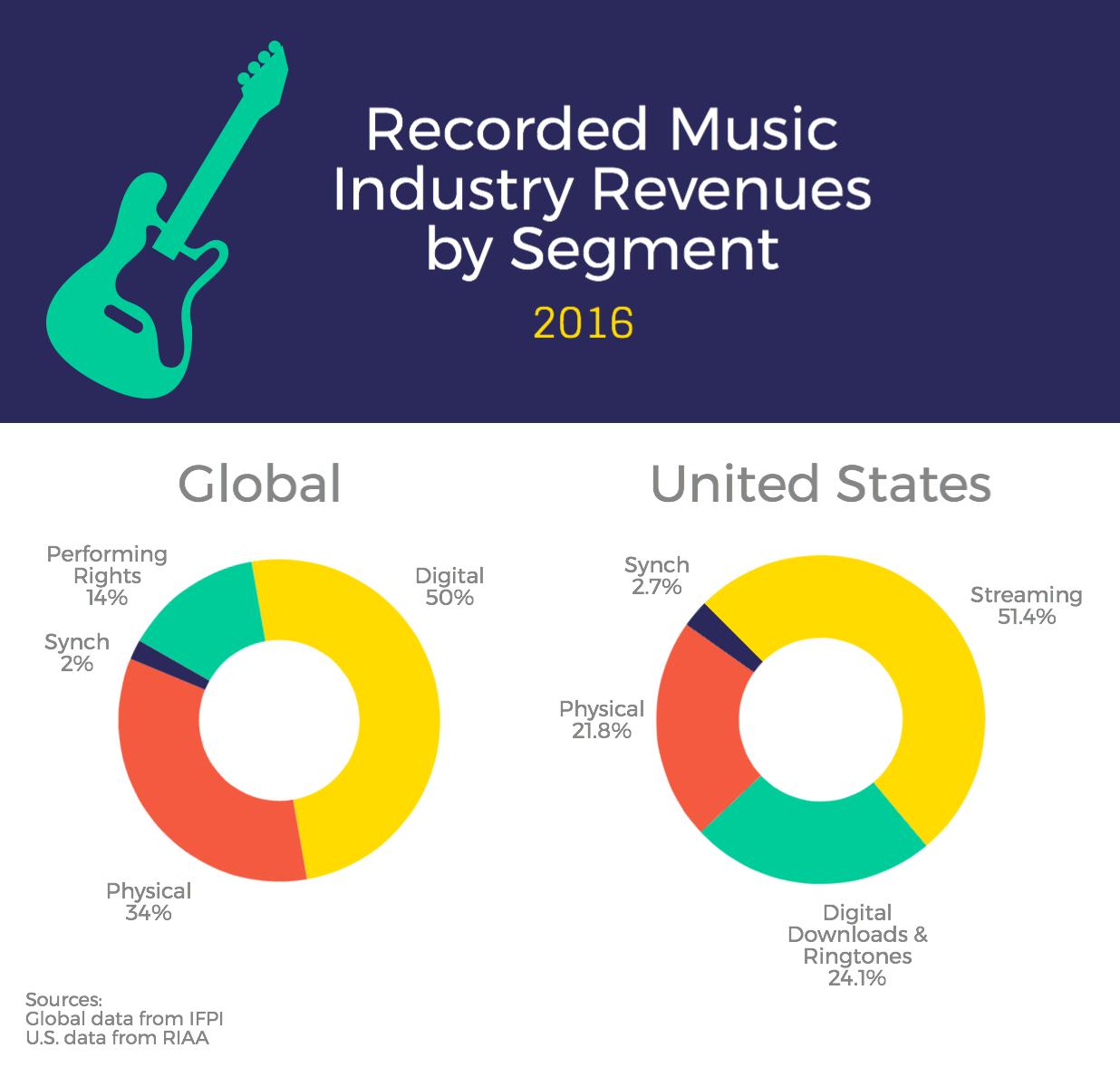

Is music streaming the next big bang? Streaming surged by 60.4 percent in 2016 alone, with over 100 million paid subscriptions to streaming services worldwide. In 2016, just 14 percent of revenues came from performing rights, 2 percent from synchronization (when recorded music is incorporated into ads or films for example), and 34 percent was derived from sales of physical recordings like CDs and albums (thanks to Japan and Germany). Digital sales generated the remaining 50 percent of revenues largely from streaming versus digital downloads. In twenty-five global markets, digital revenues exceeded 50 percent of the overall market.

From Southern Appalachia to North Africa

Streaming presents as many challenges as opportunities, from the ability of the artists to secure fair remuneration to creating new pathways to piracy. But the bright upside according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), is that streaming is enabling access to many more listeners in markets like Russia, Brazil, and Mexico and in some cases creating a recorded music market where none existed before – markets the industry wrote off due to piracy.

Streaming services are extending their reach as multinational leaders like Spotify (from Sweden) and Apple make inroads in new markets. Regional and national music streaming service providers are also blazing trails, including Anghami in the Middle East and North Africa, Saavn and Gaana in India, Line and KKBox in Japan and across South East Asia, UMA Music in Russia, and QQ Music, Kugou and Kuwo in China.

The streaming industry’s growth is tracking the rapid acquisition of cheaper smartphones in developing markets. IFPI notes that mobile streaming is fueling a resurgent business for the recorded music industry throughout Latin America, for example, where revenues grew 12 percent last year.

Could paid subscriptions help reduce piracy?

The digital market is driving global growth of the recorded music industry, which is emblematic of why copyright-based industries are keen to work with other countries to bring their domestic copyright protection and enforcement mechanisms up to international standards. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) estimates there were over 137.3 billion visits globally in 2016 to websites dedicated to copyright infringements, costing the music industry upwards of US$29 billion.

Music industry experts say they know that digital services are competing against unlicensed players in markets currently dominated by piracy, but they are aggressively marketing to listeners who they believe are increasingly able and willing to pay for a superior user experience. Marketers are particularly focused on educating young listeners who they think are apt to want to support their music idols and accept that content has a value.

It will in China, if Tencent has its way

Recorded music revenue grew 20.3 percent in China last year, driven by a 30.6 percent rise in streaming, according to IFPI. Tencent Music Entertainment Group dominates with more than 70 percent of China’s streaming market. Through acquisitions last year, it owns China’s three leading streaming services – QQ Music, Kugou and Kuwo. Tencent has 15 million paying subscribers, but while that sounds like a lot, it represents a mere 3 percent of their over 600 million monthly active users.

Free isn’t a sustainable business model so Tencent is aiming to raise its conversion rate of unpaid to paid subscriptions to somewhere between 20 and 30 percent. While they welcomed the government’s digital piracy regulations issued in 2015, they are seeking to displace piracy with a better offer, appealing to an appetite among Chinese music listeners for the higher quality of streaming services. Chinese consumers are also accustomed to paying for things using their mobile phone, which experts say helps combat piracy because it’s harder to steal music on a mobile device than on a PC.

A Tencent ad

A Tencent ad

Circle unbroken

“Will the Circle be Unbroken” is a popular gospel hymn recorded by the Carter Family shortly after the Bristol Sessions that is still sung at the conclusion of every member induction ceremony into the Country Music Hall of Fame. It pays homage and respect to country music’s roots and serves as a reminder of music’s power and legacy.

According to RIAA and the Music Business Association, the music industry today services over 360 music platforms such as Amazon, Deezer, Pandora, TIDAL, and many others, and provides access to 40 million sound recordings globally via digital platforms. Intellectual property licensing accounted for the largest US digital trade surplus among other US services exports (around US$126 billion) and is the largest category of US exports behind travel services.

That’s why the industry looks for every opportunity, including through trade agreements, to remove barriers to digital trade while protecting intellectual property such as the copyrights that support an ever-expanding circle of global music lovers.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).