Published 22 November 2022

As successful as the 12th Ministerial Conference was, the bulk of World Trade Organization (WTO) work lies moribund. But smaller groups of economies are engaging in open and inclusive negotiations — so-called plurilateral processes — which have breathed new life into the organization. These initiatives could show a way forward for the WTO.

Beginning of the era of plurilaterals

When the curtain came down on the 2017 World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, no applause rang through the convention center.

Instead, the audience of trade ministers and senior trade officials from the 164 Members delivered a damning verdict on the December conference and the WTO itself. At most such meetings, the highest decision-making body at the multilateral organization, Ministers have been able to agree on a Ministerial Declaration. In Buenos Aires, the ministers had agreed on nothing.

“We failed to achieve all of our objectives,” then EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom told the Heads of Delegation meeting that closed the conference. “I hope all delegations reflect carefully about the message this sends to our citizens, stakeholders, and our children about the state of the WTO.”

Malmstrom’s sentiment reflected broad and rising concern across the global trading system that the WTO was increasingly inert.

Yet, speaking with reporters afterwards, then-Director-General Roberto Azevedo was anything but forlorn: “This,” he said, “has been a transformational meeting.

Azevedo saw something others had missed. He knew that decisions taken by subsets of WTO members in Buenos Aires opened the door to a more effective means of negotiating trade agreements. The approach was very much designed to blunt ongoing efforts from a handful of WTO members to deadlock issues important to the rest of the membership.

Because the 164-member body operates on the consensus principle — a requirement designed initially to build a common interest into its decision-making — even one member can upend multilateral agreements among the balance of the membership. But WTO rules permit smaller groups of Members, otherwise known as plurilaterals, to pursue their objectives, provided the benefits arising from any agreements reached are extended to all WTO members.

In Buenos Aires, many governments decided they would advance the WTO agenda through open, inclusive, and ambitious plurilateral negotiations and discussions on issues including e-commerce, investment facilitation, women’s economic empowerment, and helping smaller businesses participate in trade. The trend caught on. A few months later, on the margins of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) ministerial meeting, a group of OECD members launched similar negotiations in domestic regulation in services.

Are plurilaterals the future of WTO?

Now, five years later, the bulk of the traditional WTO work plan, including efforts to negotiate new market access commitments in goods, services, and agriculture, and to slash trade-distorting farm subsidies, lies moribund. Yet work by the plurilaterals has progressed briskly. WTO members have already agreed to a deal on services domestic regulation, and guidelines for assisting smaller companies. Important progress has been made on e-commerce, investment facilitation, and women’s issues.

Newly launched discussions on environment are not yet at the negotiating stage but these plurilateral fora offer a valuable space for nurturing critically important discussions like climate change, the circular economy, plastics pollution, and reducing barriers to trade for environmental goods.

These plurilaterals also offer a platform for introducing progressive clauses on social issues. A clause in the 2021 agreement among 67 WTO Members on domestic regulation in services, for instance, states plainly that no new regulations which discriminate against women may be introduced by any of the parties to the pact.

Plurilaterals are not new to the WTO or to its predecessor General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Article V of the General Agreement on Trade in Services and Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs enables subsets of members to engage in agreements that do not involve the entire membership. The groundwork for plurilateral activity was laid in 1947 when the Havana Charter establishing the GATT was signed.

Notable deals with plurilateral origins include the Government Procurement Agreement, which has its roots in the Tokyo Round of the GATT. It was signed in 1979 and became part of the WTO in 1994. The agreement has 21 signatories covering 48 members (the EU counts as one party but all 27 EU member states are also WTO members) and sets the rules on international competition in some US$1.7 trillion in government procurement contracts every year. The agreement was expanded in 2011 and 11 additional members are in the queue to join the accord.

The 1997 Information Technology Agreement encompasses 82 WTO members and covers trade worth US$1.6 trillion annually or about 97% of total trade in those products. The ITA accord was upgraded in 2015 to include 201 additional products worth US$1.3 trillion. This agreement includes 53 WTO members and covers approximately 90% of world trade in those products.

But the plurilateral processes or “Joint Statement Initiatives” born in Buenos Aires differ from these earlier efforts in that they arose from growing frustration after years in which a handful of countries stymied multilateral work.

Opposition faced

India and South Africa object strongly to the plurilateral tack. They say these efforts deflect attention and drain energy from multilateral business including from multilateral negotiations on services, domestic regulation, and e-commerce. The WTO’s ruling General Council has even challenged the legality of plurilateral negotiations. The opposition to plurilaterals runs so strongly that these WTO Members initially sought to prohibit documents or news items pertaining to plurilateral negotiations from appearing on the WTO’s public website.

Roughly three-quarters of WTO Members participate in one plurilateral process or another. Proponents generally agree that plurilaterals are nothing new and that they inject life into a troubled organization. They point out that any outcomes will be implemented in a manner consistent with the WTO’s Most Favored Nation principle and that the meetings are transparent and open to all WTO members. The proponents say that if discussions on these topics don’t take place in the WTO, they will take place somewhere else in a forum where their opponents might not be present and where they would be excluded from any agreements reached.

It is by no means clear that India and South Africa are on solid legal footing with their objections. Moreover, as the US continues to block appointments to the body’s top court, dispute settlement in the WTO is hamstrung by an inoperative appeals system. It is not clear what procedural path opponents might follow to derail the plurilaterals. Given the success of the plurilaterals, and the growing number of members who are joining them, it seems far more likely that opponents will have to adapt to the changing negotiating landscape.

Work on the plurilaterals continues apace with more agreements expected this year and next. This work has accelerated on many fronts and has expanded to new topics. Below is a snapshot that offers detail of some of the most significant plurilateral negotiations in the WTO today.

Ongoing plurilateral negotiations

E-commerce

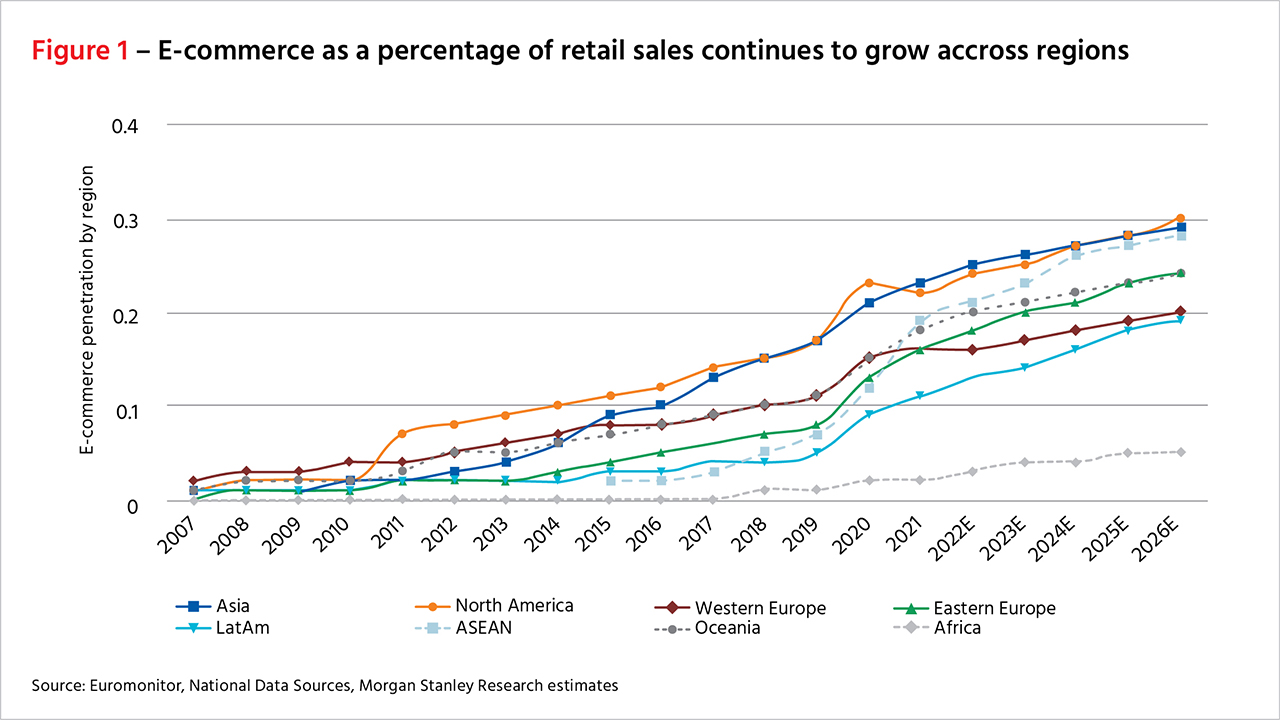

Of all the Joint Statement Initiatives negotiations (JSI) currently underway, the talks on e-commerce are the most closely watched. Given that the volume of e-commerce retail sales amounted to US$5.2 trillion in 2021, according to Statista, and that the figure is projected to grow by 56% to US$8.1 trillion by 2026, it’s easy to understand why businesses are so interested. Morgan Stanley estimates that e-commerce activity now amounts to 22% of global retail sales.

Multilateral work on e-commerce began at the second Ministerial Conference held in Geneva in 1998 — meaning that conventional modes of discussion have not succeeded in reaching a conclusion in more than two decades. At that time, ministers agreed that work on e-commerce would take place across four WTO councils and committees, the Goods Council, the Services Council, the Trade Related Intellectual Property Council, and the Development Committee. Ministers also agreed at that time on a temporary moratorium on the application of import duties on e-commerce transmissions. This moratorium has been rolled over at every Ministerial Conference since but there is the very real possibility that it will expire at the end of March 2024. India, Indonesia, and South Africa have been among the most prominent opponents of the moratorium’s extension.

A decision by the General Council in 1998 extended to the Council the authority to examine cross-cutting issues and to continuously review progress in the four other councils and committees. Quite soon after work commenced, it became apparent that the scope of global e-commerce activity did not lend itself to the fragmented work program agreed to by Ministers. The General Council chair then chose an ambassador to organize a more coherent approach. But in October 2016, this method was terminated when South Africa objected to the direction the group was going. Specifically, Pretoria worried that the group was inching toward negotiating new global rules in e-commerce. This action was a major catalyst to the launching of the plurilateral e-commerce negotiations in Buenos Aires.

Under the stewardship of the ambassadors of Australia, Japan, and Singapore (the so-called co-convenors), 87 WTO Members participate in the e-commerce plurilateral negotiations. They have largely agreed to texts on eight important topics which include:

- Consumer protection

- Spam

- Open government data

- Transparency

- E-authentication

- E-signatures

- E-contracts

- Paperless trading

By the end of the year, these members hope to agree on three further texts including:

- E-invoicing

- Electronic transactions frameworks

- Open internet access

The objective then is to accelerate work with an eye towards striking an overall deal by the end of 2023. This may prove a tall order because little progress has been made in reaching agreements on the critically important issues of cross border data flows, data localization, and the forced transfer of codes and other technologies.

One element that might sweeten a smaller deal would be if the 87 parties to the plurilateral agreed to make permanent the temporary moratorium on application of duties on e-commerce. While this would fall short of a multilaterally agreed upon permanent moratorium it would, if all parties agreed, be a deal covering 90% of the world’s e-commerce trade. This would be easier than agreeing multilaterally to a permanent moratorium, but it would be no sure thing given that some of the e-commerce JSI participants — notably Indonesia — do not now accept a permanent moratorium.

The negotiations on extending, or making permanent, the moratorium will be among the most heated before WTO members during the next year and a half. What Indonesia, India, and South Africa want is more clarity on the scope and definition of e-commerce. They also believe they may have foregone potential tax revenues by not applying duties, and they want the “policy space” to apply duties in the future.

Investment facilitation

Much like the e-commerce negotiations, the negotiations on investment facilitation were borne out of the frustration of many members at not being able to discuss investment-related issues in important WTO meetings.

The flashpoint on investment facilitation occurred in 2016, when the Indian ambassador blocked adoption of the agenda for the General Council after Argentina sought to include the issue. Investment, the Indian ambassador argued, is not part of the WTO’s purview and should not be taken up in the General Council. The response of the Argentines and their supporters was to successfully push for the launch of a plurilateral on investment in Buenos Aires.

These negotiations focus on improving the transparency of regulations linked to foreign investment, removing red tape, technical assistance, and capacity building for developing countries. Importantly the negotiations do not involve investor protection, investor-state dispute settlement, or market access commitments.

Today, 112 WTO members participate in text-based discussions on investment facilitation and are seeking to reach an agreement by the end of this year. The issues that remain to be resolved include how to apply the principle of non-discrimination on taxation and national security exceptions, the extent to which government procurement would be exempted from the agreement, and the legal definition of authorization. Issues regarding transfers and payments are also still on the table.

Nothing comes easily at the WTO. At their September meeting, participants in the investment facilitation JSI expressed their determination and confidence that a deal could be reached by the end of the year.

Domestic regulation in services

The most successful work to date on the JSI came in Domestic Regulation in Services. Negotiators from 67 WTO Members reached a deal in December 2021 to streamline domestic regulation requirements in the services sector and establish rules for licenses and operations.

Micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises

The objectives of this working group are different from those of e-commerce and investment facilitation. The goal in the MSMEs working group was never to negotiate binding rules but rather to develop guidelines helpful to MSMEs seeking to engage more effectively in international trade.

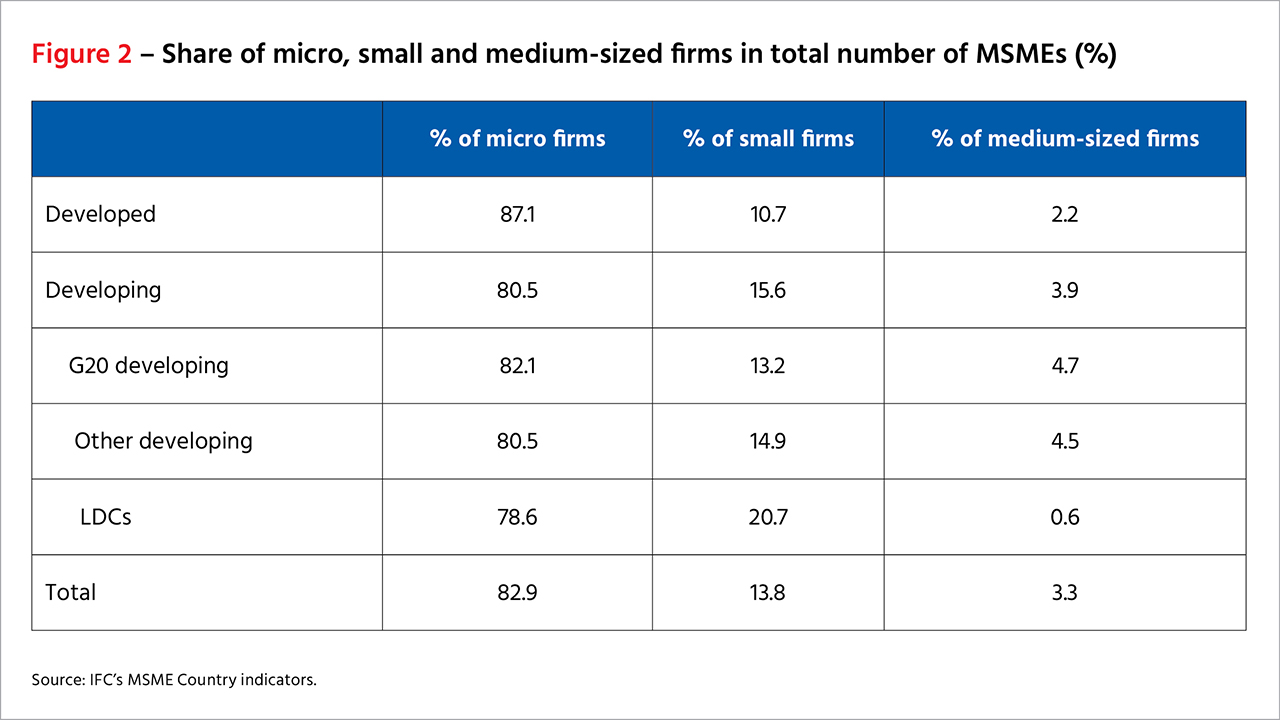

Although some members object to the plurilateral nature of the group’s work, there is no objection on the importance of MSMEs. There is also an appreciation that such companies constitute 95% of all enterprises and 60% of all employment globally. The WTO’s 2016 World Trade Report highlights the opportunities that could arise from more seamlessly integrating MSMEs into global trade. According to the report, in developed countries, companies with fewer than 250 employees account for 78% of exporters but only 34% of exports. In those same countries, MSME's exports amount to only 7.6% of total sales in the manufacturing sector, compared with 14.1% for large manufacturing enterprises.

In Buenos Aires, 88 WTO members agreed to explore ways they could better support the participation of MSMEs in global trade of MSMEs. By December 2020, 97 members reached a deal on a package of MSME friendly recommendations improving access to information, trade facilitation, regulatory development, access to finance, and cross border payments.

Women’s economic empowerment

Like the MSMEs working group, the work in the WTO on women’s economic empowerment is more about raising awareness, establishing guidelines, and helping women participate in international trade, than about negotiating binding rules.

At Buenos Aires, 121 WTO members and observers supported the Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment, which seeks to remove barriers to and foster women’s economic empowerment.

While the Working Group on Trade and Gender has been an effective forum for raising key issues on women and trade, the divide over plurilaterals extends to this group as well. No multilaterally agreed statement was produced at MC12 but in the outcome document, ministers agreed on “women's economic empowerment and the contribution of MSMEs to inclusive and sustainable economic growth.” The WTO therefore only agreed to “take note” of the work that has been done on women’s participation in trade.

Conclusion

Multilateral outcomes will always be the goal of WTO members. Such results are more efficient and more effective. Indeed, in many WTO spheres — subsidies, intellectual property, anti-dumping — plurilateral outcomes are not feasible. Moreover, partial deals brokered at the Geneva Ministerial Conference in June on fisheries subsidies, patent protections for vaccines, and food security underscore that multilateral successes are attainable even now.

Yet as successful as MC12 was, a great deal of work was left unfinished. The immense difficulty in achieving its results underscores the monumental challenge the organization faces in trying to jumpstart long paralyzed talks in the multilateral format.

In taking a pragmatic and results-oriented approach to their work, participants in the JSIs have breathed new life into WTO negotiations. The dynamism evident in the plurilateral groups stands in stark contrast to the flatlining progress in talks on industrial tariffs, intellectual property protections expansion, agriculture subsidies, and services market access.

The progress seen in the JSI has been a consistent bright spot for those who believe that for the WTO to remain relevant, it must have skin in the game on urgent global issues from climate change to women’s participation in trade. With two agreements already reached, on domestic regulation in services and MSMEs guidelines, and the prospect of an accord in investment facilitation, there is every reason to believe that plurilateral work in the WTO will accelerate and expand.

For the WTO to flourish in the multi-crisis environment of today it needs every tool at its disposal. Plurilaterals were a creative response by like-minded WTO member subsets to the deepening deadlock in negotiations in Geneva. So far at least, these initiatives have lit a way forward and they hold the promise of significant results in the future.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).