Published 16 August 2022

After years of sharp tariff rises in some countries, and their elimination or reduction in others with new and existing bilateral and regional trade agreements, firms are now being hit by one of the most volatile currency environments in recent memory.

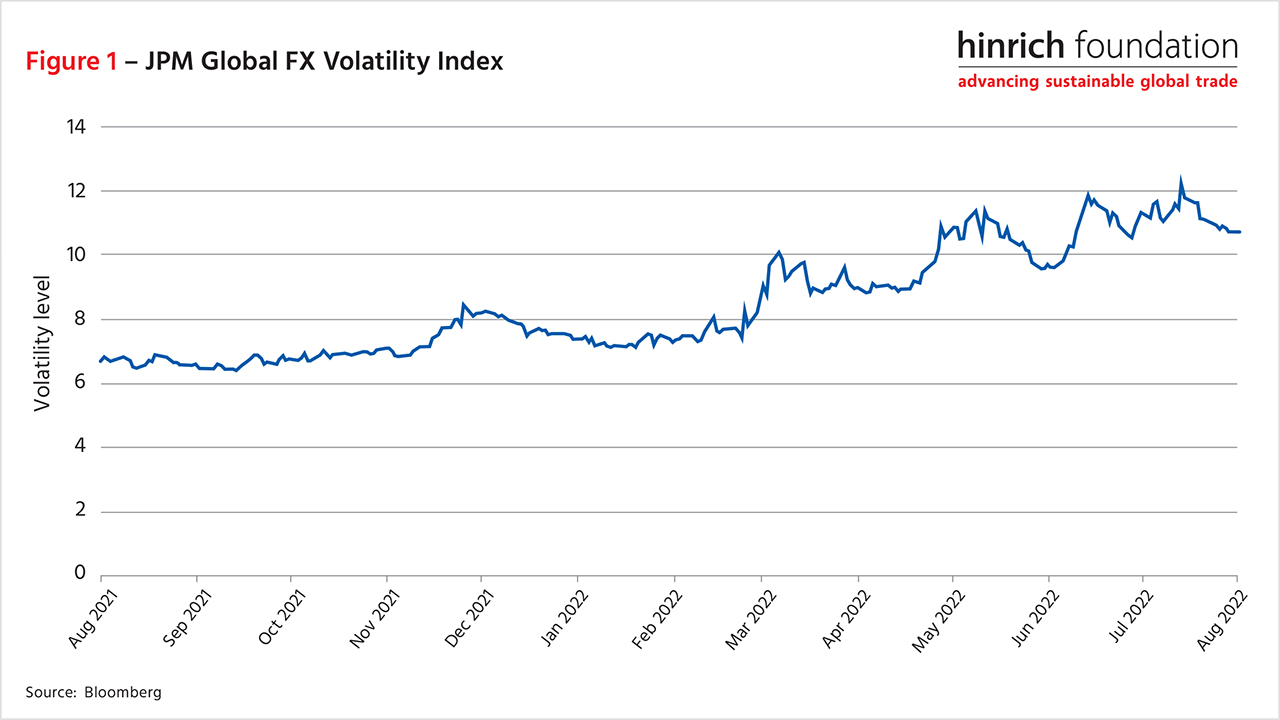

The JP Morgan Chase Global FX Volatility Index, a leading measure of currency movements, has risen by nearly 66% in the year to July.

A confluence of factors have led us to this point, including but not limited to: supply chain bottlenecks and rising shipping costs which have fed an inflationary environment as demand for goods returns in regions that are opening up after the pandemic; geopolitical uncertainty caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, along with growing concerns that China may now be emboldened to take action on Taiwan; and an economic slowdown in China itself, which has, arguably, been self-inflicted by draconian zero-Covid policies. Mismatches in supply and demand between currencies, along with the flight to safety amid geopolitical and global macroeconomic uncertainty, tend to create greater exchange rate volatility.

Now, following a prolonged period of extremely loose monetary policy, central banks the world over – with the notable exception, so far, of the Bank of Japan – have followed the US Federal Reserve into a tightening cycle, some faster than others. The Fed’s most recent rate hike of 75 basis points was the second consecutive rise of that magnitude. The first, in June, was already its largest move since 1994. The Bank of Canada went one step further, raising its lending rate by a full percentage, the largest single move it has ever taken. The European Central Bank’s 0.5% increase, dovish by comparison, nevertheless still came as a surprise to many watchers.

Some have even gone so far as to describe current conditions as a “reverse currency war,” as countries aggressively hike rates to counter increasingly expensive and inflationary imports resulting from the strengthening dollar – the antithesis of competitive devaluations.[1] At a time when global supply chains are already being roiled by shocks such as the diminution of the WTO, tense US-China relations, and the hangover from Trump-era trade policies, the added effects of currency volatility may force some hard decisions on executives in the short term.

Now it’s a problem…

The US dollar dominates invoicing in global trade transactions, accounting for between 70% to 95% of the total outside the Eurozone[2] despite China’s rise and efforts to diversify the global slate of reserve currencies.

John Connelly, then the US Treasury Secretary, once famously described the US dollar as “our currency but your problem” at a 1971 meeting of the G-10 after the Nixon administration took the dollar off the gold standard, among a host of other measures that helped to break the post-war Bretton Woods system.[3]

At the moment, it appears to be a problem for the US, too, at least for its exporters and multinational corporations. Whether its strength will actually temper inflation is another matter. Companies across all sectors are already warning of the impact of overseas earnings repatriated in currencies fast weakening against the greenback. And the hits have been substantial – amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars in losses to date for individual companies and up to US$40 billion in total.[4]

A major question is if the Fed is inadvertently accomplishing something Trump’s tariffs could not: reshoring production. Supply chains are harder to move than policy discussions often assume. It’s an over-simplification, but whereas a garment manufacturer really only needs to find building space and move around sewing machines, for example, it’s far more difficult for a producer of higher value-added goods, with hundreds of components, to shift its supply chains, especially when there are only a handful of reliable suppliers to begin with. Many firms in the automotive and tech sectors learned this the hard way in 2011 in the wake of the triple disaster in Japan and later when severe floods disrupted production in Thailand.

Other considerations are also involved. One of the outcomes the Fed is trying to prevent is the US entering a wage-price spiral, which would make the US all the more unattractive to firms considering re-shoring. Another is that even if the Biden administration does finally get around to easing the tariffs imposed by its predecessor, or lifting them altogether, the movement of currency pairs can render those tariffs a non-factor anyway. Finally, forecasting currencies becomes harder the farther out you look except in the few cases where one of the currencies in question is pegged to the dollar, de facto or otherwise, making it difficult to factor into investment decisions.

For Asia’s suppliers, a mixed blessing

Central banks in the developed world are not the only ones chasing the Fed. After holding back, perhaps longer than they should have, monetary authorities in Asia are now following suit, albeit at a slower pace.[5] India, the Philippines, Malaysia and others in the region have all raised lending rates in recent months, with Indonesia being the main holdout so far.

For the hundreds of thousands of smaller enterprises in the region that export finished products and intermediate goods that go into the supply chains of multinationals, rising interest rates and currency volatility present a mixed blessing.

Such companies often lack the resources to evolve sophisticated currency hedges against currency fluctuations. But they have been able to count on a boon of sorts: Some of their customers have been resorting to early payments, counting on getting a slight discount from contractual terms if they post early-bird dues. This helps smooth out the working capital cycle for the small and mid-size enterprises, allaying an otherwise constant concern, and allows them to earn greater interest on cash deposits after more than a decade of low interest rates.

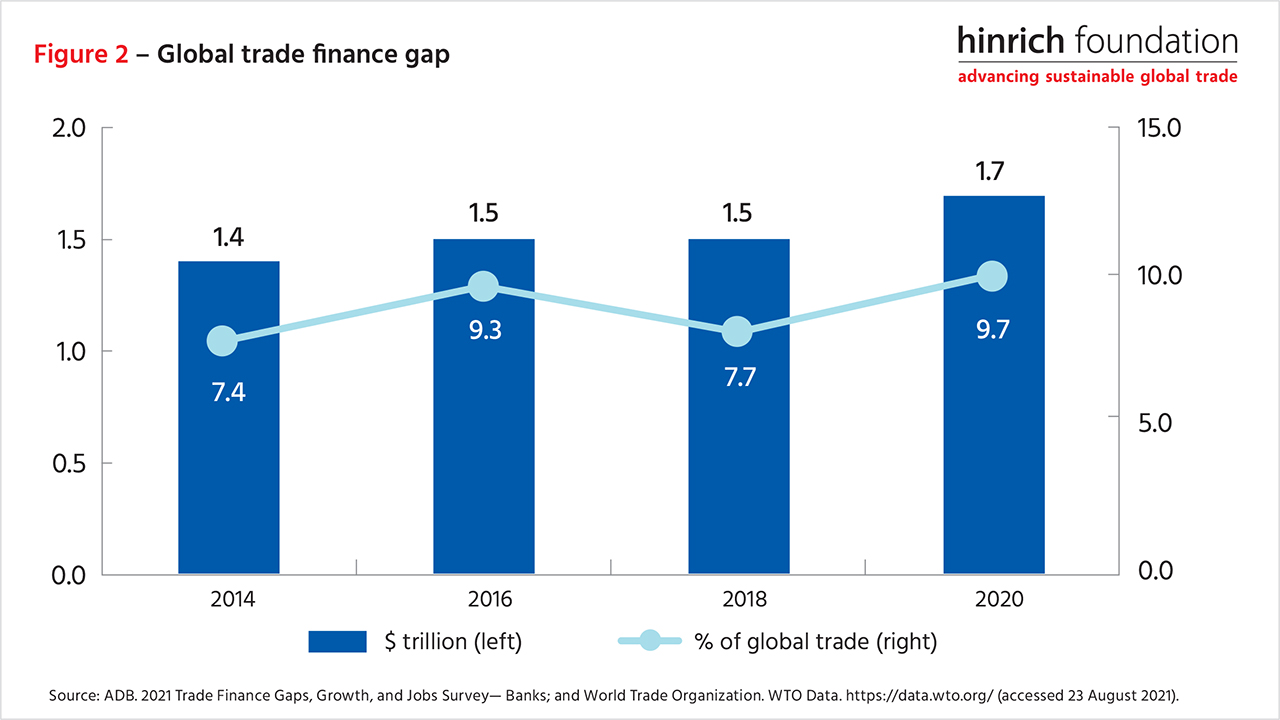

However, higher borrowing costs are likely to further reduce the availability of trade finance, a vital but oft-overlooked aspect of global trade. The latest available estimate from the Asian Development Bank, which it has been producing every two years since 2014, is that there was a US$1.7 trillion gap between the supply and demand of trade finance in 2020, a 15% increase over 2018.[6]

Small and medium firms accounted for 40% of rejected trade finance applications, the ADB found in its survey. Banks surveyed for the same report cited risks related to SME balance sheets and macroeconomic conditions arising from the pandemic as their main reasons for rejecting applications. If buyers do indeed increase their willingness to pay ahead of schedule, that should ameliorate balance sheet risks. But macroeconomic risks being what they are now, and with returns on safer assets rising, the result could be a continuation of current trends, all else being equal.

China looms over longer-term outlook

Often lost among the analysis of China’s ascent in the structure of global supply chains is the stability of its currency. To be sure, its accession to the WTO in 2001, and the improved market access it received in return, its large population, and low cost of labor were also instrumental. But its persistence in largely maintaining the value of the renminbi against the dollar in a tight band provided foreign buyers and investors with a level of stability unrivaled elsewhere.

Now, as the macro effects of US monetary tightening, the Ukraine war, and China’s own Covid lockdowns converge, the renminbi has come under sharp pressure against the dollar. Though the Chinese currency has regained ground in recent weeks, its weakness dragged down other emerging market currencies, not just in nearby Asia but including those as far afield as commodity exporters Brazil and South Africa. The implications for supply chain managers are far reaching. Potentially enough so that once-sticky supply chains could swiftly become unstuck.

***

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/d189b2f2-808a-4a9b-a856-234181f98c2f#10495900

[2] https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-u-s-dollar-20211006.htm

[3] https://www.ipe.com/the-dollar-is-our-currency-but-its-your-problem/25599.article

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/189a161c-7247-431d-83fa-f7645ee22573

[5] https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/asias-central-banks-forced-play-catch-up-global-rush-raise-rates-2022-07-20/

[6] https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/739286/adb-brief-192-trade-finance-gaps-jobs-survey.pdf

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).