Published 20 September 2019

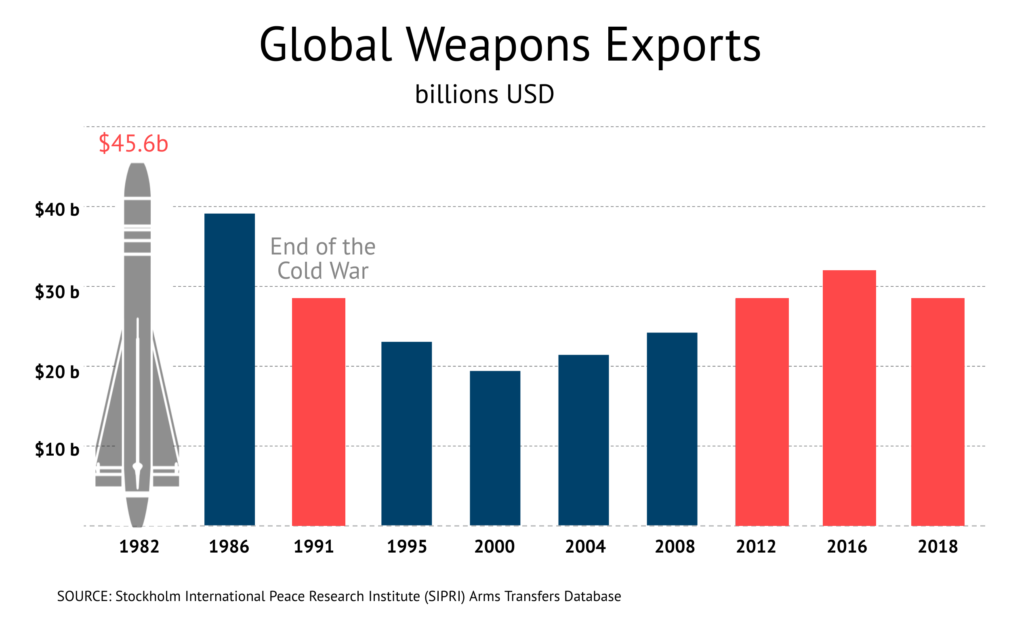

After a decade of steady increase, the volume of arms trade by 2012 had reached levels not seen since the end of the Cold War.

Hotter since the Cold War

For obvious reasons, trade in arms is not governed by the same global trade rules as selling a doggy snood on Etsy. The rules of engagement are different and global flows of arms tell stories not of lighthearted fashion trends but of the enduring reality of global conflicts, the escalating and diffusing of tensions – the arming and disarming that reflects the current and projected state of international security.

Governments, formal military alliances and international organizations procure and sell arms for defense, for peacekeeping operations, and to engage in conflict. Conflicts today routinely intertwine regular military forces, militias and armed civilians. After a decade of steady increase, the volume of arms trade by 2012 had reached levels not seen since the end of the Cold War.

Up in arms

2018 saw the continuation of armed conflicts throughout the Middle East and North Africa in Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen. In sub-Saharan Africa, armed conflict raged in 11 countries including Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Afghanistan remains among the world’s most lethal states after decades of fighting.

India and Pakistan, Myanmar and other countries in Southeast Asia experienced armed conflict throughout the year and Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine remains unresolved. Colombia’s peace process hit rough patches, armed gangs threaten security in Central America, and Venezuela remains turbulent. This list is long, incomplete, and in flux, fueling demand for arms in conflict areas. At the same time, some 60 multilateral peace operations were active in 2018.

For 50 years, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) has gathered original data on world military expenditure and international arms transfers, analyzing trends in conflict, arms production and arms controls. In all, SIPRI estimates global military expenditure at US$1.8 trillion and puts the total value of the global arms trade in 2017 at some US$95 billion with weapons exports valued around US$27.6 billion.

Arms transfers between 2009 and 2013 were 23 percent higher than in the period between 2004 and 2008. In the period 2014-2018, arms transfers reached the highest level since the end of the Cold War.

Who sells and who buys in the war economy

Official reporting is scant. Government to government transfers occur through varying types of complex and opaque arrangements. Pinning down numbers is also complicated by the existence of covert trade in arms. Within the realm of what SIPRI can track, the market is dominated jointly by the United States and Russia. According to SIPRI’s numbers, 202 states, 48 non-state armed groups, and five international organizations received arms shipments sometime in the last five years.

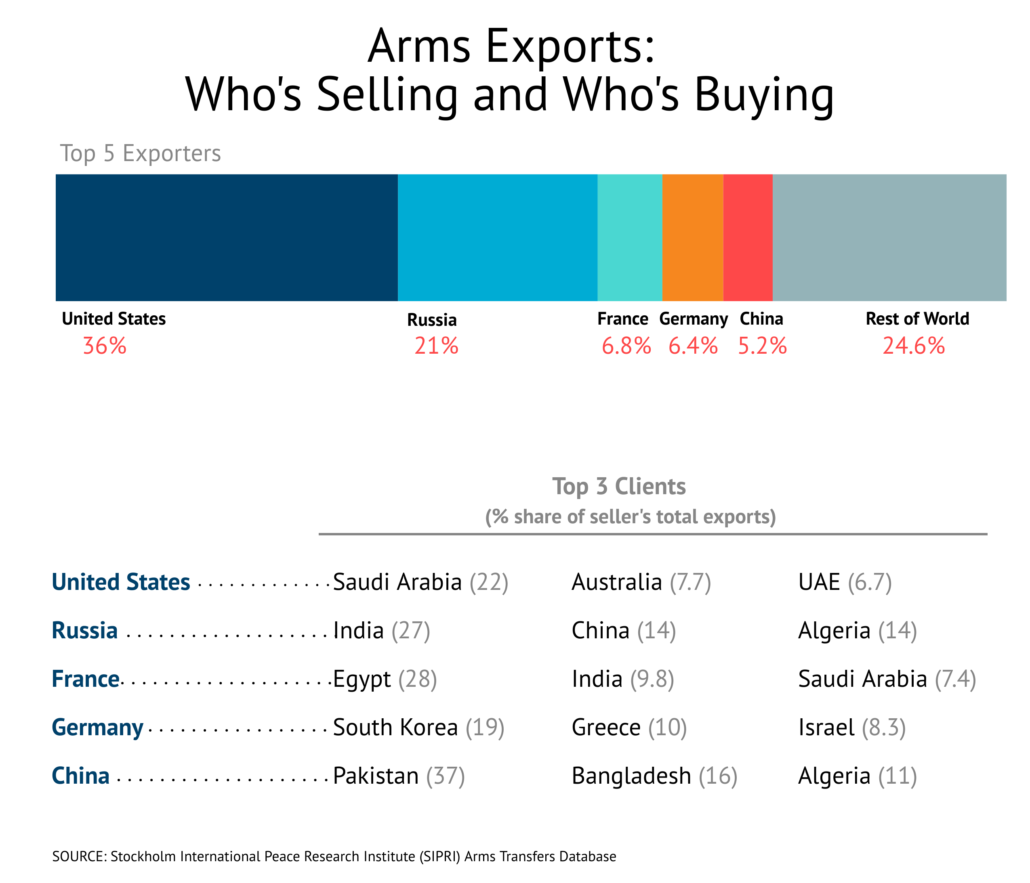

The United States, Russia, France, Germany and China are the five largest exporters of major arms, accounting for 75 percent of all arms exports, but SIPRI has identified as many as 67 countries that exported major arms in the last five years. The United States and Russia together comprise 57 percent of the total. The five largest importers were Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, Australia and Algeria, together accounting for 35 percent of total arms imports between 2014 and 2018. The political alignments can be seen by matching the buyers and sellers.

Notably, advanced combat aircraft accounted for more than half of all US major arms exports over the last five years and will remain the main driver with nearly 900 orders in the pipeline. Guided missiles accounted for 19 percent of US major arms exports and the United States is the primary exporter of ballistic missile defense systems.

Russia’s exports declined over the last five years as sales to India and Venezuela dropped by 42 percent and 96 percent respectively. Over the same period, Russia’s sales to the Middle East increased 19 percent, mainly to Egypt and Iraq. SIPRI reports that China supplies relatively small volumes of major arms spread across 53 countries, up from 41 five years ago. At the same time, China is the world’s sixth largest importer of arms. Russia supplied 70 percent of China’s arms imports over the last five years.

Under control

Seven of the world’s largest defense companies by arms sales are American. They include Lockheed Martin with international arms sales worth US$40.8 billion in 2016, and Boeing at a distant second with US$29.5 billion in sales. Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics come in the next tier with sales between US$19 and US$23 billion. Among the top 100 firms, US companies accounted for 58 percent of total global arms sales in 2016.

When it comes to production and trade in military supplies, the WTO steps out of the way. Article XXI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade provides a national security exemption:

“…nothing in this Agreement shall be construed…to prevent any contracting party from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of essential national security interests…relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment.”

Trade in conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies (those with both military and commercial applications) is regulated through other policies that include government defense procurement regulations, national export control licensing regimes and embargoes. In the United States, under the Arms Export Control Act and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, exports of defense materials and services by US firms are tightly controlled through licensing approvals.

Wassenaar Arrangement

Forty-two member countries maintain national export controls in conformance with items included on the 1996 Wassenaar Arrangement’s two control lists. As part of the Arrangement, members also agree to voluntarily and confidentially exchange information about transfers to non-Wassenaar countries of conventional weapons and dual-use goods and technologies on these lists. Weapon categories to be reported include armored combat vehicles, large-caliber artillery, military aircraft, missile systems, small arms and light weapons.

Wassenaar members are encouraged to use non-binding criteria to help determine whether potential arms exports could lead to “destabilizing accumulations,” and to guide their disposal of surplus military equipment. Wassenaar and other efforts to restrain arms transfers through international treaties and multilateral embargoes suffer, however, from low levels of national government engagement by important producers and importers of weapons.

Military-industrial complex-ity

Governments seek to procure technologically advanced weaponry for their own national security. At the same time, they must prevent the sale of such weapons to others who would use them against the state or who would deploy them to fuel conflicts that run counter to national security interests.

In balancing these objectives, national export control regimes have struggled against the pace of technological innovation and the proliferation of technologies that have dual commercial and military applications. The defense industry itself is defined by this paradox – it is propelled forward by government protected from competition but also shaped by market forces that induce innovation, specialization and consolidation.

As the costs and complexity of developing and manufacturing advanced weapons increase, firms specialize in facets of production. Interdependence among firms has deepened as global supply chains tend to be anchored by a handful of large tier-one firms. The industry has consolidated, including by merging across borders. In circular fashion, these developments make it harder for governments to regulate foreign investment and maintain appropriate controls on arms transfers.

Adding the complexity of this unique industry, firms that enjoy a special status under trade rules for military production also have commercial products and sales for which the normal rules apply. It’s a heavy invisible hand in the market for arms. Global trade rules need not apply.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).