How to use it

Industrial Policy and International Competition: Trade and Investment Perspectives

Published 30 August 2022

The pandemic strengthened the state’s role in many economies. This white paper from the World Economic Forum (WEF) presents a useful discussion of the impact of industrial policies on international competition. It also provides recommendations for governments to consider as they formulate international trade rules governing the use of industrial policies.

Here’s how to use the white paper entitled Industrial Policy and International Competition: Trade and Investment Perspectives.

Why the report matters

Subsidies and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), have been used for decades by governments to support economic growth. Yet the disruptions of recent years have prompted even those that largely supported laissez-faire economics to turn to industrial policy. Supply chain disruptions caused countries to reconsider where supplies are located and how to make them more resilient.. Increasing US-China contention has led to greater focus globally on China’s use of subsidies, and in particular, which forms of subsidies affect fair competition.

The paper provides a useful summary of key rules and concerns related to the most commonly adopted industrial policy measures, along with a summary of issues to be addressed when regulating these policies.

What’s in the report

The report contains two key sections:

- An analysis of the key instruments of industrial policy, the international rules governing their use, and the debates surrounding reform of these instruments, including subsidies, state ownership and control, government procurement, investment screening and controls, and trade remedies; and

- A summary of the key concerns that the WEF recommends considering as industrial policies, and international trade rules governing them, are adopted.

How to find the insights

This report contains key insights on industrial policies, organized according to policy areas of concern to those negotiating international trade rules. We distinguish the insights into the following categories:

Subsidies | State ownership and control | Government procurement | Investment screening and controls | Trade remedies and unilateral actions | Recommendations for improving international trade rules

Subsidies

- The WTO defines subsidies as “financial contributions by governments and public bodies that confer benefits to individuals and firms.” (p. 8)

- Subsidies should be understood in the context of value chains for their role in supporting downstream production when provided to upstream inputs. (p. 8)

- WTO rules place restrictions on subsidies but generally allow them so long as they are not trade-distorting. (Box 1, p. 8)

- A fundamental issue with regulating subsidies is defining “good” and “bad” subsidies. In times of crisis, governments may use subsidies to address legitimate public policy issues and need the space to do so. (p. 10)

- Governments do not routinely report their subsidies, which makes it challenging to identify their economic impact. (p. 10)

- The G7 countries account for the greatest share of subsidies granted. Large emerging markets tend to implement more trade-related investment and price-control measures. (p. 11)

State ownership and control

- Policymakers are concerned that SOEs are increasingly competing with private companies in a way that gives them unfair advantages over competitors and can distort trade and investment. (p. 12)

- SOEs have grown significantly in size and number – they are responsible for 55% of infrastructure investments in emerging and developing countries and their assets amount to $45 trillion. (Figure 3, p. 12)

Extracted from: Industrial Policy and International Competition: Trade and Investment Perspectives by World Economic Forum

Extracted from: Industrial Policy and International Competition: Trade and Investment Perspectives by World Economic Forum

- WTO rules require SOEs to operate on a commercial basis and in a non-discriminatory manner, yet SOEs are often motivated by more than commercial concerns, including national strategic and geopolitical objectives; yet these rules may not adequately take into consideration different kinds of SOEs or the levels of control governments exert over them. (p. 13)

- Key areas of contention are how to define an SOE, how to gauge the level of control a state has over the SOE, and how to judge between behavior and ownership of the entity. International rules have different definitions and requirements for state control. (p. 13)

- The Covid pandemic has led to more state ownership and control of commercial enterprises, concurrent with government aid or bailouts to industries most affected by the pandemic’s economic disruptions. This triggers a debate over how and when governments should exit such investments. (p. 14)

Government procurement

- Governments have long promoted domestic industry through government procurement policies. (p. 14)

- Government procurement is exempted from national treatment obligations of the GATT and GATS agreements unless members are party to the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). (p. 15)

- The US and the EU have recently proposed or adopted new restrictions on government procurement to ensure that more procurement comes from domestic producers, or GPA or regional trade agreement members. (p. 15)

China’s bid to join the GPA raises additional questions about how to treat China’s SOEs. (p. 15-16)

Addressing transparency in procurement could help expand government procurement rules to all WTO members. Common transparency requirements across countries would facilitate participation by suppliers engaged in foreign procurement markets, without the need for market access commitments. (p. 16)

Investment screening and controls

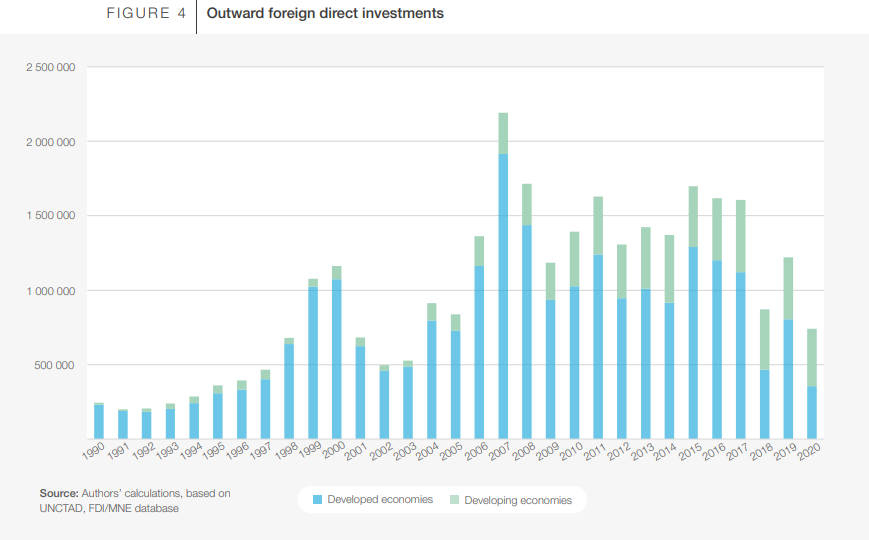

- Over the past two decades, developing economies have become both significant recipients of foreign investment and significant investors. (Figure 4, p. 16)

Extracted from: Industrial Policy and International Competition: Trade and Investment Perspectives by World Economic Forum

- Increased foreign investment, particularly from state-owned entities, has led 31 countries to adopt or reform mechanisms to screen foreign investments. (p. 17)

- Foreign investment screenings raise questions about what constitutes a “national security” interest, and whether these mechanisms are being used as protectionist measures.

- The European Commission has also proposed an investment screening mechanism on the basis of foreign investments benefitting from state subsidization. (p. 17)

Trade remedies and unilateral actions

- Trade remedies protect domestic industry against foreign subsidization, sudden surges in imports, and unfair dumping of low-priced imports. (p. 18)

- Trade remedy investigations rose dramatically in 2020 after a few years of decline, led by new investigations initiated by India and the US. (Figure 5, p. 18)

- Trade remedies are domestic actions taken in accordance with WTO rules. (p. 19)

- In anti-dumping cases, governments distinguish between non-market economies (NMEs) and market economies, which can lead to higher duties assessed on NMEs in anti-dumping actions, and debates over how best to make these assessments. (p. 19)

- A future area of debate is the application of countervailing duties to third countries that have received transnational subsidies from other governments. (p. 19)

Recommendations for improving international trade rules

- Subsidies: Rule-makers should do more to clearly define and list “good” and “bad” subsidies, and the circumstances in which they can be used. Agriculture and defense subsidies in particular should be targeted for reforms. (p. 21)

- State ownership and control: Rule-makers should consider definitions for SOEs that distinguish between ownership and behavior and strive to develop a shared code for corporate governance to help guide SOE behavior. (p. 21)

- Government procurement: Rule-markers should seek to expand GPA membership and coverage, and restart work on a multilateral agreement on transparency in government procurement. (p. 21)

- Investment screening and controls: Rule-makers should strive for more clarity about the definition of national security; how to treat investments by state entities; more clarity, certainty, and transparency about domestic review processes; and address the need and process for judicial review of screening decisions. (p. 21-22)

- Trade remedies: Rule-makers should consider offering China market economy status in exchange for reforms; agree to limits on unilateral actions; and clarify rules countering transnational subsidies. (p. 22)

- Transparency: Rule-makers should incentivize better notification of industrial policy measures; support tracking initiatives and develop technological solutions for better tracking; and increase cross-policy coordination. (p. 22)

Conclusion

This WEF white paper zeroes in on some of the most contentious and difficult issues in international trade today, at a time when governments around the world are reconsidering the role of the state in the economy, and the importance of international institutions like the WTO. By providing clear areas for further work, international focus, and improvement, the WEF makes a positive and useful contribution to this critical debate.

***

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- Subsidies and market access: Towards an inventory of corporate subsidies by China, the EU, and the US

- Industrial subsidies and the pressing need for action

- US and EU look for a deal on subsidies while eyeing China

External Resources

- Enhancing Global Trade Intelligence – Peterson Institute for International Economics

Alan Wm. Wolff makes the case for effective policymaking and business decision making by enhancing global trade intelligence. - An Outbound Investment Screening Regime for the United States? – The Rhodium Group and the National Committee on US-China Relations

On the genesis of the legislation that review US outbound investment to China and other countries of concern. - Special report: Business and the state – The Economist

After a long liberalising era, the state has bounced back. That is not a good thing, argues Jan Piotrowski.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).