Published 23 October 2020

The US-China trade war and Brexit have generated quantifiable uncertainty in the marketplace, but the impact of those events is being eclipsed by the uncertainty generated by the global pandemic.

Taking an economic pulse

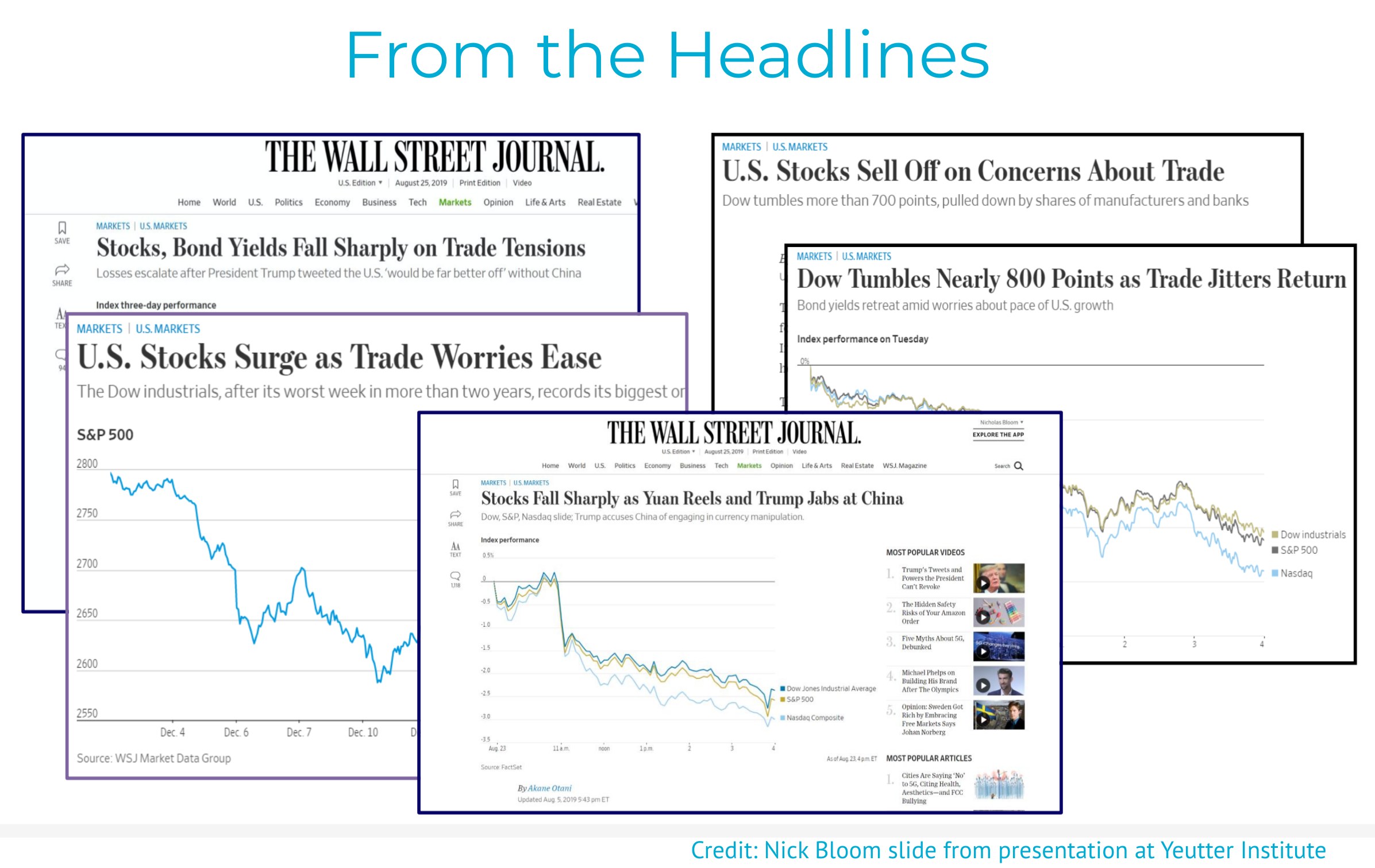

If you search the Internet for the term “economic uncertainty” or close variations, you’d find what you already know just living through the current times. It’s the default word to describe the uptick in political and trade tensions and in the precarious health of the national economy as well as our personal economic lives.

Even prior to COVID-19, the US-China trade war and Brexit — to tick off current major stressors — Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom, along with his colleagues Scott Baker from Northwestern University and Steven Davis of the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, sought to quantify the impact of uncertainty and its impact on business, consumer and policy decisions and vice versa.

Rising levels of political and policy uncertainty are perceived to have a dampening effect on commercial investments, hiring, and economic growth, and appear to be reflected in stock market volatility. Policy uncertainty – including uncertainty in trade policies – doesn’t only manifest as risk aversion by companies, it may effectively raise the cost of capital for investing. Companies may freeze hiring and begin to rely on attrition to thin their employment ranks or begin layoffs in anticipation of slower growth. This behavior in turn may diminish the returns from government stimulus spending, itself designed to induce firm investments by offsetting some of their risk. Stimulus works better if policy and economic uncertainties are reduced.

“Uncertainty” is often described as the intangible or “X factor” in economic forecasts. Bloom and his colleagues wanted to find out whether uncertainty is more tangible and evident than we think.

Stress testing

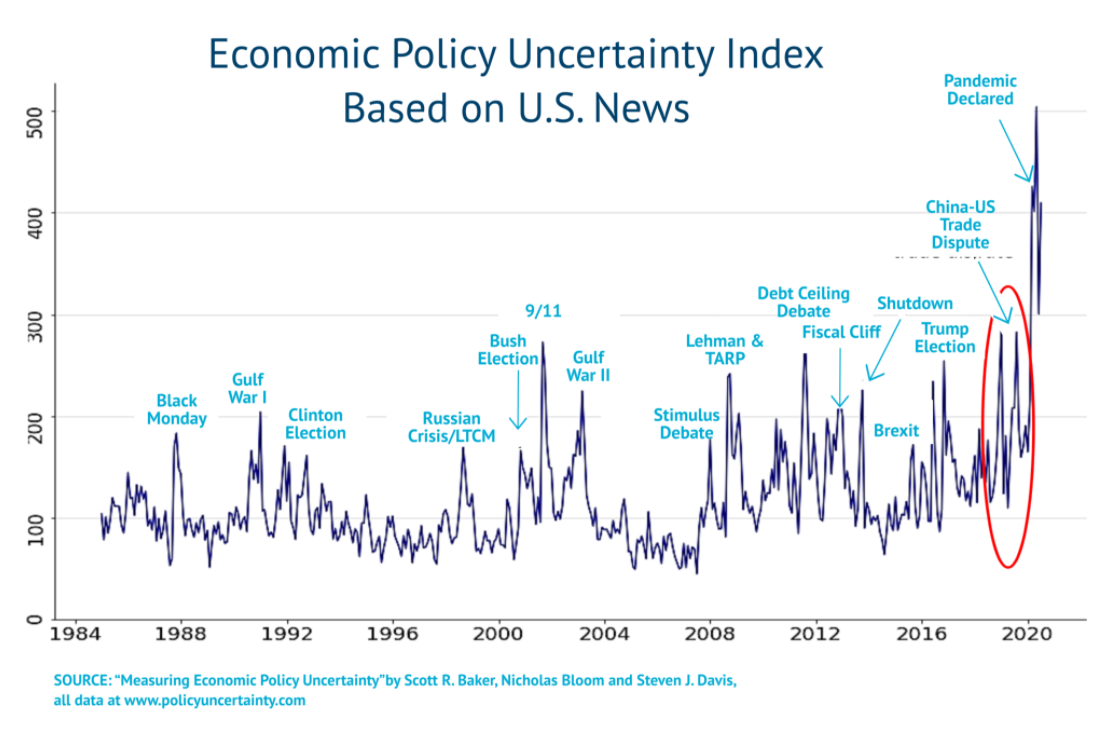

Bloom, Baker and Davis constructed an index to measure policy-related economic uncertainty. They used data from search results from newspaper coverage by 10 large publications including the Miami Herald, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News, looking for mentions of economic uncertainty within certain parameters. Their work included a measure of fiscal uncertainty as represented by the number of federal tax code provisions set to expire in future years and drew on disagreements among economic forecasters as a proxy for uncertainty.

An “echo” report

First, some caveats:

Newspaper coverage is of course dependent upon the reporting choices made by editors at these papers and weighed against what else is driving the news of the day that may eclipse trade policy. The media mirrors uncertainty it observes and may also generate uncertainty through its own reporting.

And while the stock market has shown patterns associated with political elections, the market doesn’t make significant swings in close proximity to political elections. Politicians like to suggest that party majorities across government is good for the markets. But it would appear that political gridlock offers more stability and is considered more “market friendly” than when one political party has both houses of Congress and the White House.

That said, the Economic Policy Uncertainty index (EPU) created by Bloom and his colleagues maps the impact of “uncertainty” such that we can see clear stock market volatility associated with other types of major political events and policy developments – most recently, flare-ups in the US-China trade dispute and the unfolding of Brexit.

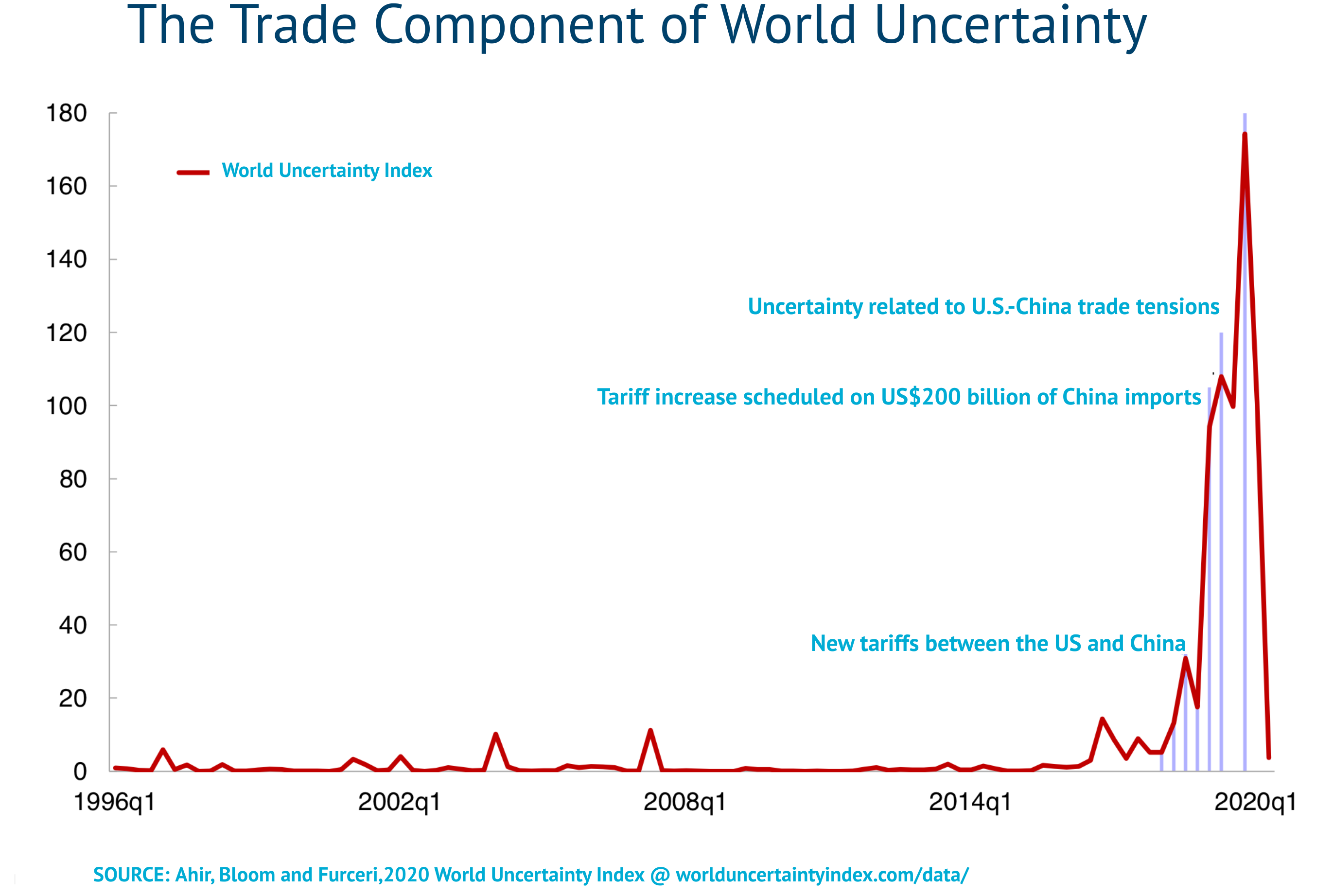

The impacts of uncertainty generated by the global pandemic are clearly much higher than the trade uncertainty associated with the US-China trade war and Brexit.

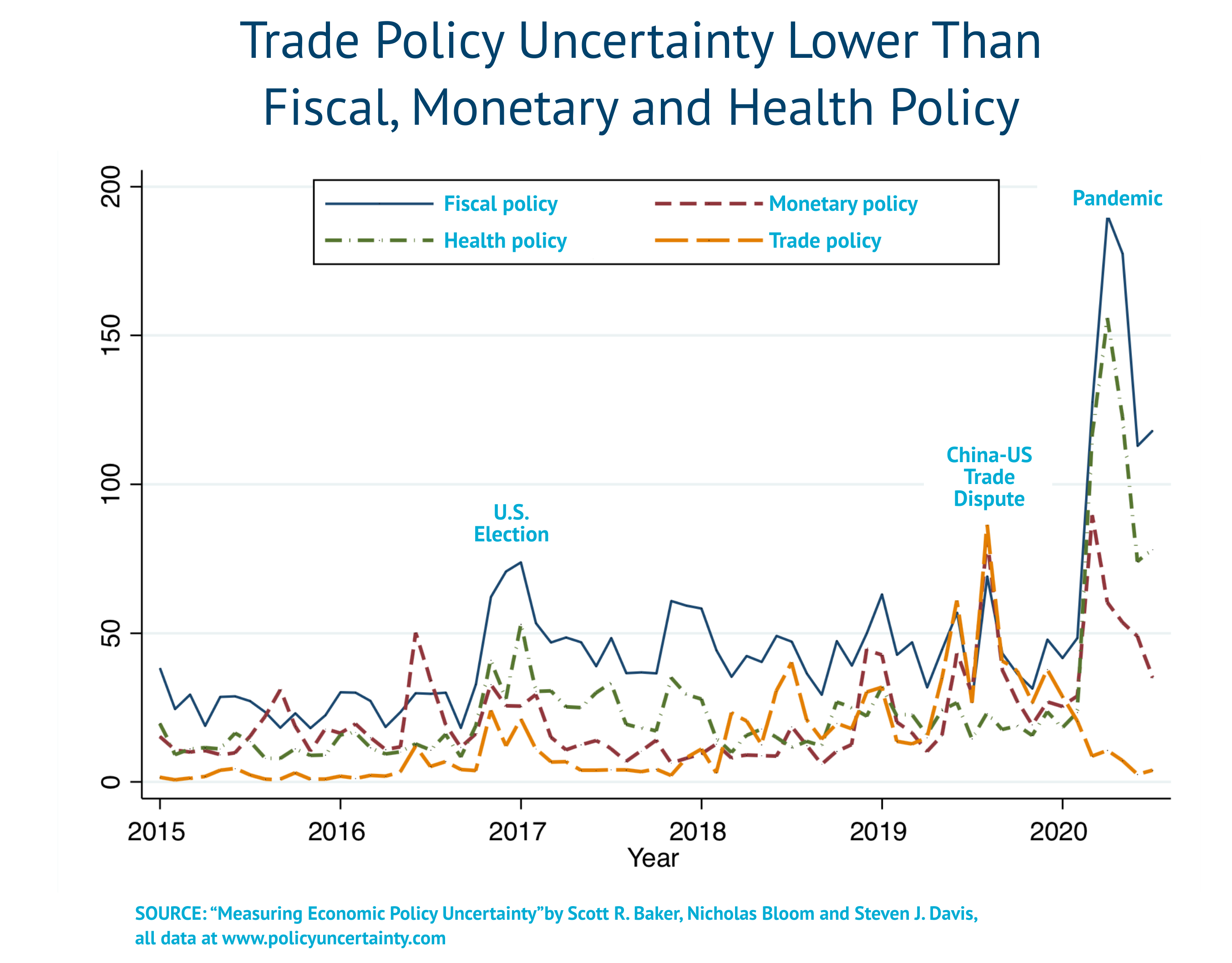

Furthermore, when comparing key words associated with the four different categories of health, fiscal, monetary and trade policy, trade policy uncertainty had been the highest among the four with a spike in 2019, but it is now low and the lowest among these four – again, due to overriding concerns driven by the pandemic.

Bloom has cautioned that trade uncertainty as a driver may have receded in comparison with other concerns. However, the open-ended nature of the current US-China trade conflict and the looming Brexit deadlines mean that trade uncertainty may be more of a sleeping than a slayed giant.

In general, Bloom, Baker and Davis find that, as measured by the EPU index, current levels of economic policy uncertainty are at “extremely elevated levels.” Since 2008, economic policy uncertainty averaged about twice the level of the previous 23 years.

Pile on the social anxiety

Bloom, Baker and Davis have also extracted Twitter data on economic uncertainty and compared their findings with the results reflected in the EPU index. Twitter chatter does reflect much of the same heightened sense of anxiety over the uncertainty of Brexit and US-China trade tensions, but the levels of anxiety generally track lower. This could be largely attributed to the sheer breadth and inconsistency of posts by the millions of people tweeting. It’s hard to find the signal in all that considerable and often frivolous noise.

From 9/11 to SARS to El Niño: An entire world of uncertainty

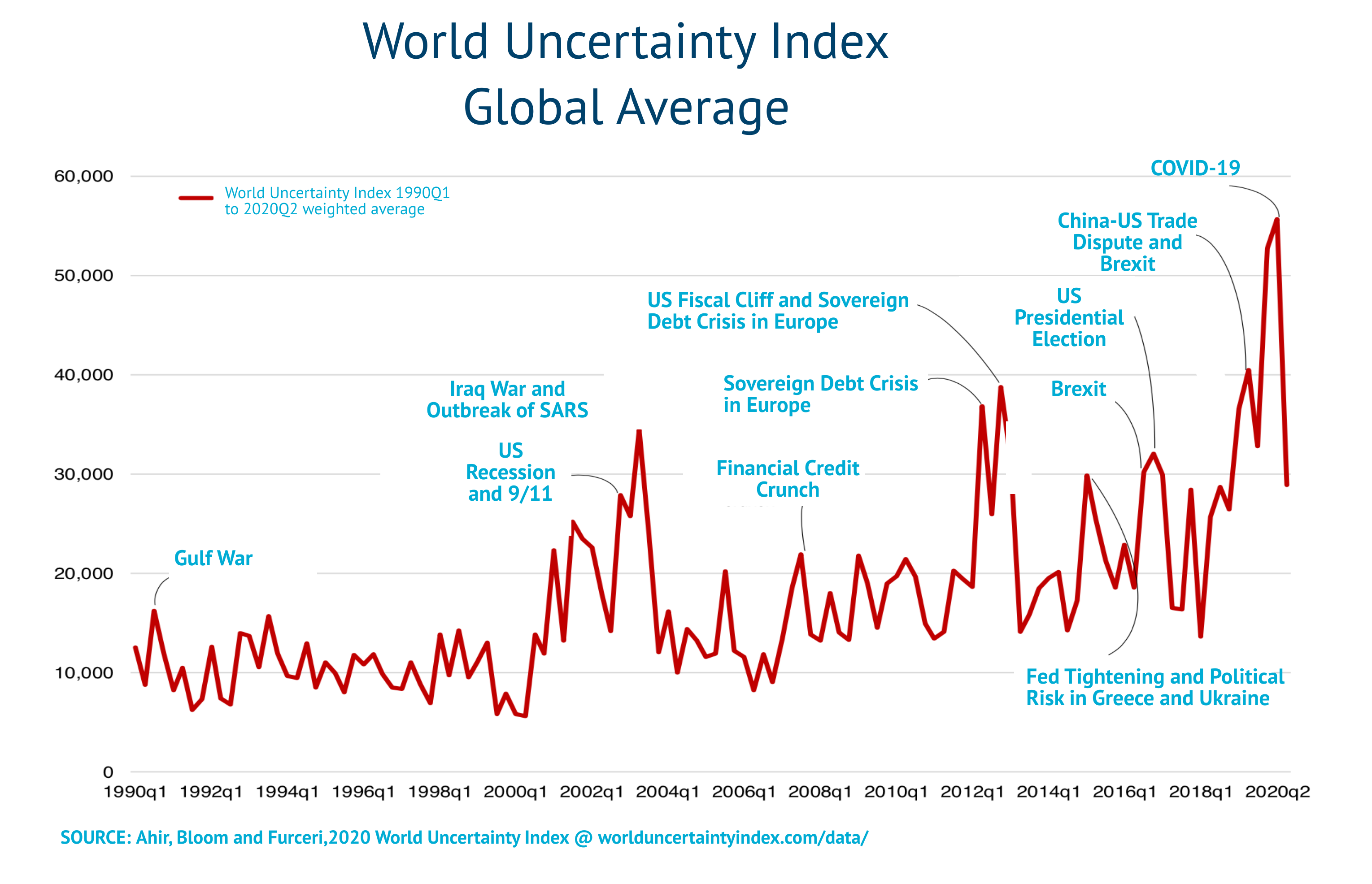

In a broadening of this approach to tracking events and impacts associated with economic uncertainty, Nick Bloom has worked with economists Hites Ahir and Davide Furceri of the IMF to develop the World Uncertainty Index (WUI). They used a series of regular country reports produced by the Economic Intelligence Unit as basis for quantifying references to economic uncertainty across 143 countries.

On a global basis over the last two decades, the WUI shows spikes around the 9/11 attacks, the SARS outbreak, the second Gulf War, the Lehman Brothers failure, the Euro debt crisis, El Niño, the Europe border-control crisis, the UK’s referendum vote in favor of Brexit, the 2016 US presidential election and recent US-China trade tensions. The WUI tends to rise closer to political elections – like the consequential one in two weeks. The authors point out that the index captures uncertainty created by specific near-term events but also long-term concerns such as tensions between North and South Korea.

The authors say global uncertainty has “increased significantly” since 2012. Notably, that uncertainty has not, however, translated into stock market volatility, perhaps because the political news has increasingly become difficult for investors to interpret.

Uncertainty tends to be synchronized among advanced economies, especially among the euro area countries. And, as countries move from regimes of autocracy towards democracy, uncertainty increases but declines as the degree of democracy increases and as the quality of institutions improves. The WUI offers an interesting window into what drives uncertainty in individual economies, as well. For example, China experiences higher levels of uncertainty in association with key leadership transitions. The UK experienced a spike in uncertainty at the time of the Scottish referendum.

When flat-lining is good

Trade as a component of the World Uncertainty Index has been low and nearly flat for most of the last twenty years, but has experienced a major spike in uncertainty over the last four years, in particular due to the US-China trade dispute and the setbacks in negotiating a smooth UK exit from the European Community. As Nicholas Bloom has put it, the United States, UK and China have been “exporting uncertainty”.

Trade versus COVID-19

For close to an entire year now, COVID-19 has been dominant and pervasive in our lives and the global economy. COVID-19 is novel by definition. The unknowns and uncertainty it wreaks show up everywhere – in stock markets, on Twitter and in the news. It should not be surprising, then, that the spike in uncertainty caused by COVID-19 far outstrips that caused by the US-China trade war.

But global trade tensions are not receding and the aftershocks of COVID-19 will continue to be felt in supply chain restructuring. That restructuring will take place in an environment of increasing restrictions on foreign investments, export controls, sanctions, and blacklisting of entities and individuals that multinational corporations can do business with. Long-established supply chain relationships may be less disrupted, but new relationships may not be initiated at the same rate or in the same way in times of high economic policy uncertainty.

While measuring the real impacts of economic uncertainty in still a relatively new concept, central banks and government agencies are beginning to pay attention, and to that end, it will be interesting to continue to take our collective pulse using indices like the EPU and WUI.

Hear Nicholas Bloom explain in his own words in this webinar presented by the Clayton Yeutter Institute of Trade and Finance at the University of Nebraska. Images are drawn from the slides used by Nicholas Bloom and accessible here.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).