Published 31 May 2019

An estimated 152 million children in the world today are in child labor. Provisions on labor issues have proliferated in trade agreements since NAFTA was implemented. But child labor is a complex problem requiring complex and situational solutions.

152 million children

Children are trafficked into slavery, an entire family is trapped in debt bondage to a father’s employer, and children are ordered to leave school during harvesting season. These travesties are too easily overlooked in political debates over the fine-tuning of a few words in a labor chapter of a trade agreement.

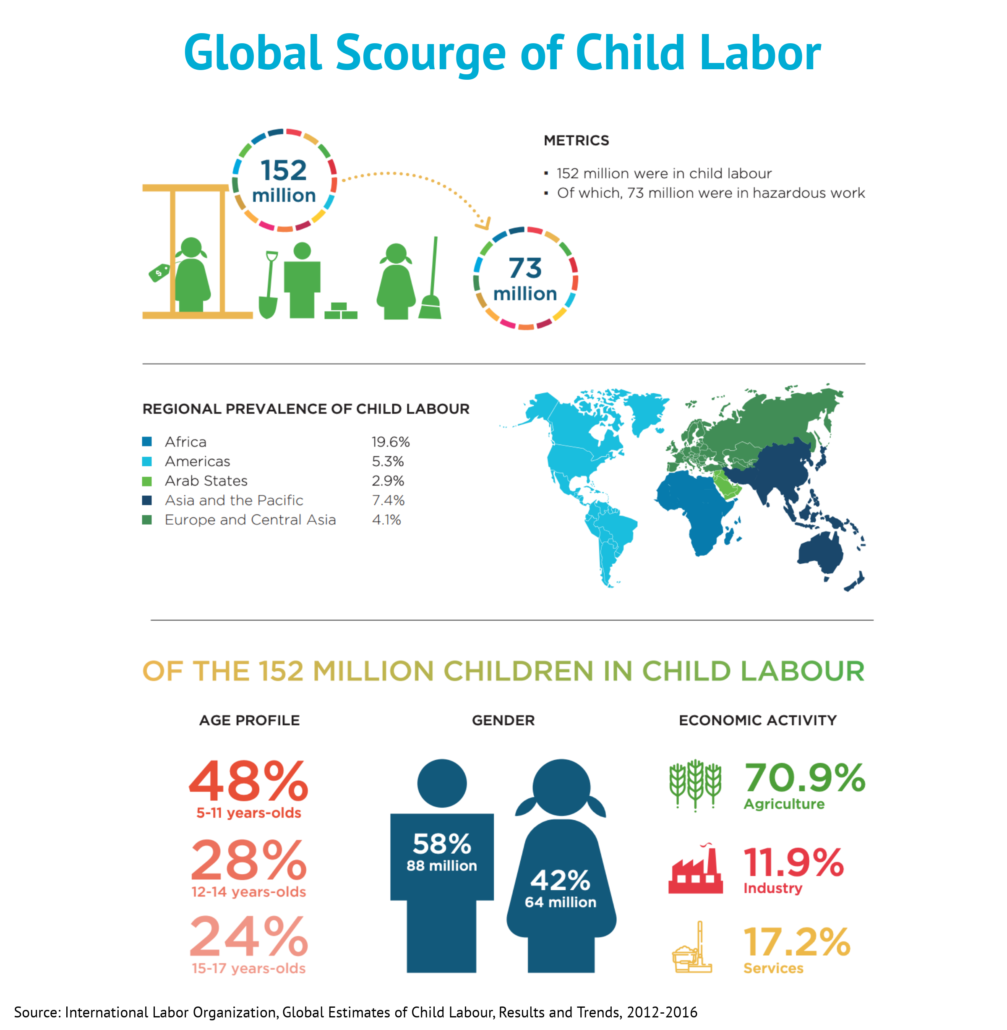

According to the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) 2017 estimates, at least 152 million children in the world today are in child labor. Nearly half are doing hazardous work. Just under half are below the age of twelve. As further context, another 25 million people are in forced labor – 64 percent of them are concentrated in the Asia-Pacific region. Over four million are victims of forced labor imposed by their own governments.

Progress has been made, removing an estimated 94 million children from dirty, backbreaking, and dangerous conditions between 2000-2016, but the scale of forced and child labor is still enormous and troubling for this day and age, in our hyperconnected world, when it should be ever more possible to track deep into supply chains.

Hidden in plain sight

Every year, the Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) issues a list of goods produced by child or forced labor matched to the country where the good is produced. The nearly 150 products on the list include some obviously suspect items such as poppies from Afghanistan, diamonds from the Central African Republic, and fireworks from China. Also cited are longstanding and well-documented abuses in the harvesting of sugarcane from Brazil, palm oil from Indonesia, and cocoa from the Ivory Coast.

The products are wide-ranging and could be found all around your household. They might include bananas from Ecuador, coffee from Vietnam, cotton from throughout Eastern Europe, shoes from Bangladesh, the gem on your finger from Tanzania, or even your kid’s soccer ball from India. We would all be lost without our cell phone and laptop chargers, but some of the cobalt ore in lithium-ion batteries is mined by children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. ILAB’s list tags 76 countries, breaking the goods into three large categories: half are agricultural commodities, about 28 percent are manufactured goods, and the remaining commodities are from mines or quarries, including minerals, metals, and coal.

ILAB cites six products with the most countries where child labor violations are occurring: gold, bricks, sugarcane, coffee, tobacco, and cotton. The report’s evidence often relies on surveys conducted by or with the support of national governments, an important step in the process of taking action to rectify the problem.

Complex problems require complex solutions

All that glitters: The flecks that make our cars glimmer and women’s eye makeup shimmer derives from mica, often painstakingly handpicked from dust. The non-profit organization Terre des Hommes estimates that up to 22,000 children work in mica mines in India alone, where about one quarter of the world’s mica is extracted. Over 40 companies are working with civil society organizations and government officials through the Responsible Mica Initiative to improve traceability in supply chains, promote better collection and processing practices among suppliers, and enlist authorities to put in place and enforce appropriate regulations for local operators.

Gold is traded today at around US$1,270 per ounce but adult laborers in Mali will be lucky to make US$4 a week lowering themselves into unstable, primitively dug pits. Children sit at the top, hauling up and carting off heavy loads of what they hope will be pay dirt, and are often exposed to liquid and vaporized toxic mercury used to refine the gold. Human Rights Watch estimates that 12 percent of the world’s traded gold is extracted under these conditions. Members of the World Gold Council appear to have worked on standards for “conflict-free” gold to reduce the incidence of gold mining benefiting armed groups, but there’s little evidence the industry is working toward sourcing in a manner that would reduce children’s involvement in mining.

Returning children to classrooms: For years, the Government of Uzbekistan routinely coerced around one million of its citizens to meet cotton picking quotas at harvesting time or risk losing their social benefits. Schoolteachers were told to close their classrooms and mobilize students to the fields. The yields were destined for China, Bangladesh, Turkey and Iran for textile production.

A combination of international pressure and support over the course of a decade has induced the Government of Uzbekistan to both take steps to meaningfully reduce the incidence of child labor, and to allow private investments to modernize cotton production. It has been a long road with many interventions along the way. Hundreds of companies including Tommy Hilfiger, Gap, West Elm, and Target signed an Uzbek Cotton Pledge not to knowingly source Uzbek cotton for their products.

A modest role for trade agreements

The ILO was founded 100 years ago in 1919, but Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor was only adopted by member governments in 1999. The NAFTA was a trailblazing agreement, introducing in 1994 the first labor provisions between a developed and developing country in a free trade agreement.

Twenty-five years later, the US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement’s (USMCA) labor chapter is more fully elaborated, touching on a wide variety of labor issues but also expanding upon previous language regarding basic and universally recognized labor rights, including child labor. The parties, Canada, Mexico and the United States, affirm they will adopt and maintain in their respective statutes and regulations, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor and the effective abolition of child labor, prohibiting the worst forms of child labor.

Article 23.6 of the USMCA chapter on labor goes even further, committing each of the three governments to “prohibit the importation of goods into its territory from other sources produced in whole or in part by forced or compulsory labor, including forced or compulsory child labor.”

The United States had already taken important steps to close a loophole in US trade law prohibiting the importation of goods into the United States produced by forced, convict, forced child, or indentured labor. The U.S. Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 removed an exemption that previously allowed such importation if the goods were not produced domestically in sufficient quantities to meet U.S. consumer demand. ILAB’s 2018 report notes an increase in enforcement actions by U.S. Customs and Border Protection of this provision, citing examples such as the detaining of certain toy shipments from China and the issuance of an order to detain all cotton from Turkmenistan or products made in whole or in part from Turkmen cotton.

Beyond words: Collective action

There is no single solution to the various forms of enslavement that still plague millions of children around the world. Progress depends heavily on government actions to implement, monitor, and enforce legal frameworks to protect children and offer social supports to victims; on producers and their ability to induce industry-wide change through the supply chain; and, on civil society organizations to provide technical support and “backbone” services to coalitions seeking to work together. All play critical roles and none can be as effective without the insights, resources, and leverage of the other.

Provisions on labor issues have taken hold and proliferated in trade agreements since NAFTA was implemented. Debates have ensued over the binding nature of those provisions and how to enforce them. Is cooperation and capacity building more effective than the threat of dispute settlement under a trade agreement, or do you need both?

The answers depend on what outcome you seek. A cynic, or a realist, might say these debates settle politics more than produce tangible benefits in the most egregious cases such as the ones described herein. Targeted sanctions have worked in specific cases, especially under threat of the withdrawal of unilateral trade preferences. But for widespread and demonstrable improvements to lives of the millions of children who are mainly not included in the scope of trade agreements, only concerted action in their communities and throughout global supply chains will make the difference.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).