Published 07 December 2018

What's important about these summits is not the prepared statements delivered at the main table, but the frank discussions and informal meetings that take place in the corridors and meeting rooms around the main conference.

Leaders of the G20 just met in Argentina – who and…why?

The leaders summit celebrates its 10th anniversary this year. You can think of the G20 leaders summit as the principal shareholders in the global economy (the leaders of 20 nations) meeting with their “executive board” (heads of the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund, World Bank and other major international organizations responsible for keeping the global economic, finance and trade operating systems in working order). It also includes civil society engagement through platforms called the Business 20, Civil 20, Labour 20, Science 20, Think 20, Women 20 and Youth 20.

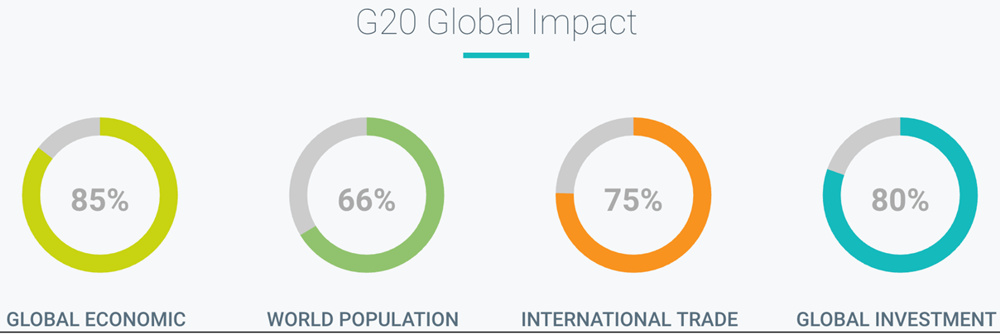

More specifically, the “shareholders” include the G7 nations — Canada, the United States, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the European Union — as well as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and South Africa. The G20 encompasses 2/3 of the world’s population and their economies account for approximately 85 percent of global economic output and 75 percent of international trade.

The G20 was originally a meeting of finance ministers, their deputies and central bankers, that formed in 1999 in the wake of the Asian and Russian financial crisis. It was raised to the leaders’ level in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis when then-US president George W. Bush convened a summit in Washington in November 2008 to address the crisis.

What does the G20 discuss?

The G20 has a de facto standing agenda which includes:

- Multilateral trading system. In Argentina, the leaders affirmed its importance but there is no sense the WTO’s Doha round is going anywhere. The United States is also unhappy with the operation of the WTO itself, especially its dispute settlement mechanism. Canada, working with like-minded countries, has taken the lead in trying to find a solution to make the process more transparent and efficient.

- Promoting international investment. Barriers to investment continue to plague G20 economies. The G20 discussed the need of governments to further open their economies.

- Achieving sustainable fiscal policy. This means saving in good times so you can spend in recession and then get back to balance as quickly as possible.

- Supporting sustainable development. With the conclusion of the Millennium Development plan in 2016, nations are now committed to 17 goals in the new UN Sustainable Development Agenda to be achieved by 2030, including zero poverty, gender equality, good health and wellbeing, clean water and sanitation, reduced inequalities, decent work and economic growth.

- Resistance to protectionism. Global Trade Alert reports that since 2008, notwithstanding the G20 pledge for standstill at the London 2010 summit, governments have taken 11,743 protectionist measures ranging from local content requirements to discriminatory regulatory practices. According to the WTO, G20 trade restrictive measures for 2018 are more than six times larger than those recorded in 2017 and the largest since this measure was first calculated in 2012. WTO Director General Roberto Azevêdo has called for immediate action to de-escalate the situation.

The host country agenda

Every summit has its own theme and specific priorities the host country helps to shape. This year the summit was hosted by Argentine President Macri under the theme, “Building Consensus for Fair and Sustainable Development”.

Macri’s priority topics included:

- The future of work: Unleashing people’s potential. G20 leaders want to avoid a scenario in which one nation seizes paramountcy in artificial or cyber-intelligence, leaving the rest far behind. The emergence of new technologies has led to the development of new forms of work that are rapidly changing production processes worldwide. Policy responses need to ensure that embracing technological change will not engender exclusion, social disintegration or backlash. Education is at the crux of this debate.

- Infrastructure for development: Mobilizing private resources to reduce the infrastructure deficit. The global infrastructure gap projected from now to the year 2035 amounts to US$5.5 trillion according to some estimates. Mobilizing private investment toward infrastructure is crucial to closing the global infrastructure gap. It can also ensure a better return for those who today save and invest. This is a win-win objective and it requires international co-operation. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a major source of infrastructure funding but BRI financing on partner nations’ debt levels, governance and susceptibility to Chinese influence are increasingly under scrutiny.

- A sustainable food future: Improving soils and increasing productivity. The G20 countries are key players in the global food system. Their territories account for about 60 percent of all agricultural land and for almost 80 percent of world trade in food and agricultural commodities. Approximately 10 million hectares of cropland are lost every year due to soil erosion. Food production must double during the next 30 years to meet projected population growth and dietary changes.

What’s the outcome of G20 meetings?

Sometimes it’s a victory merely to produce a consensus “communiqué” detailing areas of agreement. Most of the “action” happens in bilateral meetings between leaders on the sidelines of plenary sessions. The big news from this year’s summit came out of the working dinner between Presidents Trump and Xi that produced agreement to work on a trade deal over the next 90 days. Find the Leaders’ declaration issued in Argentina here.

Do we really need a G20?

At a time when globalization, the maintenance of a liberal international order and multilateral co-operation are under question, the G20 is an important forum to discuss, and hopefully advance, common global interests. More people will work on the draft of the final communiqué than may read it but the process of getting there is what really matters. The ongoing meetings between central bankers and finance ministers (the original G20) now include other ministerial meetings as well as regular discussions with business, civil society and think tanks.

The G20 filled a gap in the architecture of top table meeting places at the UN and G7. The permanent members of the United Nations Security Council – Russia, China, France, Britain and the U.S. – represent the world of 1945 and the early Cold War. As we witness with Syria and other crises, getting the Security Council to act constructively is very difficult. Reforming it is an exercise in futility.

The G7 group of leaders – the United States, France, Britain, Germany, Japan, Italy and Canada – was created in 1975-1976 following the economic crisis that OPEC induced. It is Eurocentric. It doesn’t include China, India or Brazil. Russia joined in 1998 but it was suspended in 2014 after its invasion of Crimea. The G20 complements at the leadership level the work of the other major financial and economic institutions: the “Bretton Woods twins” – the IMF and World Bank – and the WTO.

As Council on Foreign Relations Fellow Stewart Patrick observes: “The G20 has the potential to act more nimbly and (at least in principle) transcend stultifying bloc politics that afflict the United Nations and other universal membership organizations.” Some suggest that the G20 should create a parallel foreign ministers’ track, arguing that the political and the economic go hand-in-hand, but this is probably a bridge too far for now.

So, the G20 makes sense. Like the G7, much of the G20’s value is in its process. What is important about these summits is not the prepared statements delivered at the main table, but the frank discussions and informal meetings that take place in the corridors and meeting rooms around the main conference. Winston Churchill, who popularized the word “summitry” observed that “jaw-jaw” between leaders is better than “war-war”.

Further reading

The official Argentine site has useful information, as does Global Affairs Canada. The best Canadian source for G20 documentation, with a chronology of past summits, is the University of Toronto’s G20 Information Centre managed by John Kirton. The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) in Waterloo does excellent research work on G20 issues. Both are also involved in the G20 Insights project that has produced a series of excellent policy briefs drawing on work by the Think 20.

This article is a shortened version of the original primer entitled, A Canadian Primer to the G20 Summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina, November 30-December 1, 2018. That primer and others produced by Colin Robertson can be found here.

Feature photo credit: G20

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).