Published 12 January 2017

Trump has proclaimed that he would “rip up” existing trade agreements, renegotiate the NAFTA, and impose a 35 percent tariff on imports from Mexico and a 45 percent tariff on China imports.

President-elect Donald Trump has variously proclaimed that he would “rip up” existing trade agreements, renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and impose a 35 percent tariff on imports from Mexico and a 45 percent tariff on imports from China.

Question: Since the legislation to implement NAFTA and other free trade agreements (FTAs), as well as U.S. obligations under the WTO, was enacted by Congress, can President Trump unilaterally carry out his threats?

Answer: The short answer is “yes,” at least in the short term. The president has constitutional power over foreign affairs, and multiple statutes enacted by Congress over the past century authorize the president to impose tariffs or quotas on imports and regulate foreign commerce in other ways.

Question: Which statutes can be used to withdraw from our trade agreements, and what effect would that have on the tariffs applied to goods imported from Mexico if we withdraw from NAFTA?

Answer: The NAFTA (like other FTAs) enables any member to withdraw after giving six months’ written notice to the other parties. Exercising authority over foreign affairs, a president could service notice of cancellation of the agreement to Canada and Mexico (and other FTA partners). By itself, U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA would not raise U.S. tariffs on imports from Canada or Mexico.

Since the first Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, U.S. tariffs have been lowered by presidential proclamation within the statutory limits authorized by Congress. By issuing a new proclamation, or by revoking the earlier proclamation issued by President Clinton lowering tariffs under NAFTA, Trump could revert to the Most Favored Nation rates applied to countries with which we do not have trade agreements (averaging around 3.5 percent ad valorem, but with much higher rates on items like clothing and footwear).

Question: If the average tariff rate reverts to around 3.5 percent ad valorem, how could the president apply a 35 percent tax on imports from Mexico?

Question: If the average tariff rate reverts to around 3.5 percent ad valorem, how could the president apply a 35 percent tax on imports from Mexico?

Answer: To implement the 35 percent rate threatened by Trump against imports from Mexico, he could invoke Section 201 of the NAFTA Act, which enables the president to proclaim “additional duties” – following consultation with Congress – as necessary and appropriate to maintain the “general level of reciprocal concessions” with Canada and Mexico.

This is not a defined standard, leaving room for Trump to construct an argument that the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico justifies the increase, or that Mexico imposes its value added tax on imports from the United States, but not the other way around, since there is no U.S. value added tax.

Question: Wouldn’t our obligations in the WTO to maintain upper limits on our tariffs preclude the president’s ability to raise tariffs on Mexico to such a high level?

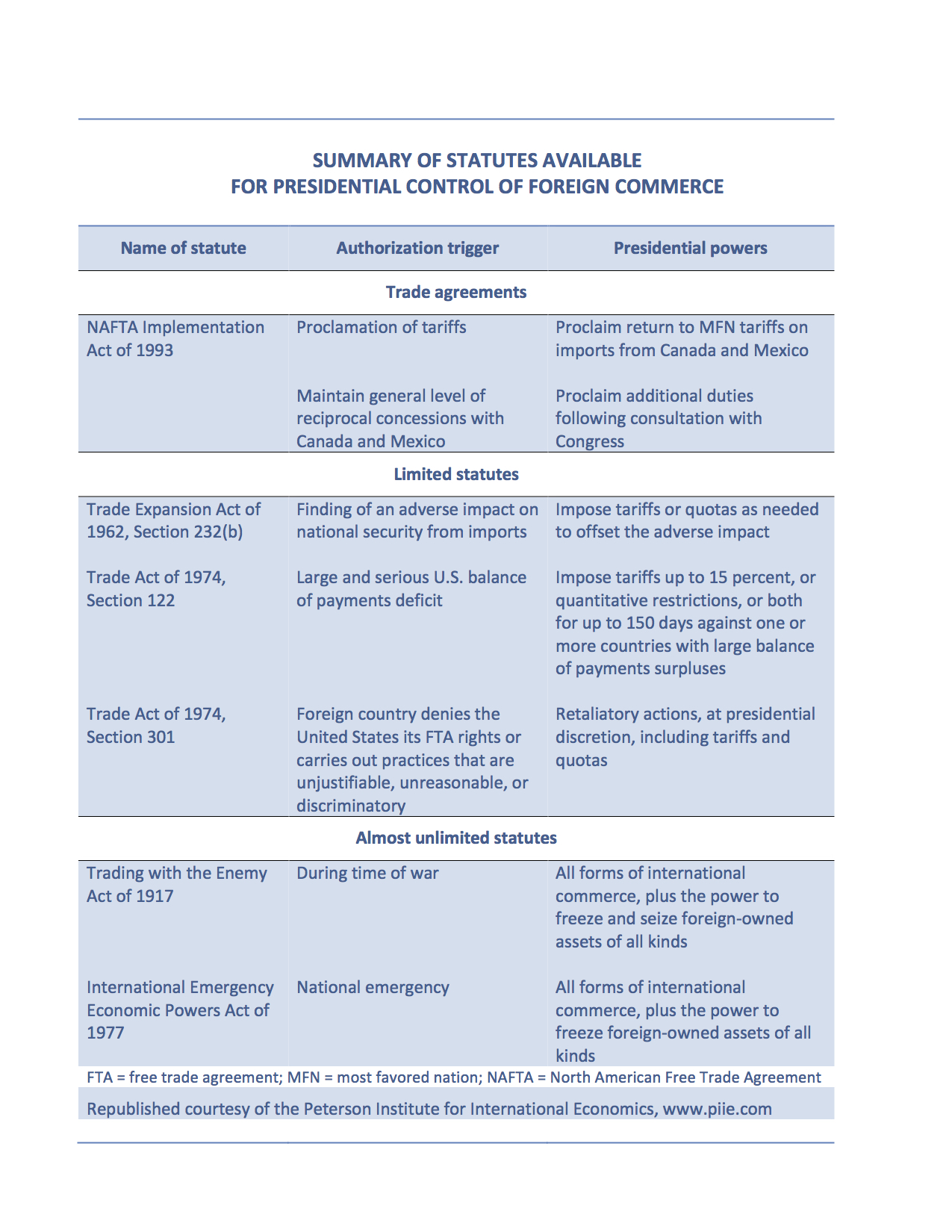

Answer: To raise tariffs against Mexico to 35 percent, thereby breaching the United States’ WTO commitments, Trump would very likely need to invoke other limited statutes. There are three laws he could point to, included in the table above.

Section 232(b) of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 relates to protecting or strengthening national security. Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 grants the president special powers to impose a tariff of up to 15 percent or quantitative restrictions, or a combination of the two, for up to 150 days to remedy a balance-of-payments deficit.

Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act allows the president to retaliate for unfair trade practices abroad. Using Section 301, President Trump could impose tariffs in retaliation for a manipulated or undervalued exchange rate, market access barriers, or anything else that burdened U.S. exports.

Question: Would our trading partners have the right to retaliate – for example, by raising tariffs on products from the United States?

Answer: Using any of these statutes, by breaching its bound tariffs, the United States would give its trading partners grounds to complain under international law and the right to retaliate.

Question: If U.S. obligations in the WTO create an upper bound on tariffs we can apply to any WTO member regardless of whether we have an FTA with them, what happens if we withdraw from the WTO?

If Trump actually “pulled out” of the WTO, the Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff bindings – that is, the rate we are limited to under our WTO obligations – might cease to have legal effect. In that event, U.S. tariffs could conceivably revert to the onerous Depression-era Smoot-Hawley levels. This scenario seems far more cataclysmic than envisaged by Trump’s campaign rhetoric.

Question: What about Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the power “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations”?

Answer: For his contemplated actions, President Trump can cite the specific delegation of congressional authority, in NAFTA and other FTAS, to proclaim tariffs, and the foreign affairs powers of the president to terminate NAFTA or other FTAs.

Question: Wouldn’t the Trump Administration face insurmountable opposition to measures with potentially far-reaching economic costs and which appear to take Congress out of the equation?

Answer: As self-inflicted damage to the U.S. economy (see Chapters 2 and 3 of the Peterson Institute brief) became evident and widespread, Trump would face vigorous court challenges by adversely affected U.S. firms and possibly some states, arguing that the president had exercised powers and invoked statutes in ways that the Constitution or Congress never intended. In addition, Congress would debate new bills to revoke powers delegated to the president under previous statutes.

Any effort to block Trump’s actions through the courts, or amend the authorizing statutes in Congress would be difficult and would certainly take time.

No matter the outcome of domestic legal battles, if Mr. Trump actually withdraws from U.S. trade agreements, or if he imposes high tariffs, even as a threat or tactical maneuver, foreign countries will soon retaliate. Enormous economic damage to U.S. firms, workers, and communities could ensue from a trade war long before the legal battlefield is cleared.

To create this Essential, TradeVistas asked Mr. Hufbauer permission to answer our questions based on Chapter 1 of “Assessing Trade Agendas in the US Presidential Campaign,” published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in September 2016. We highly recommend reading the extended brief, which provides additional context, and models the impact to the U.S. economy and workers under three “what if” scenarios for Trump’s trade policies.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).