How to use it

Optimizing export controls for critical and emerging technologies

Published 16 April 2024

In response to changing geopolitics, the US has begun to reassess threats to national security, competitiveness, and technological leadership. Lawmakers and policymakers are reviewing export controls for effectiveness, with some considering expansions. This Center for Strategic and International Studies report, the second of a three-part series, evaluates export control lists, rule expansions, and other weapons of economic statecraft.

Here’s how to use the report entitled Optimizing export controls for critical and emerging technologies: Reviewing control lists, expanded rules, and covered items.

Why is the report important?

The report comes at a time when rules are under reconsideration and therefore can make a timely contribution to the debate underway. To date, policymakers and lawmakers have tended to expand rules without taking into consideration the capacity needed to apply and enforce the rules. This report importantly advises policymakers and lawmakers on how rules should tightened or loosened in order to both ease the administrative burden on enforcement authorities and also reflect the realities of the market.

What’s in the report?

The report includes eight principal sections:

Introduction; Bureau of industry and security; Entity list; Country listings; Foreign direct product rules; Catch-all controls

- As national security threats evolve and economic prosperity and geostrategy now go hand in hand, policies to control critical and emerging technologies have become a cornerstone of US national security strategy, spurring a rethinking of controls on traditional dual-use items on the Commerce Control List (CCL), including reviews and potentially decontrol of some items; security under export controls is defined at the margins of technological advancement rather than by legacy items already within reach of potential adversaries’ technical capacity. (pp. 1-2)

- The US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security’s (BIS) administration and enforcement capabilities are central to the CCL’s scope; BIS faces challenges in obtaining funding and staffing it needs to serve US national security and foreign policy interests. (p. 4)

- BIS enforces lists and rules meant to prevent items, software, and technology from supporting end uses and end users posing a risk to US national security and foreign policy; increasingly, the aim is to curb not only homegrown technology but also technology manufactured in allied and partner nations that incorporates or relies on US-controlled technologies; BIS lists and rules could be improved and updated through a review process. (pp. 5-6)

- The Entity List subjects US persons to license requirements for the export, reexport, and in-country transfer of goods, software, and technology to select foreign entities; applications for exports to entities on the list are subject to specific license reviews at different levels of restrictiveness; an interagency End-User Review Committee (ERC) reviews proposed changes to the list; the ERC annually assesses the list for updates; the Entity List is distinct from other US government lists and regulated under a different authority. (pp. 7-8)

- In 2008 the Entity List’s mission was expanded to combat broader threats to US national security and grew again in 2014 to target entities concentrated in China and Russia, reflecting the evolving threat landscape for the US; the Entity Lists’s rules point toward a US foreign policy that chokes off adversaries’ access to technology critical to national security; these shifts have resulted in an expanded List; despite expansion of the list, only about 7 entities have been removed annually since 2008; BIS can do more to remove entities that no longer post a threat to ensure the List is as tight as possible. (pp. 8-9)

- The US government maintains formal and informal lists imposing trade controls and sanctions against designated foreign countries, including: 1) a State Department list barring the sale of certain military technology and technical data to specific countries, 2) the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control economic and trade sanctions list, and 3) the Commerce Department’s Commerce Country Chart (CCC) (a supplement to the EAR) list of countries subject to comprehensive controls; the CCC helps with decisions over whether to submit license applications to BIS for approval to export certain items. (pp. 10-11)

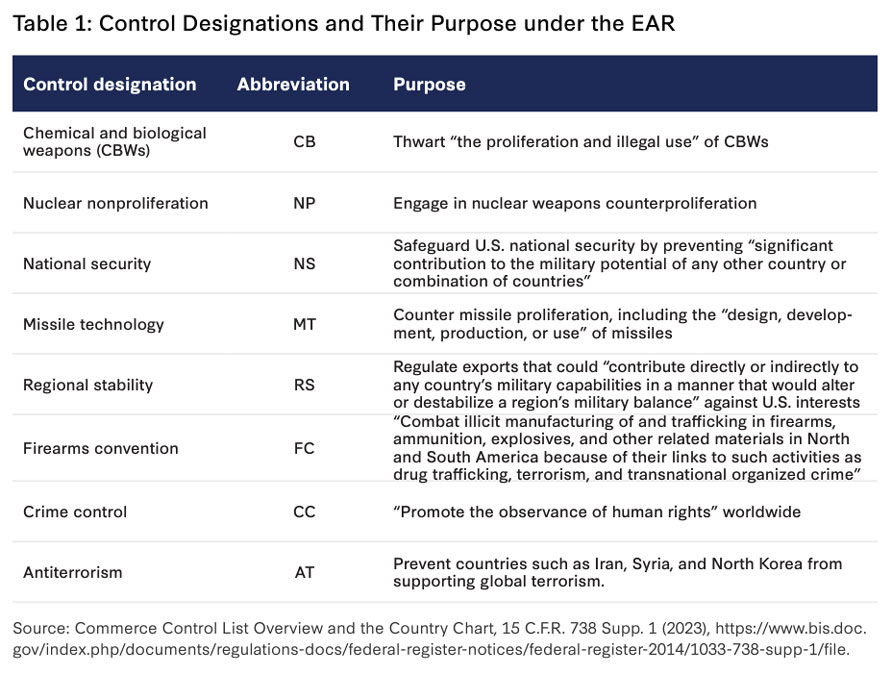

- The EAR contemplates multilateral and unilateral reasons for control to inform BIS license application reviews; the Commerce Department also complements the CCC by sorting countries into five groups reflecting each country’s domestic export control policies and membership in multilateral regimes; amendments in 2022 and 2023 adjusted controls targeting China and Russia, reflecting the changing security environment; BIS should contemplate additional changes. (pp. 11-13, Table 1)

- US export control laws apply extraterritorially; nine foreign direct product (FDP) rules apply to foreign-made items that are the direct product of certain types of US-origin equipment, software, or technology and destined for designated countries; FDP rules have been expanded in recent years to target threats to US national security from China and Russia; expanded use of FDP rules stretches enforcement capabilities, making BIS less effective; before expanding FDP rules, lawmakers should consider BIS’s ability to enforce them; using FDP rules risks bullying foreign allies and partners into compliance by threatening their private sectors and driving those private sectors to design US tech out of their supply chains. (pp. 14-17, Table 2)

- Catch all controls subject the export, reexport, and in-country transfer of items not on any export control list to license requirements if destined for specific end users or end uses, regulating sale of items that could facilitate chemical and biological weapon, missile proliferation, and nuclear end uses of concern; catch-all controls block access to items not subject to export controls but that the government knows or suspects can enable end uses that raise concerns; multilateral regimes also incorporate catch-all controls which can be seen as enabling a balance between security-driven control requirements and economically-driven trade-facilitation imperatives; the US government should continue to collaborate with allies and foreign partners to enhance efficacy of export controls. (pp. 18-20)

- The Denied Persons List includes people who have violated US export control laws and regulations and is not specific to any country or item; the Unverified List includes companies or individuals who fail to provide sufficient documentation or information to verify the legitimacy of their intended transactions and is intended to address unauthorized end uses or diversion of controlled items to unauthorized locations; persons can be removed from the Unverified List by demonstrating that they are acting in good faith or through proof of legitimate end uses; the Military End-User List lists companies deemed to be military end users and prohibits listed parties from receiving certain items without a license from BIS. (pp. 20-21)

Reexamining the commerce control list; Commerce control list items

- The CCL is transforming as advanced technologies are added to BIS controls; items on the CCL should be reviewed and revised more frequently given rapidly changing technologies, evolving threats, and diversifying capabilities; reviews should consider the capabilities of countries of concern to make items without US input and the role of economic partners and allies in supporting control policies; the review should divide items according to whether export controls should be loosened or sustained/tightened. (p. 22)

- A review of the controls in place should consider the impact on the US, allies, and actors of concern, including effects on US technological capabilities and R&D, US industry competitiveness, and US security interests; alignment with allied and multilateral export control regimes and whether it would enhance or undercut allied industries and security interests or affect cooperation with the US; and whether an action would prevent countries of concern from sourcing the restricted item from abroad or indigenously. (pp. 23-24)

- Many items on the CCL are also controlled under multilateral export control regimes, including four of which the US is a member: the Wassenaar Arrangement (conventional arms and dual-use goods), the Nuclear Suppliers Group (nuclear material and related technologies), the Australia Group (chemical and biological weapons and related goods), and the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) (missiles and related technologies); all coordinate export controls and stop proliferation of sensitive technologies to actors and end users of concern without identifying target countries; the US is also a party to UN Security Council arms embargoes on particular countries or regions; multilateral controls reduce the number of suppliers of arms to actors of concern making controls more effective overall. (pp. 24-25)

- CCL items are either subject to multilateral controls (in addition to US controls) or controlled unilaterally; BIS can more easily add or remove unilaterally controlled items from the CCL; for multilaterally controlled items the US must seek consensus to add or remove them from controls which is more complicated and could require Congressional approval; if the US wishes to remove an item from control without consensus multilaterally it could choose to loosen controls with the risk of undermining the control regime. (pp. 25-26)

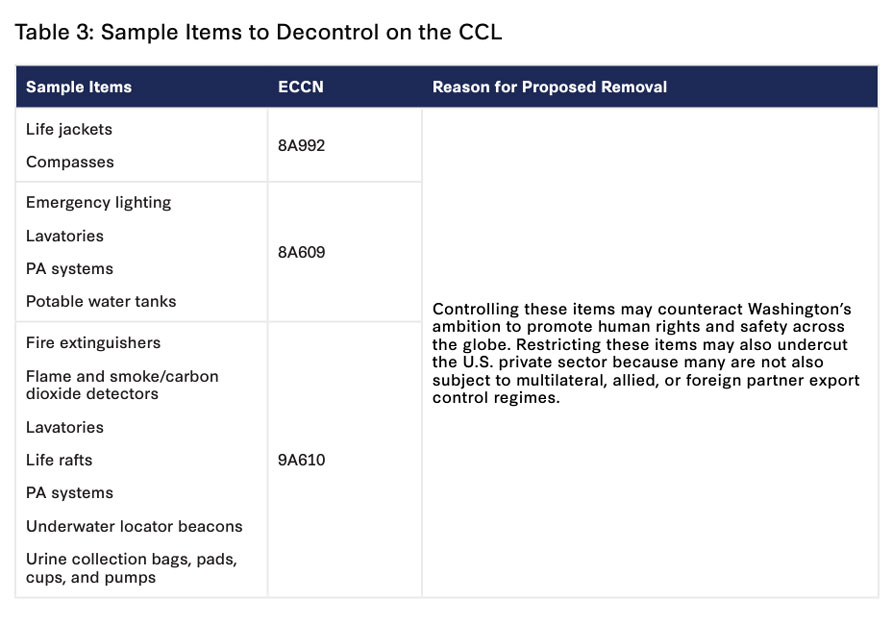

- Items currently on the CCL primarily related to health and safety (i.e. fire extinguishers and life jackets) can be decontrolled now to free up BIS licensing and enforcement capabilities; items not controlled by US allies, that countries of concern can also easily design and manufacture, and that are not essential to functioning of a military item can be removed from the CCL without damage to US national security or harm to US manufacturers. (pp. 27-28, Table 3)

- In reviewing items for potential decontrol, BIS should consider whether the presence of the US, its allies, and partners is large enough in a specific good’s market to make controls effective, taking into account foreign availability as well as a critical analysis of where the US falls in the market landscape, i.e. leading or falling behind. (pp. 28-30)

- Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can play a significant role in both commercial and defense applications and are controlled under the MTCR and by the UK, Canada, EU and the US for the potential to deliver nuclear and other controlled technologies; the US and Israel are the largest producers and sellers of UAVs with China emerging as a major producer and exporter and the world leader in combat UAVs; CCL controls should be tailored to the technology margins where the US maintains a leading edge but loosened where China dominates the market to allow US firms to compete. (pp. 30-31)

- Field program gate arrays (FPGAs) are integrated circuits that can be configured for special functions in the field without hardware replacements or modifications so have wide applications, including in military systems and critical infrastructure; FPGAs are controlled by the Wassenaar Arrangement and Canada, the UK, EU, and the US to limit proliferation of sensitive technologies; FGPAs are made with components and expertise from multiple countries so maintaining export controls can disrupt US technological progress; the US has a technological lead in the advanced market while China is performing well in the low-end market and making advancements in high-end capacity; US export controls should adapt to China’s dominance in legacy products while curbing China’s ability to obtain advanced design and manufacturing capabilities. (pp. 31-32)

- Radiation-hardened electronic components are components, CPUs, and sensors that are less susceptible to damage from exposure to radiation and extreme temperatures and are used in the aerospace, defense, nuclear, and medical industries; they are subject to US export controls and the Wassenaar Arrangement; North American companies dominate the market, with the Asia-Pacific market growing at the highest rate, bolstered by research in China, India, and Japan, with China investing heavily in producing and indigenizing these products; current US primacy in this sector makes controls workable in coordination with allied governments. (pp. 32-33)

- Machine tools cut, shear, and cast metal and other materials to create products and parts and are increasingly sophisticated, creating intricate technologies and electronics with use in both commercial and defense sectors; exports are controlled by the CCL, the Wassenaar Arrangement and the Nuclear Suppliers Group; Asia is the largest market for machine tools; Japan, Germany, and the US are the largest producers of machine tools but many of their companies have production in China; China is currently incapable of producing certain high-end machine tools despite growth of R&D there; controls on high-end machine tools are workable because of US and allied dominance so long as the US takes a multilateral approach to controls working closely with Japan and Germany, who dominate global supply. (pp. 33-34)

- Lasers are used in medical, commercial, telecom, scientific, and defense industries with a wide range of applications; lasers are subject to US export controls and controlled under the Wassenaar Arrangement and the Nuclear Suppliers Group; Asia is the largest market with China the largest component of the market; China has laser technology comparable to the US and allied countries, with the US and its allies maintaining some control and a technological advantage over lasers in high-end applications like EUV lithography and lidar; given China’s growing hold of the lidar sector and the US imperative to remain competitive and a global leader in lidar, BIS should loosen controls to provide commercial opportunities to US firms in the sector. (pp. 34-35)

- Advanced materials are materials or substances with unique properties or applications in advanced technologies; polyimides are synthetic polymers that possess superior strength, thermal stability, and resistance to radiation, so are used in aerospace and military applications (i.e. Kevlar); the UK, EU, Canada, the US and the Wassenaar Arrangement all control various polyimides; Asia is the largest market for polyimides while US and allied firms are the dominant suppliers; US controls are still effective but BIS should review controls frequently based on thickness, with thicker polyimides more important for control; looser controls on thinner products would allow US firms more competitive opportunities. (pp. 35-36)

- Aviation testing equipment are tools used to maintain aircraft hydraulic and electronic systems; equipment is subject to export controls to ensure it is not diverted to entities of concern for military purposes; Asia is the largest market and fastest-growing region; China is working to develop its indigenous capacity but has not caught up to industry leaders like the US, giving US export control authorities more leeway in influencing China’s rise in this sector; tight US controls are warranted to restrict Chinese access to technologies that enable China to build a domestic aviation industry and capabilities. (pp. 36-37)

How to apply the insights

-

This section explains the nexus between US export controls and multilateral regimes, including the difficulty of removing certain products from export controls in light of US multilateral obligations.

- The paper then highlights products that can and should be removed from control to free BIS capacity and resources, while evaluating specific sectors where BIS should either loosen or maintain controls.

- This section is helpful for policymakers seeking to better understand items subject to controls and the challenges or opportunities they face in advancing business opportunities and technological developments while working under export controls.

Policy recommendations

- Revise BIS Lists to better tackle today’s security challenges: The annual review process for the Entity List should restart in order to allow for removals and tighten the list, rather than allow it to be expanded indefinitely; use of FDP rules has similarly expanded, potentially beyond BIS enforcement capabilities; US policymakers should carefully consider the government’s ability to enforce rules before expanding them further; the government should also review countries of growing geopolitical importance given their proximity and relationship to countries of concern, and upgrade or downgrade their status accordingly. (pp. 38-39)

- Undertake a comprehensive review of CCL items: decontrol items that impose undue enforcement burdens, needless compliance work, pose no undue threat to national security, and/or involve safety features rather than offensive capabilities; review items on the CCL list balancing national security, economic impacts, and foreign partner interests in deciding whether to augment, reduce, or maintain export control designations. (pp. 39-40, Table 4)

How to apply the insights

- This section gives practical and achievable recommendations for US policymakers and lawmakers to consider as they review BIS capabilities and the relevance and effectiveness of current US export controls to meet current geopolitical challenges presented by China and Russia.

Conclusion

The Optimizing export controls for critical and emerging technologies: Reviewing control lists, expanded rules, and covered items report evaluates the rules and lists underpinning US export controls and the agency that administers them, providing timely analysis and recommendations for policymakers to consider as the lists are revised to make them more effective in a time of changing geopolitical risks.

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- The false logic of sanctions as deterrents

- AI arms race shakes tech, trade, and truth

- Techno-nationalism and its impact on geopolitics and trade

External Resources

-

Optimizing Export Controls for Critical and Emerging Technologies – Center for Strategic and International Studies

Part one of a three-part series. -

Riskful Thinking: Navigating the Politics of Economic Security – European Union Chamber of Commerce in China and China Macro Group

A review of the steps EU, China, and the US are taking to "de-risk" each economy. -

Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains: An Affirmative Agenda for International Cooperation – Center for Strategic and International Studies

An explanation of the complexities of geopolitics snarling these supply chains.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).