Trade and geopolitics

Supply traceability: How US trade policies affect Vietnam's garment industry

Published 11 April 2023

Vietnam’s garment and textile industry has been a vital driver of the country’s economy. While economic integration with the global economy and trade liberalization have created lucrative opportunities for the industry, they have also raised challenges for businesses such as ensuring compliance with fundamental labor rights, including eliminating forced labor. The article examines the impact of the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act on the garment and textile industry in Vietnam.

During the last few decades, Vietnam's garment and textile industry has grown into a vital driver of the country's economy, boosting the country to the second-largest garment and textile supplier in the world. Economic integration and trade liberalization have created numerous opportunities for the industry while also raising challenges for businesses. Among those issues is ensuring compliance with fundamental labor rights, including eliminating forced labor, established by different importers. To be more specific, the use of forced or compulsory labor is prohibited under Convention No. 29 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), which Vietnam ratified in 2007.1 The elimination of forced labor is a fundamental labor right established in the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA)2 and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) Agreement3 as well as the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) Confederation of Employers (ACE) Statement.4

Recently, the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (the “UFLPA” or “Act”) signed by President Biden on December 23, 2021, was enacted to address the plight of Uyghurs and other persecuted minority groups in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (the “XUAR”). The Act is likely to have a considerable impact on several industries, notably the textiles industry and specifically those believed to be using Xinjiang-sourced materials in their production. Countries and companies which continue to allow Xinjiang-sourced materials into their supply chains will no longer be able to access the lucrative US market.

Vietnam is currently the second largest import partner of the US and thus, this Act has tremendously impacted Vietnam’s garment and textile industry as the industry is heavily dependent on raw materials from China. The forced labor issues are now becoming a matter of urgency for Vietnamese garment and textile companies. They must tackle forced labor issues not only at the domestic level but also at the international level for the whole supply chain. Thus, this report enhances our understanding of how forced labor prevention policies are impacting Vietnam’s garment and textile supply chain. The study also examines how Vietnamese garment and textile businesses connect domestic and international supply chains for tracking and tracing products’ origins to ensure that forced labor practices have no place in the industry.

Vietnam’s garment and textile industry – at a glance

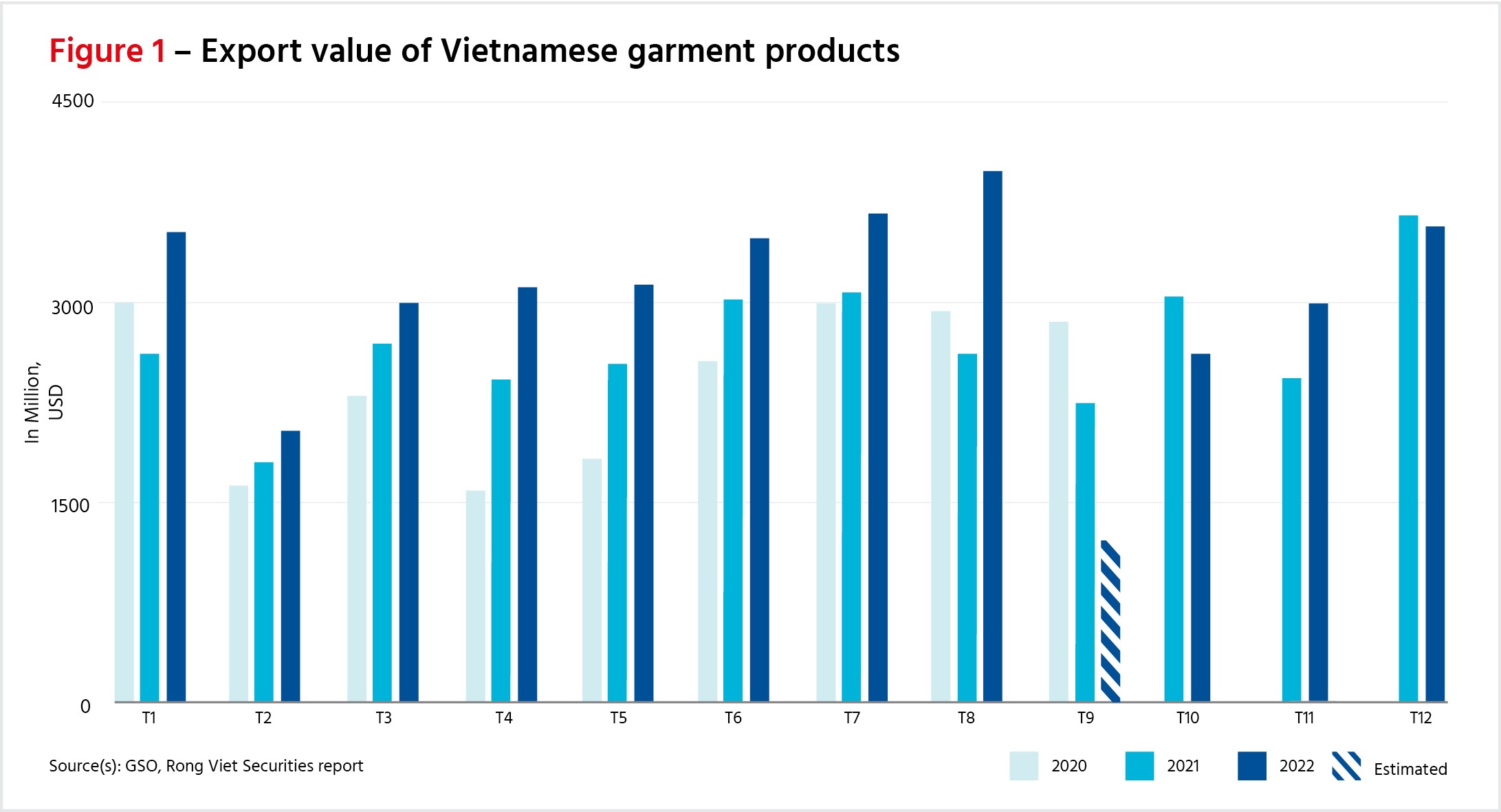

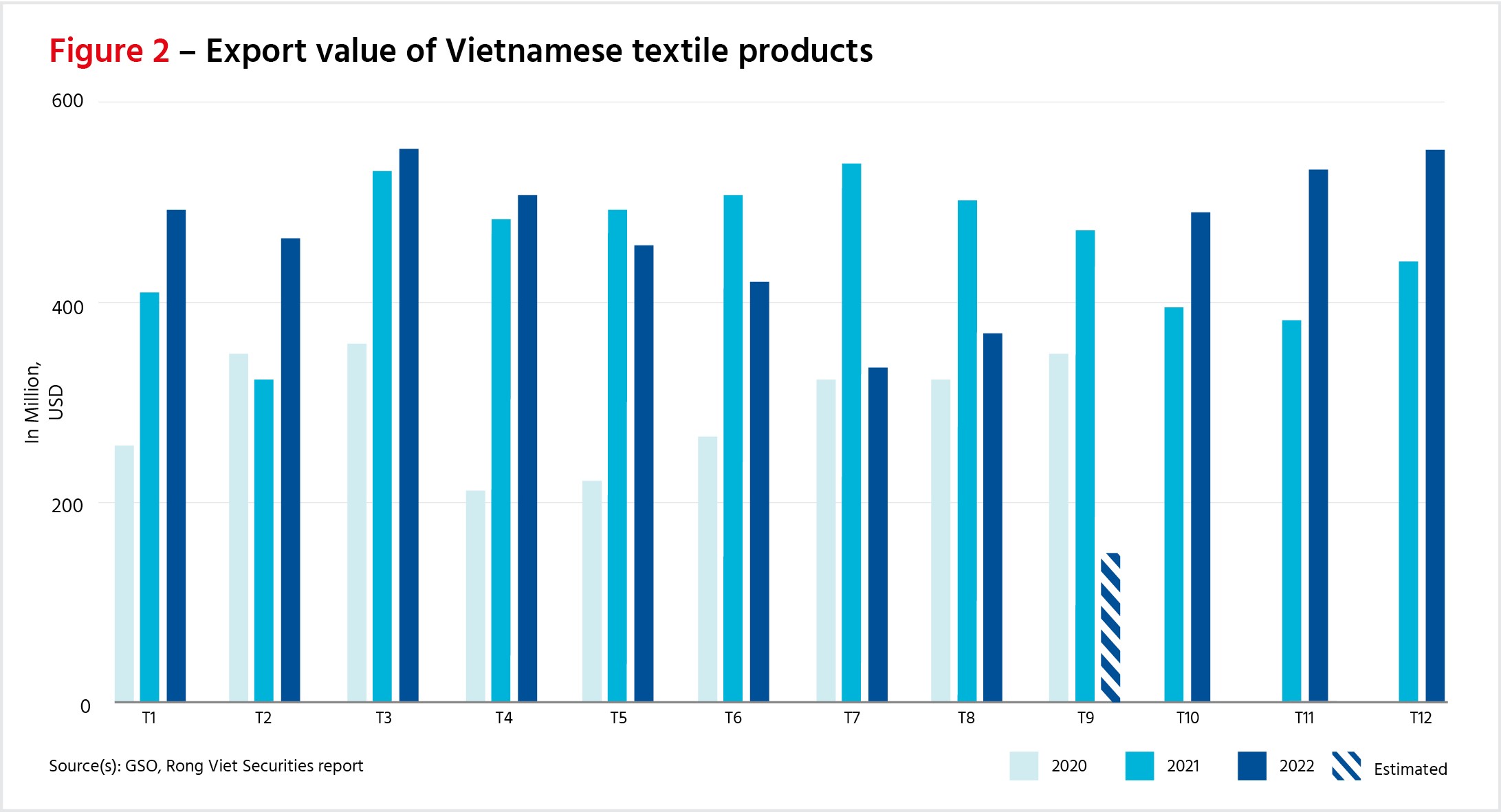

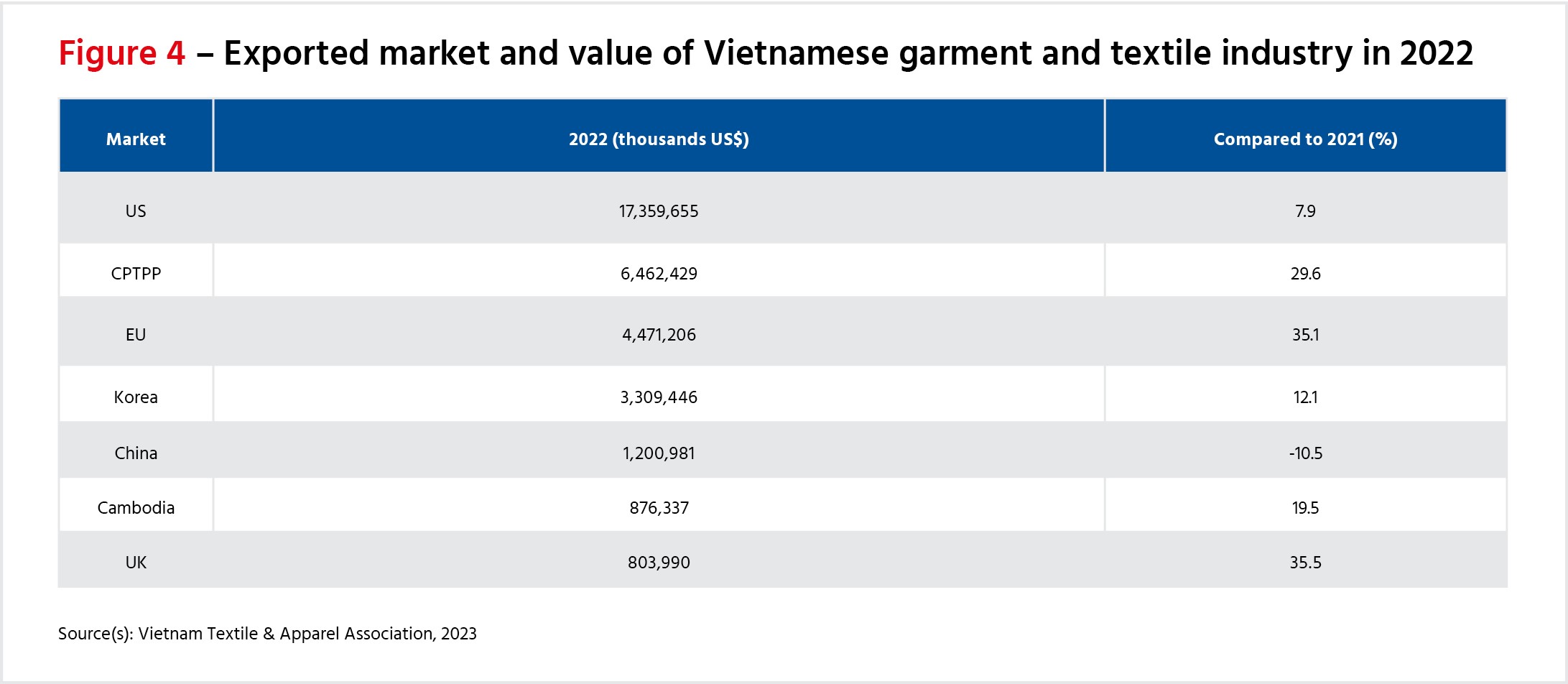

The garment and textile industry, accounting for 12-16% 5 of Vietnam’s total export value, plays a crucial role in the national economic development. In the first ten months of 2022, the garment and textile industry exports totaled nearly US$37.5 billion, increasing 14.5% year-on-year.6 The industry exported to 66 nations and territories. The import value of the garment and textile materials of Vietnam reached US$13.4 billion in the first six months of 2022, increasing by 9.8% from 2021.7 In 2020, for the first time, Vietnam surpassed Bangladesh to become the second-largest garment and textile exporter in the world after China.8 Vietnam can use the capability of neighboring countries to develop a complete supply chain from the upstream stage of raw materials.

However, the world’s economy is expected to experience turbulence in the next few years. Vietnamese garment and textile businesses are facing fierce competition from major exporters to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) members, the US, and the EU – China, Bangladesh, Turkey, and India. The rules of origin from yarn and fabric onwards is a weak part of the industry because Vietnam must import up to 80% of fabrics for export. Meanwhile, importers of Vietnam's garments and textiles are mostly swanky and fastidious, with strict requirements on the traceability of raw materials in multiple parts.

The elimination of forced labor is a fundamental labor right established by several import partners including the US and the EU. For example, the elimination of forced labor is one of the four fundamental labor rights that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) members recently agreed to adopt and maintain in their laws and practices. Combating forced labor has also been identified by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Confederation of Employers (ACE) as the top priority as the region moves towards economic integration.9

Impact on garment and textile supply chains

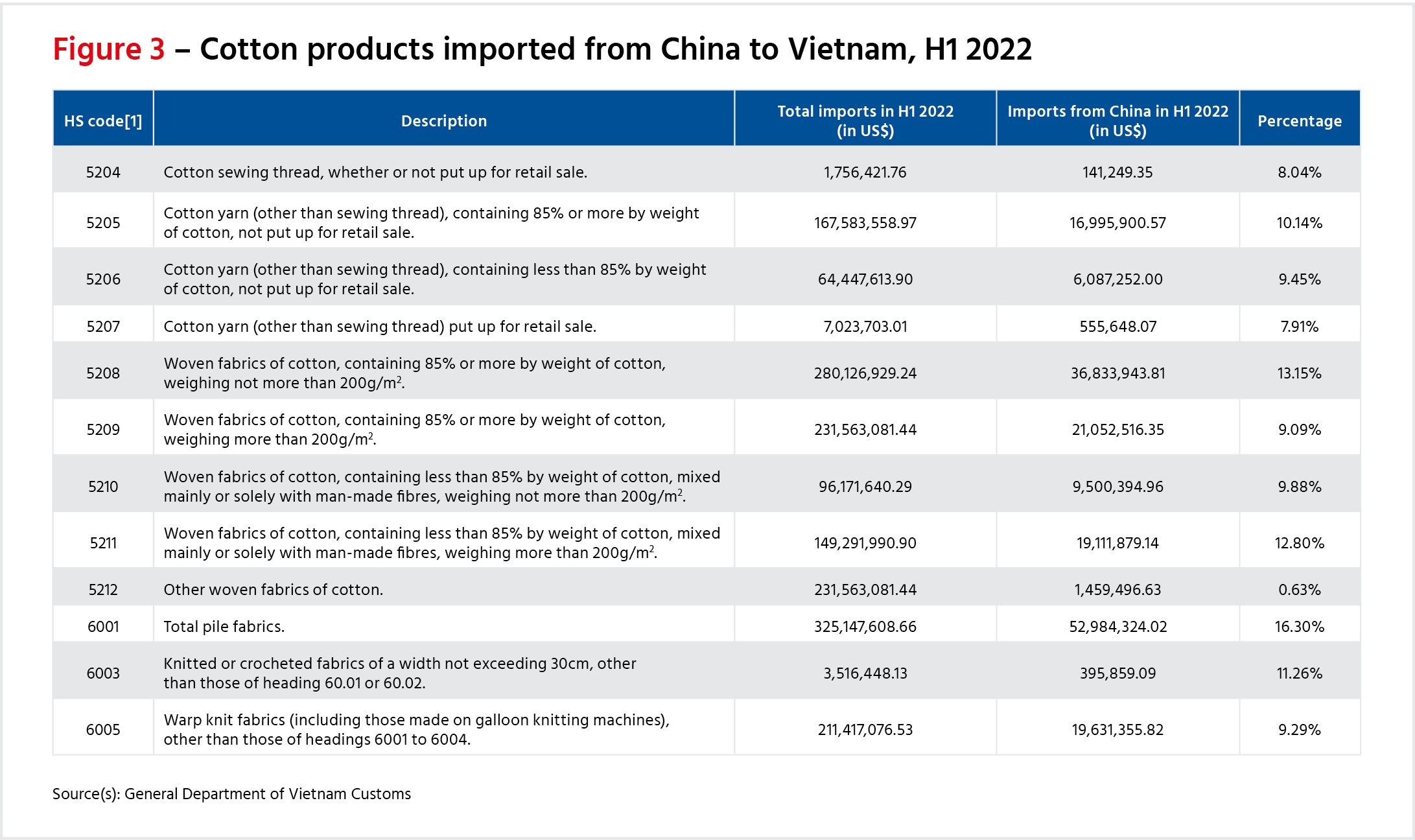

In December 2021, the US started enforcing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) to prohibit the import of goods wholly or in part mined, produced, or manufactured in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of China. Cotton is a major export of the XUAR, reaching markets around the world. Xinjiang cotton accounts for 84% of China’s exports of the product.10 According to the New York Times,11 raw cotton from XUAR is exported to 14 countries, including Vietnam, Thailand, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Meanwhile, yarn is exported to 190 countries.

In 2020, 52% of the imported cotton yarns and 61% of the imported cotton knits in Vietnam came from China. The table below shows the proportion of cotton products imported from China to Vietnam in the first half of 2022 (data from the General Department of Vietnam Customs).

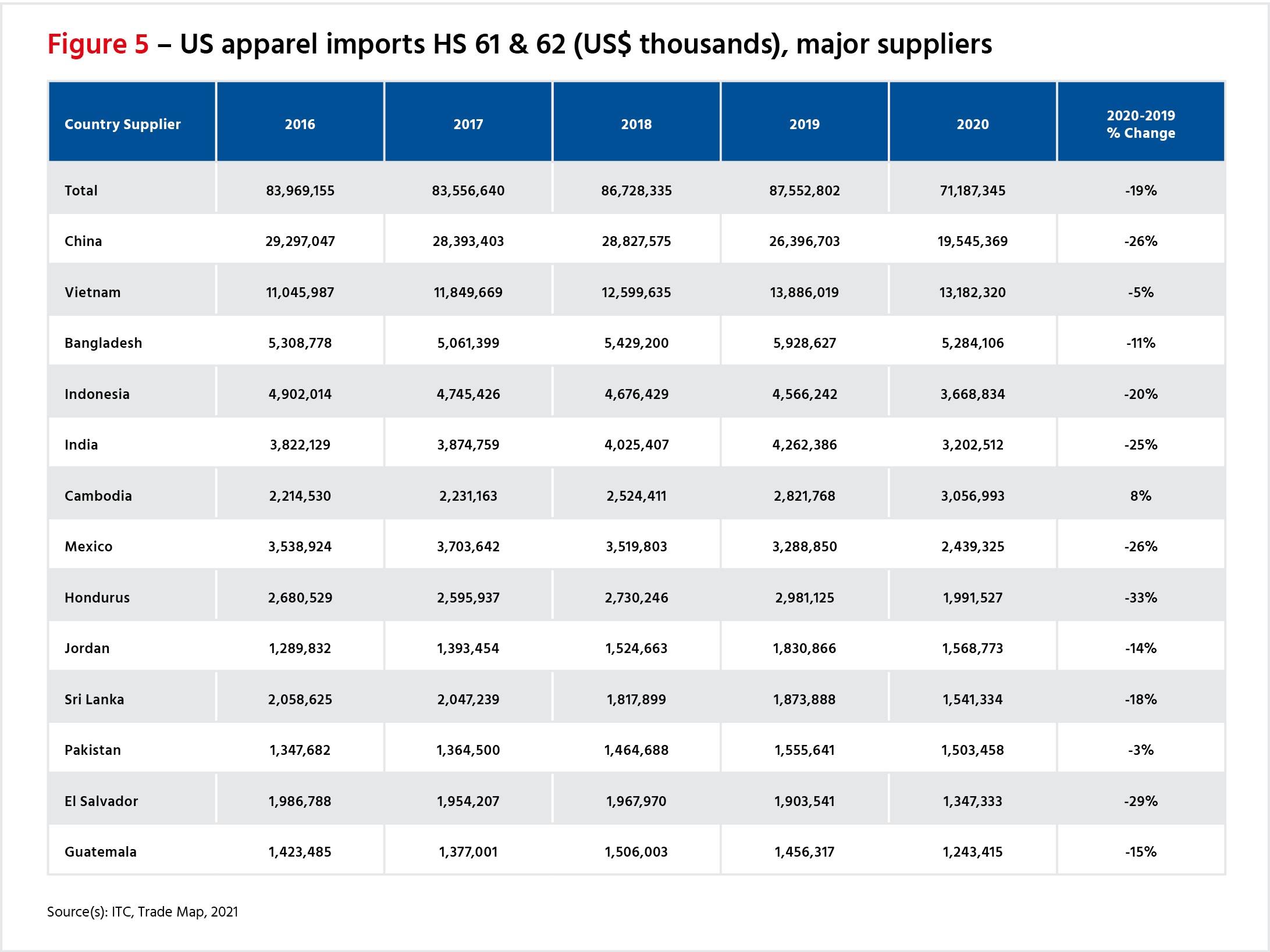

The Act threatens to cut Vietnamese producers off from the US market unless they can prove that Xinjiang cotton, or other apparel products, are not used in the production of their goods. Vietnamese firms will need to wean themselves off raw materials produced in China's Xinjiang region in order to ensure long-term access to the US market. Vietnam is the second largest apparel supplier of the US, and the US is the largest importing country of Vietnam’s garments and textiles (tables below). Thus, this Act has tremendously impacted the operations of Vietnamese firms in the industry.

Impact on internal business operations

Earlier this year, the EU Commissioner for Justice announced a new legislative initiative on mandatory human rights due diligence, expected to be tabled next year, as a follow-up to the EU Green Deal.14 EU companies and companies doing business with the EU, including Vietnam’s businesses, must put in place robust measures designed to identify and address human rights throughout the supply chains. Those companies have come under increasing scrutiny due to their failure to uphold labor rights.15 Labor exploitation and conditions in this female worker-dominated industry have been the research focus of several organizations like the Fair Wear Foundation.16 The issues identified raise questions about the role that regulations on human rights, due diligence, and supply chain transparency can play in mitigating the risks of exploitative working conditions and improving business accountability. Other instruments, such as trade agreements, can encourage adherence to labor rights standards. This is relevant in the context of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the EU and Vietnam.17

While Vietnam’s economy flourishes due to growing external trade, its human rights and sustainability practices are cause for concern.18 Political change in Vietnam has not been on par with its economic development. While Vietnamese labor laws are in existence to provide basic legal rights, Vietnam remains a one-party state intolerant of political dissent and freedom of expression.19 The independence of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and trade unions remains restricted, and crackdowns on labor and human rights activists are commonplace. For these reasons, a climate of fear dominates Vietnam’s civil society space.

Vietnam has seen significant improvements in legislation addressing forced and child labor in recent years although many adults and children are still at risk of labor exploitation. In 2016, Vietnam increased the national minimum monthly wage from approximately US$110 to approximately US$161.20 The last five years also saw the government implementing a wide range of decrees supplementing the labor code. These include Decree No. 85/2015/ND-CP21 providing several articles of the Labor Code relating to policies for female employees, and Decree No. 45/2013/ND-CP22 providing several articles of the Labor Code relating to working time, rest time, occupational safety, and occupational hygiene.

There has also been an increase in collaboration between the government and agencies such as the ILO and the EU on legislative reforms.23 The EU is particularly interested in seeing the ratification of the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work by the Vietnamese Government and is funding the ILO to assist with this effort.

The EU has also initiated a program on responsible value chains which will be implemented by the ILO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) focusing on the garment and textile sector in Vietnam. Other efforts include a nationwide complaints mechanism for workers by Fair Wear Foundation (FWF); a non-profit organization that works with brands, factories, trade unions, NGOs, and sometimes the government, to verify and improve workplace conditions for garment workers, and eliminate risks of forced labor. Better Work Vietnam, a partnership between the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, has been underway since 2009. Better Work Vietnam24 engages workers, employers, and governments to improve labor conditions in Vietnam’s garment sector and boost the economic competitiveness of the garment industry in Vietnam. It operates on the understanding that collaboration with national government bodies is essential to creating effective labor regulations for a sustainable impact.

Some other local NGOs also play a crucial role in eliminating forced and child labor in Vietnam. Notable efforts by organizations like the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation,25 Life Centre,26 and Pacific Links Foundation27 are important in creating awareness of the issues of labor exploitation. Services provided, such as educational opportunities, and shelters, as well as reintegration programs for trafficked women and children, also serve as a prevention tool for the re-victimization of forced and child labor survivors. While these efforts are commendable and ongoing, observations show that there is a tight grip on both local and international NGOs in Vietnam. They are not allowed to operate beyond what is mandated by the Government of Vietnam. For fear of losing access to factories, local and international NGOs have no choice but to carry out specific donor-driven, government-approved activities within factory settings. This restricts the much-needed labor rights interventions from which workers can benefit. They cannot provide full support or perform well enough as they can in other countries or regions like the EU, Singapore, or the US.

***

[1] Preventing forced labour in the textile and garment supply chains in Viet Nam, ILO:

[2] Vietnam-EU Free Trade Agreement

[3] Full text of CPTPP

[4] ASEAN Confederation of Employees

[5] VITAS monthly newsletter – volume 06 – June 2022

[6] Vietnam's textiles, garments export up 14.5 pct in 2022, Xinhua

[7] VIRAC - TEXTILE AND GARMENT MARKET IN THE FIRST 6 MONTHS OF 2022

[8] Vietnam surpasses Bangladesh as world's second-largest garment exporter Vietnam Investment Review

[9] Ibid

[10] US ban on cotton from forced Uyghur labour comes into force, Guardian

[11]Global Brands Find It Hard to Untangle Themselves From Xinjiang Cotton, The New York Times

[12] http://www.vietnamtextile.org.vn/ban-tin-thang_p1_1-1_2-1_3-199_4-681.html

[13] Trade statistics for international business development, ITC

[14] EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, European Commission

[15] Proposal for a regulation on prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market, European Commission

[16] Fair Wear Foundation

[17] FTA between Vietnam and the EU

[18] Ibid

[19] Refworld | Vietnam: The Silencing of Dissent

[20] A rapid assessment of labour conditions in Vietnam’s garment sector, antislavery.org

[21] Decree No. 85/2015/ND-CP

[22] Decree No. 45/2013/ND-CP: Decree No. 45/2013/ND-CP of May 10, 2013

[23] ILO and Viet Nam collaboration: ILO, Viet Nam strengthen cooperation on jobs, labour and social protection

[24] Better Work Vietnam

[25] Blue Dragon Children's Foundation

[26] TRANG CHỦ - LIFE

[27] Pacific Links Foundation – Building Resilience

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).