Published 21 September 2021

With the proliferation of government clean energy mandates, the projected need for lithium batteries has companies racing to secure raw and processed lithium for increased battery production in their home markets. Trade policies play a key role in ensuring steady supply, and whether countries can accelerate their green energy goals.

The near ubiquity of smartphones, tablets, and laptops, as well as modern conveniences like cordless power tools has fueled extraordinary demand over the last decade for lithium-ion batteries to keep all these devices reliably charged and re-charged. With the proliferation of government clean energy mandates, the rapid expansion of the electric vehicle (EV) industry is expected to drive lithium demand for the next couple of decades.

Often called “the new oil,” the projected need for lithium batteries has companies racing to secure raw and processed lithium for increased battery production in their home markets. The field is getting more crowded as dozens of new projects come online and deals are struck to become the favored supplier to auto manufacturers in major EV markets. For example, GM and Tesla recently announced plans to build their own high-capacity battery manufacturing plants in their home markets.

Essential for electric vehicles

Many governments have been touting ambitious plans to decarbonize their economies through electrification of public transportation systems and personal vehicles. Electric vehicles rely on lithium-ion batteries. If analysts’ predictions come true that batteries overtake internal combustion engines as the dominant power source for cars and trucks, then much more lithium will be needed in the next decade. For example, one Tesla Model S uses 140 pounds of lithium, roughly the same amount as in 10,000 cell phones.[1]

Lithium producers are reluctant, however, to ramp up too quickly. EV expansion has come in fits and starts, as demand for EV vehicles remains reliant on government subsidies and incentives. When lithium prices rose in response to the demand associated with the first wave of EV growth between 2015 and 2018, lithium producers responded by increasing output threefold, according to the US Geological Survey.[2] But excess production sent lithium prices plummeting to around 80%. Lower profits sent mining company stocks tumbling too. Subsequently, lithium producers reduced their output in 2020.[3]

Demand is rising again. Indeed, 2021 could be a tipping point when orders for lithium begin to exceed supply, according to analysis by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. The question is how quickly existing lithium producers choose to develop additional resources through unused or new capacity.

The lithium battery value chain has also become a chess board in government industrial policies. Governments in major lithium extracting countries are no longer satisfied to sell to Asia where the batteries are made. Instead, countries that seek to expand their EV markets are imposing trade restrictions to incentivize more battery production at home.

A handful of large operations

Commercial lithium is generally derived from two major sources: underground brine deposits and mineral ore deposits. Most lithium production is attributed to just a handful of large operations: five mineral operations located in Australia, two brine operations in Argentina and Chile, and two brine and one mineral operation in China.[4]

With technology and automotive companies fighting over supplies, and other countries sitting on

significant reserves and resources, new lithium projects are proliferating. The countries venturing into lithium are a diverse set and include Bolivia, the United States, Austria, Canada, Finland, Namibia, Portugal, Serbia, Spain, and Zimbabwe. Thirty-nine active mining projects are being developed in North America alone.[5]

The uptick in lithium projects reflects the perceived need of lithium buyers to pursue a two-pronged strategy. The first task is to diversify their sources for materials. Secondly, buyers are looking to acquire the capability to produce both intermediate lithium compounds and the finished battery packs – to serve fast-growing EV markets.

Trade policies can ease access

Trade policies play a key role in where companies locate lithium battery production.

For example, the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement introduced highly restrictive rules of origin. By 2023, North American vehicle manufacturers will have to certify that 75% of their components are locally produced. [6] To meet these requirements, US manufacturers will have to reduce their reliance on lithium-ion batteries exported from Asia.

To avoid Trump-era tariffs on batteries from China that will remain in place indefinitely, EV manufacturers are also incentivized to produce batteries in the United States.

Tariffs remain in many markets. Under the WTO Information Technology Agreement 2, China had demanded batteries be excluded from tariff elimination in order to build up domestic production to support home-grown EV manufacturers. To meet demand in its own EV market, the Chinese government has now lifted restrictions on foreign ownership of EV battery manufacturing plants within China.[7] However, it will retain a 10% import tariff.

Governments in other high-growth EV markets are also adjusting their strategies. For example, the Indian Government is contemplating raising its tariffs on batteries from China to mitigate a 300% spike in imports in recent years. India is also encouraging local battery production based on technologies that leverage abundant domestic resources such as bauxite.

For the time being, trade policies around lithium batteries remain designed to reduce imports, whereas tariff liberalization could help stabilize access as demand for lithium rises.

The center of global lithium trade

The Chinese government subsidizes both battery and EV production as a matter of industrial policy. By 2018, Chinese companies produced more than 60% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries.[8] To become the world’s supplier of batteries, China had to become the world’s largest global importer of raw lithium minerals. These dynamics put China at the center of global lithium trade.

Foreign sellers of raw lithium want to reduce dependence on China as a buyer. Foreign buyers of batteries are concerned they should reduce their dependence on sales from China.

For its part, the Chinese government is taking steps to aggressively expand lithium extraction within China to serve its growing needs and reduce its reliance on imports of lithium from Australia and Chile. As domestic extraction will not be adequate, the government is also supporting plans by Chinese lithium processors to acquire equity in the world’s largest mines outside China. Notable deals include a 51% stake in Australia’s Greenbushes mine, a 23.8% stake in Chile’s SQM, and a 50% stake in the Cauchari-Olaroz brine operation in Argentina.[9]

Australia and Chile attempt to move up the value chain

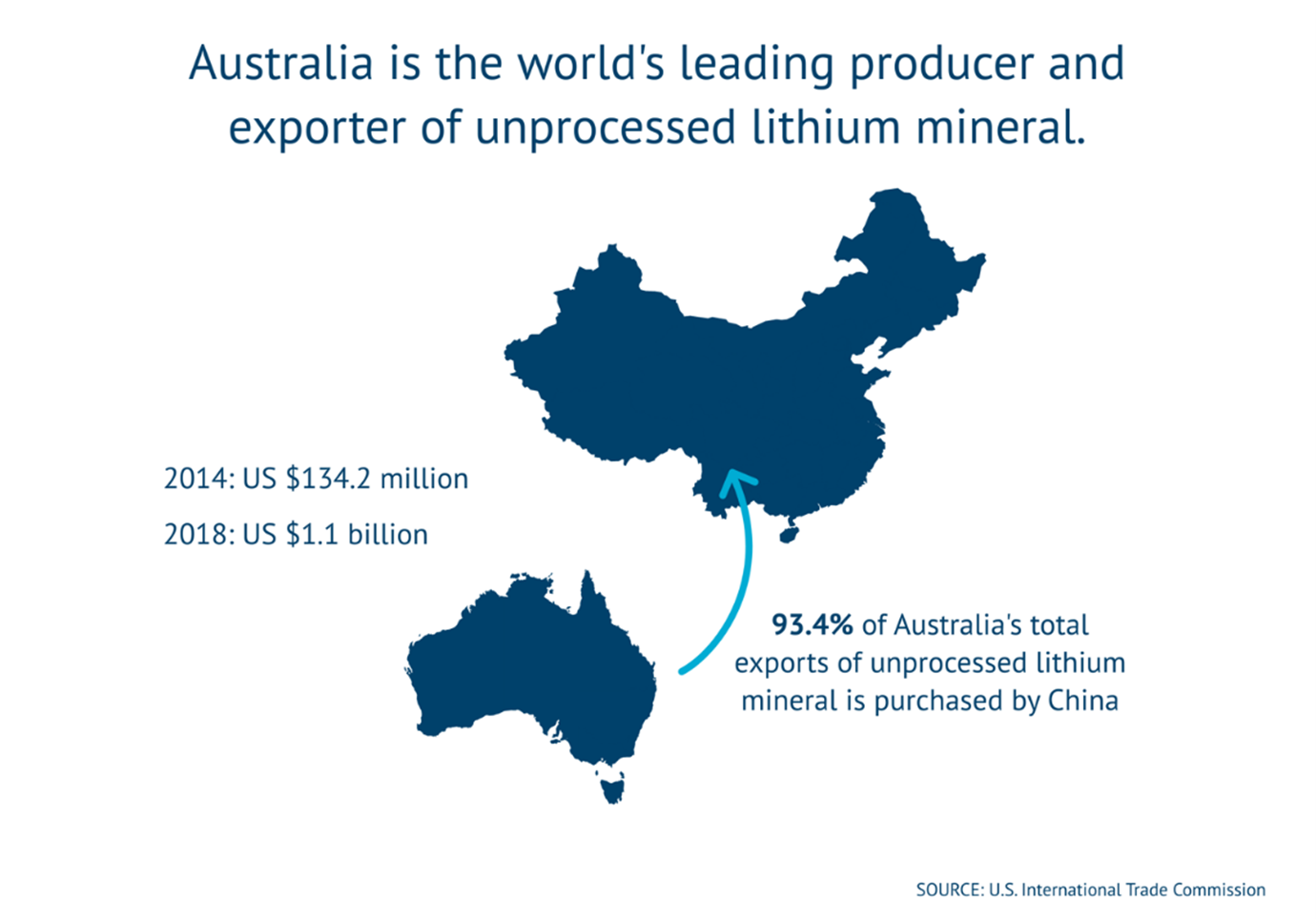

While China refocuses upstream, the Australian and Chilean governments are focused on downstream capabilities. Supplying 60% of the world’s lithium, Australia has become dependent on buyers in China that process lithium into the compounds used in battery production.[10]

Most of the world’s remaining lithium supply comes from brining operations which are primarily in Chile. Brine concentrates tend to be processed into lithium carbonate at the source, so Chile is a major supplier of processed lithium carbonate and hydroxide, which are precursors to the lithium used in battery production. If Australia is dependent on China as a buyer, Chile is dependent on two countries: South Korea and Japan. More than half of Chile’s lithium chemical exports go to battery producers in the North Asian countries.[11]

In recent years, the Chilean government developed a scheme to promote local processing. Companies that agree to process lithium and produce batteries in Chile will be eligible to buy up to 25% of lithium production at special prices.[12] Companies from Russia, China, Belgium, and South Korea participated in the government’s first auction, alongside Chilean companies.

As the European Commission prefers to promote battery production inside the EU, it is locking in lower priced exports of Chilean lithium through the updating of its 20-year-old trade agreement with Chile.

The Australian government introduced tax offsets to incentivize chemical processing and battery cell production for export tariff-free under its free trade agreements, for example to the United States, thereby setting itself up to compete with China’s battery exports.

The lithium market is dynamic and changing as companies and governments shore up the reliability of their sourcing. Trade policies play a key role in shaping the market and will become more important as the next generation of lithium batteries comes online.

Cobalt is a key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries, but its extraction is concentrated in a single country: Democratic Republic of Congo. Concerned about the reliability of supply from Congo, researchers around the world have accelerated the development of future battery chemistries that minimize or even replace cobalt altogether.[13] Cobalt-free lithium batteries and other forms of lithium-metal batteries are likely to underpin even higher demand for lithium resources, providing more impetus for countries to invest in domestic production and diversify away from reliance on China.

Lithium is enabling countries to accelerate efforts to electrify their transportation sectors and work toward their green energy goals. The question is whether trade policies will become more restrictive or whether governments will agree that removing barriers to trade is the best way to assure supply.

_________________________

[1] - National Geographic, February 2019

[2] - U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2021

[3] - Ibid

[4] - Ibid

[5] - S&P Global Market Intelligence, Data compiled March 2021

[6] - United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Chapter 4 Rules of Origin, Appendix Provisions Related to the Product-Specific Rules of Origin for Automotive Goods accessible at ustr.gov

[7] - https://www.xinbailaw.com/en/insights-and-publications/foreign-ownership-restriction-on-electric-vehicle-power-battery.pdf

[8] - U.S. International Trade Commission, Global Value Chains: Lithium in Lithium-ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/working_papers/no_id_069_gvc_lithium-ion_batteries_electric_vehicles_final_compliant.pdf

[9] - Ibid

[10] - Ibid

[11] - Ibid

[12] - Driving Demand: Assessing the impacts and opportunities of the electric vehicle revolution on cobalt and lithium raw material production and trade, International Institute for Sustainable Development report July 2021. https://www.iisd.org/publications/electric-vehicle-cobalt-lithium-production-trade

[13] Ibid

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).