Trade distortion and protectionism

Non-tariff barriers and the mystery of UK food price inflation

Published 14 March 2023

A recent study shows that the impact of non-tariff barriers on food prices in the UK post-Brexit only led to a small loss in economic welfare. Surprisingly, British food prices have increased less quickly than those in the EU despite tighter market access. There are multiple factors at play, not least the Ukraine war, the Covid-19 pandemic, and new competition introduced to the British market.

In mid-2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. As it turned out, this also meant leaving the European Single Market and the Customs Union. Consequently, despite a reasonably deep free trade agreement, the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), which guaranteed tariff-free and quota-free trade between the UK and the EU, non-tariff barriers to trade (NTBs) increased. These are barriers that don’t involve duties, including quotas and customs checks.

These new NTBs are probably most pronounced in food and agricultural trade, where sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) checks can create considerable costs, and customs clearance procedures create paperwork. The World Bank estimates that NTBs to trade are the highest in the food sector although there is considerable variation among products.[1]

Brexit and rising food prices

The UK is a big net food importer, producing about 65% of the food it requires. Because it also exports some food, imports account for about 45% of total food consumption.[2] The EU has always been the major source of UK food imports. This may not be surprising, given the UK’s erstwhile membership of the European Single Market (and therefore lack of NTBs), the EU’s production of surplus food, the relatively high NTBs and tariffs for non-EU producers, and the geographic proximity of continental Europe to the UK. In 2015, prior to the referendum, about 69% (by volume and value) of UK food imports came from the EU.[3]

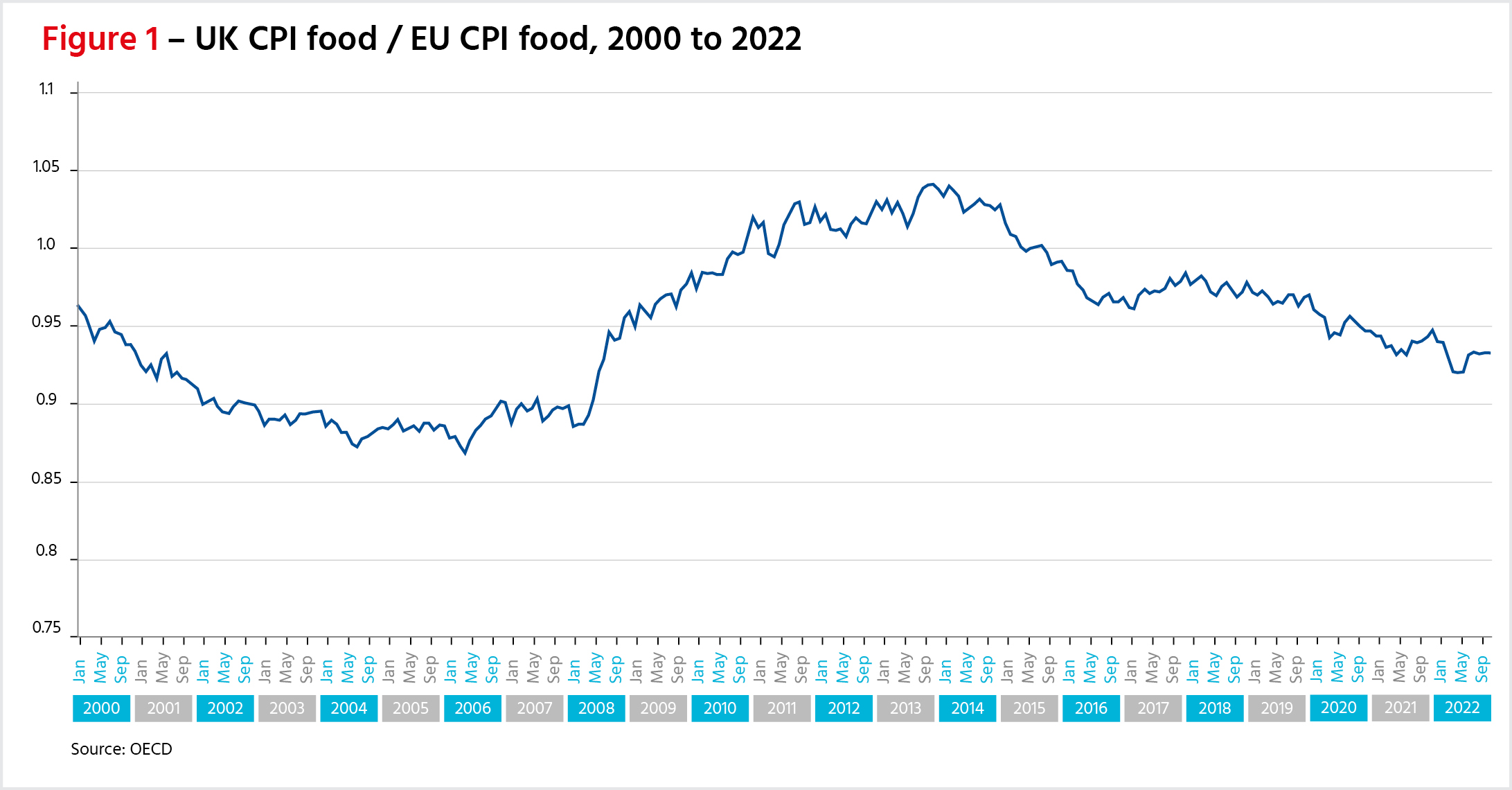

It would seem that the introduction of new trade friction in the form of NTBs resulting from Brexit, might increase UK food prices relative to EU food prices. However, this has not been the case by and large. The chart below shows Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development data for food for the UK divided by food for the EU, categorized by those food items used to calculate consumer price inflation. When the line is rising, UK food prices are rising faster than EU prices, and vice versa.

Whether one makes the calculation based on the date of the referendum, the official departure date of the UK from the EU, or the end of the transition agreement, UK food prices have lagged those in the EU by between one and three percentage points. What makes this particularly remarkable is that sterling weakened substantially both prior to, and especially after the referendum, which, given the UK is such a large food importer, would lead one to expect food prices to have increased faster than those on the continent. Hence, economists could be forgiven for expecting a double whammy of exchange rate-induced and trade friction-induced food inflation relative to that in the EU.

However, just because UK food prices have not increased faster than those on the continent, does not mean that NTBs have not affected inflation (or the exchange rate, for that matter). It simply means there have been offsetting and relatively deflationary impacts as well.

Impact of Non-Trade Barriers

A recent study by Jan David Bakker, et al.,[4] set out to isolate the impact of NTBs on consumer prices of food in the UK resulting from Brexit and to assess the subsequent loss of economic welfare. This paper is the subject of our podcast “Current Accounts”. The study used the global customs taxonomy’s Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System at the relatively detailed six-digit level for import data to determine investment flows and the level of EU import intensity across a range of food products. Import intensity here measures the share of UK imported input into a product that comes from the EU. By comparing price changes against the level of import intensity from the EU, researchers were able to discern a tendency for the more import-intensive products to rise in price faster than those with less EU import intensity. Of course, with domestic EU food prices rising faster than the UK, this would be expected anyway. However, researchers also detected a tendency for those products with high NTBs to increase faster than those with low NTBs, indicating that NTBs may have indeed had an impact on food prices in the UK.

Surprisingly perhaps, the study found only a small loss of economic welfare. During two years of study, the authors found that deadweight loss resulting from higher prices and lower volumes amounted to just more than GBP1 billion (about GBP500m per year). For context, annual GDP in the UK in 2020 and 2021 averaged about GBP2.2 trillion, so the welfare losses amounted to about 0.02% of GDP. There was however a considerable transfer of welfare within the UK from consumers to UK producers, with consumer welfare falling by GBP5.8 billion and producer welfare rising by GBP4.8 billion.

The study found that UK food prices for products with average import exposure to EU imports (75% on their numbers using 2015 weightings) rose by 8% over two years relative to products with zero EU import exposure. Furthermore, products with low NTBs showed no statistically significant price increase, relative to non-EU imported product groups while the high NTB categories accounted for the entire change.

The study has intuitive appeal but, if its findings are correct and the quantification of them is in the right ballpark, how can we explain that UK food prices have increased less quickly, not more quickly, than those in the EU despite the tighter market access?

Perhaps the study highlights the limitations of economic “event studies” where the event being tested coincides with a period of considerable disruption caused by other events—in this case the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. EU food producers have been hit hard by rising gas; and therefore, fertilizer prices. The EU has experienced significantly higher food price inflation due to its energy strategy, and the consequent European gas premium, than the United States, Australia, or Canada. The EU has lost market share in the UK food market partly due to its loss of competitiveness resulting from higher input costs and partly because EU producers now face a level playing field with other zero-tariff and zero-quota countries. According to the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the EU has lost 8 percentage points of share in UK imports since the referendum,[5] but the study used fixed EU import intensity weights set in 2015, prior to the referendum. The EU remains the dominant source of UK food imports.

In addition, on leaving the Customs Union, the UK launched its own Global Tariff schedule which, at the margin, reduced import tariffs on food. The UK now also has its own Generalized System of Preferences. The changes in these though seem minor in comparison to the gap in observed relative UK-EU food price inflation when compared to the deduced impact of new NTBs. Furthermore, perhaps food exporters outside the EU now see the UK market as being worth pursuing in ways they did not, while the UK was an EU member state, thus increasing competition.

Externalities and confounding factors

Important as some of these factors might be, they do not appear to explain all the approximate 10% difference between the observable reality of UK-EU relative food price movements and the price changes that were intuitively expected, even ignoring the exchange rate impact.

One possibility is that the NTBs for imports into the UK have decreased across the board. SPS testing has been phased in with some measure yet to take effect,[6] while investment in new customs infrastructure may have reduced trade friction with non-EU partners. Furthermore, underlying inflationary pressure from costs may have been absorbed by companies in the form of margin compression. Whatever the correct explanation, UK consumers have not faced higher aggregate levels of food prices than their EU counterparts since the enactment of the TCA.

Two broad conclusions with global applicability can be drawn from this analysis: first, the distributional effects of barriers to trade may be significantly larger than the overall welfare gains and losses. In this particular case, the distribution of welfare from consumers to producers is about five times larger than the overall welfare loss. A second possible conclusion is that where NTBs exist, if their rationale is protectionism and limited market access, they can be very significant. However when importers wish to diminish trade friction, they may shrink substantially in potency. In other words, the severity of the trade friction is dependent on the attitude with which measures are applied as much as by the measures themselves.

***

[1] See: Bakker et al : dp1888.pdf (lse.ac.uk)

[2] UK food security report 2021.

[3] UK food security report 2021.

[4] dp1888.pdf (lse.ac.uk)

[5] UK food security report 2021 page 94

[6] https://www.customs-link.com/blog/prepare-new-2023-eu-uk-sanitary-and-phytosanitary-controls-updated

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).