Trade and geopolitics

A wake-up call: China threatens a solar trade embargo

Published 21 March 2023

China's recent proposal to introduce export controls on more than 100 technologies, including solar panel components, could imperil Europe's decarbonization goals, analysts at the think tank MERICS say in an article for the Hinrich Foundation. While the weaponization of solar trade would be undesirable for both the EU and China, Beijing is clearly moving to develop a policy toolset to create bargaining chips amid rising global trade and geopolitical tensions.

As the United States dials up efforts to block China’s access to critical high-tech for defense-enhancing technologies, the Chinese commerce and technology ministries have in recent months responded by publishing a proposal to introduce export controls and bans on more than 100 technologies, including tech to process silicon wafers, a key component for manufacturing photo voltaic (PV) cells for solar panels.

This comes at a sensitive time, as European governments are struggling to diversify energy sources away from fossil fuels, not least following the abrupt exit of Russian gas, and to alleviate high dependencies on critical technologies from suppliers outside the European Union. While the PV technology in question is listed in the category “export-restricted,” not banned, the bill would give Beijing a formal instrument to administratively control exports of such components, including potentially barring exports to any partner. While the policy has not been finalized, the fact that it was published to elicit public opinion is an indication that the proposal has reached near-final stages within the bureaucracy and is likely to be adopted soon.[1]

At the National People’s Congress, China’s highest-level annual legislative conclave, President Xi Jinping reiterated the need to develop technological independence, boost domestic manufacturing capabilities, and “occupy the commanding heights of the global new energy industry.”[2] At the same time, leaders in Beijing are increasingly critical of Western moves to restrict Chinese access to technology, and are calling to develop stronger “long-arm jurisdiction,” a term used for trade instruments and other means of “law-fare” capabilities—meaning the strategic use of legal proceedings—to protect and assert national interests globally.

The threat puts Europe in a bind: If the continent responds by cutting out Chinese imports of green technology too quickly, it would set back Brussels’ decarbonization targets, and make them significantly more expensive. Even optimistic accounts estimate investments to be hundreds of billions of dollars to rebuild a PV supply chain outside China.[3] On the other hand, Beijing is beginning to develop instruments that enable it to flex its muscles in a more targeted way, and Europe should be prepared.

Given the rising global contest in the technology space, Beijing likely will be tempted to use its leverage over technology and supply chains more actively in the future. In an increasingly confrontational geopolitical environment, Beijing is working hard to develop a localized technological base that it can weaponize, including for non-sensitive technologies.

Green tech exports restrictions and decarbonization

In the larger economic picture, PV export restrictions would not severely set back the global economy, or broad economies of targeted markets, in the short to medium term. However, decarbonization plans would be severely affected. In other words, a solar panel shortage would not result in the kind of deep and wide-ranging economy-wide consequences of having one’s main energy provider suddenly cut off, as Europe experienced with Russia. Neither would it harm long-term innovation in targeted economies to develop advanced technologies, unlike the November 2022 US measures to hobble China’s ability to manufacture and acquire high-tech defense-related capabilities. From an economic security perspective, there is no urge to limit cooperation with Chinese PV companies as a response to Beijing’s new threat.[4]

However, Europe’s ambitious climate targets and the necessary energy transition make limited access to green energy equipment a sore spot. Most developed economies have adopted decarbonization targets, and plan to aggressively expand solar energy as part of their energy transition. Following the abrupt shift away from Russian gas, and increasingly costly fossil fuels, European planners are increasingly nervous about their substantial dependence on Chinese energy technology and components.

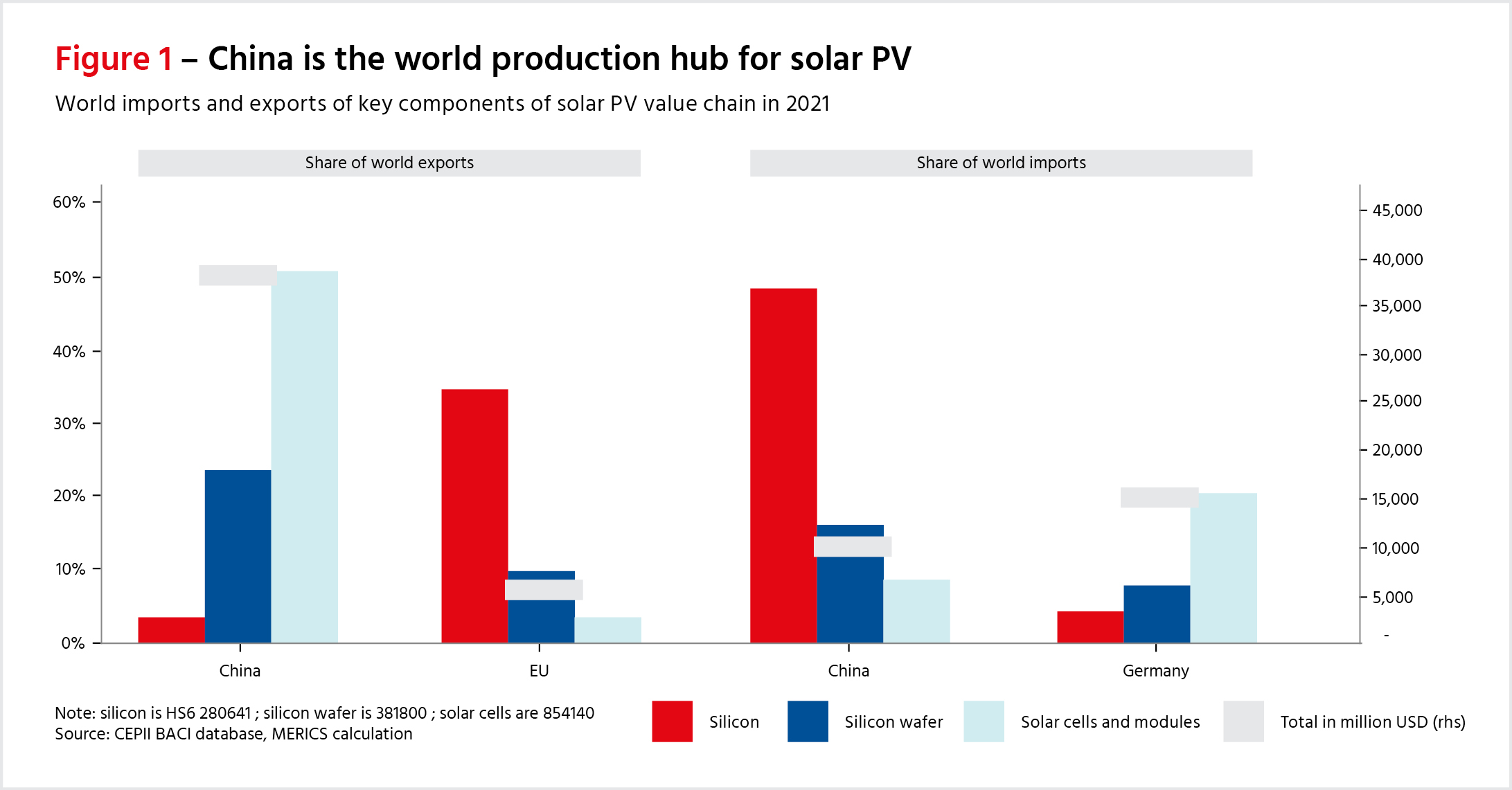

China dominates the global PV supply chain, making up more than 50% of solar PV exports, and about the same share of imports of raw silicon (see Exhibit 1). In terms of industrial capacity, the footprint is even more striking given that the European market is the biggest one for Chinese producers, supplying more than 90% of the world’s wafer production.[5] Global demand is vast and growing, and few alternatives to Chinese exports exist in the near term.[6] Chinese signals to limit the supply of PV, the cheapest renewable energy, are thus stoking fears about Beijing’s future plans to weaponize technology critical for energy diversification and decarbonization.

Without Chinese PV, Europe cannot make its energy decarbonization targets. Even if markets move to substitute solar with other renewables, these other renewables also have large parts of their supply chains located in China. As the US and the EU double down on green energy, including ambitions to develop local production, and undertake ongoing bilateral and structured cooperation talks, China’s draft bill is heating up the debate abroad over the need for diversification away from Chinese suppliers.

Proposed restrictions likely to focus on targeted licensing, rather than broad bans

More generally, for global climate action, and from a narrower business perspective, Chinese export controls would be a poor decision. The world has benefited greatly from cheap PV made in China. Chinese PV production costs are 35% less than the EU and 20% less than US producers, and PV is (together with onshore wind) now the cheapest power source. Climate action benefits from globalized low-carbon value chains, and recent estimates put savings for PV installers at around US$67 billion in China, Germany, and the US.[7]

Granted, those costs have come down in part because of massive subsidization and localization by Beijing, contributing to a greater concentration of production in China. This strategy led to China’s dominance in the field, and the rapid downscaling of PV production in Europe.[8]

Nevertheless, China made solar widely available globally, and both export controls and supply chain diversification will mean increasing the cost of decarbonizing global energy systems for years to come. Neither the EU nor the US have production capacities anywhere near the scale needed to meet their climate targets and energy transition plans without Chinese imports.

Reacting rashly by swiftly winding down European PV trade with China makes decarbonizing energy systems very costly at best, and potentially impossible in the decade to come. If anything, everyone—including China—needs to ramp up production, as global capacity must quadruple to attain net zero carbon emissions around 2050, according to the International Energy Agency.

But limiting exports is not economically beneficial for China. PV exports are valued at around US$30 billion and made up more than 6.5% of China’s annual export surplus in recent years. This means that, in the event of PV export controls, Beijing would inflict large losses on Chinese firms, which are currently betting on rising exports and ramping up capacities. Worse yet for Beijing, any prospect of export restrictions is likely to lead to losses in global market share for its companies and spark the development of long-term competitors globally. Many in Washington and Brussels are already pushing hard for such restrictions. This is a policy consequence the Chinese already should be quite aware of, given its previous weaponization of global trade dependencies, such as for rare earth. Therefore, the mulled bill is most likely created primarily for targeted restrictions and licensing, rather than broad bans upending China’s position in the supply chain.

A perceptive response

China sees itself confronted with an increasingly antagonistic environment in several sectors. Trade restrictions and export controls by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries are on the rise, and debate in developed economies about diversification away from China is gaining traction. China is mulling how to react. Clearly, Beijing has calculated that green tech and decarbonization are strategic areas in which it might have leverage over foreign policymakers. PV is a sector in which China has consolidated a huge concentration in global supply. Given global energy transition plans and the Russian gas shock to Europe, picking the PV sector for potential export controls underscores how China is beginning to leverage its advantages in global trade and technology more overtly.

As the EU and the US accelerate industrial and localization ambitions on solar panels, it makes sense for China to develop its own policy instruments to protect intellectual property for made-in-China technology. Policy tools to administer exports, including licensing, restrictions, and localization requirements, are relatively new to China, but solar could be just the first in a long list of technologies to be put under tighter scrutiny by Beijing as China’s industries move up the value chain.

Policymakers in the West should recognize that China is starting to gain an advantage in key components of cutting-edge technology, specifically in energy and green tech. A recent report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute underscores this, stating that China “is further ahead in more areas than has been realized” in hosting, nurturing, and owning critical technologies including robotics and biotech.[9] President Xi Jinping has set “global leadership” in new energy and high technology as a key goal. The investments and vast resources pooled towards boosting the industry around domestic technology are just beginning to pay off.

Given the difficulties of the EU green transition and the economic costs to Beijing of constraining Chinese solar component exports, a tit-for-tat escalation appears avoidable for now.

But this does not mean the West doesn't need diversification; Europe and the US would benefit from building more capacities at home. Every megawatt of PV production capacity creates more than 1,000 jobs, according to the IEA. Diversifying away from subsidized Chinese firms could also spark long-term gains in innovation. Policymakers must expect a reaction from China. This also applies to other policy measures, including those aimed at eradicating forced labor or subsidies, that have strong potential implications for Chinese solar equipment exports.

Mid-term, Europe shouldn’t panic over China’s mulling of such a bill. It is unlikely Beijing will fully weaponize a highly profitable growth industry, one in which it actively seeks to become a global leader. This would undermine China’s immediate economic interests. It should rather be seen as part of the ongoing efforts to develop a policy toolset that equips China to act a wider range of levers when it comes to global trade and technology tensions, amid increasingly politicized markets and supply chains. The proposed bill shows that Beijing is crafting bargaining chips in this space for the future.

In the important and necessary discussion on how to decrease Europe’s dependence on large single markets for essential goods and technology, a realistic assessment of cost and substitution is vital. Compared with replacing the high concentration in China of the global PV value chain, weaning Germany off Russian gas was easy. Until capacities are built in Europe, few alternatives to Chinese supply exists. The upside might be that fears of China developing export controls on solar (and other green tech), would accelerate the discussion in the West on such diversification. Fostering European and American diversification away from China is a scenario Beijing wants to avoid, but which has genuine long-term benefits for Europe. Given the side effects of weaponizing supply demonstrated a decade ago with Chinese restrictions on rare-earth exports to Japan, policymakers in Washington, Brussels, and Beijing might consider tempering down their inclination for retaliatory weaponization of economic flows.

There are no easy solutions to Europe’s dependence on China save the unpalatable option of slowing down global decarbonization goals. Policymakers should learn from and act upon this threat. Unless the major actors in this global trade find an acceptable equilibrium, it would fast-track the fragmentation of globalization.

***

[1] Notice on Public Consultation on Updating the Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited or Restricted by China from Export

[2] 正确引导民营经济健康发展高质量发展 (people.com.cn)

[3] Reforging the Solar Photovoltaic Supply… | The Breakthrough Institute

[4] Risks of decoupling from China on low-carbon technologies | Science

[5] Solar PV Global Supply Chains – Analysis - IEA

[6] EU Commission

[7] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05316-6

[8] The Impact of China’s Production Surge on Innovation in the Global Solar Photovoltaics Industry | ITIF

[9] https://www.aspi.org.au/report/critical-technology-tracker

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).