Free trade agreements

ASEAN waits for RCEP ratification – and post-pandemic integration

Published 07 September 2021

Given the uncertainty surrounding Covid-19 variants and political instability in the region, the RCEP may not come into full force until 2022. As the free trade agreement seeks to transform existing global value chains, gaps in provisions and the increasingly inward-looking policies adopted by members could curtail the benefits brought by greater integration.

The signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2020 was a historic event, marking the formalization of the world’s largest trading bloc by GDP size. RCEP is also the second mega trade deal for the Asia Pacific region, after the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Even as the Covid-19 pandemic remained a sobering reality, RCEP signatories greeted the agreement with excitement.

Now, the wait. RCEP will only function when it comes into force with a minimum of nine member countries (six from ASEAN members and three from non-ASEAN economies) ratifying the agreement. Given the uncertainty surrounding Covid-19 variants and political instability in the region, the free trade agreement (FTA) may not come into force until 2022.

That gives RCEP members time to reflect on the potential of the FTA and its role in the future economy.

After all, a global malaise has set in, precipitated by the pandemic. Global demand has weakened, and trade tensions continue in the region and beyond. Many believe that RCEP is capable of reshaping and boosting the region’s existing framework for cooperation into a more committed and binding nature – and position the region for strong and regional integration.

Indeed, with the right policies in place – and more on that shortly – RCEP may be able to reinvigorate the regional economy. With the right policies in place, foreign investors would be attracted by the region’s prospects and commit more foreign direct investment (FDI), thus creating jobs and attracting international expertise. Investments in hi-tech industries will enable developing countries to benefit from anticipated technology and knowledge transfer. Higher productivity along the region’s supply chains will follow.

An alphabet soup of interdependencies

But first, the agreement must be ratified. Ratification is one of the biggest hurdles in any free trade agreement. FTAs typically require lawmakers and policymakers to introduce new laws or upgrade existing laws that align with the new commitments made – a process that is easier said than done.

RCEP was signed at the 2020 ASEAN Summit after eight years of negotiations. By then, the 10 ASEAN member states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam), and five of ASEAN’s existing plus-one partners (Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea) were proud to have forged an agreement.

Their achievement is significant. Collectively, RCEP’s 15 member countries represent an estimated GDP of US$25.8 trillion, or around 29% of global GDP.[1] Comprising one third of the world’s population, RCEP is estimated to be larger than the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and even bigger than the European Union and CPTPP countries combined.

Compared to existing ASEAN-plus-one agreements, RCEP is also poised to set a higher standard. With deeper commitments, RCEP countries may reap higher welfare gains in the long term. Studies show that the welfare gains of the original RCEP countries will increase between 2020 and 2030 and that the gains will be varied. Korea, for example, may achieve welfare gains of about 3.4% by 2030.[2] The welfare gains were also expected to increase drastically, with the assumption that non-tariff barriers (NTB) in services and logistics will be cut by 20%.[3] In the near and medium term, however, adjustment costs inevitably will be incurred, resulting in lower gains for some members.

RCEP would also be influential in streamlining the existing FTAs and improving the “noodle-bowl” effect experienced by the region. The alphabet soup of bilateral or multilateral FTAs – and their different level of commitments – has increased the costs of trade in the region. RCEP can reintroduce efficiency.

RCEP will not be able to eliminate complications stemming from existing agreements. However, it can standardise and harmonise discipline issues related to rules of origin, dispute settlement, competition, intellectual property rights, and e-commerce. Such predictability would be comforting to investors.

Indeed, RCEP will be significant regionally and globally, especially as it seeks to transform existing global value chains (GVCs) into more seamless hubs with lower trade costs once non-tariff barriers are eliminated.[4]

Some studies show that countries without existing FTAs among RCEP partners will benefit more than existing trade partners of RCEP members. The development gap among member countries also matters, However, RCEP extends special and differential treatment to lower-income ASEAN Member States, especially Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Viet Nam.

Large but incomplete

RCEP’s 20 chapters are heavily focused on traditional trade chapters, such as market access in goods and services, and competition. Arguably, however, RCEP is distinguished by what it doesn’t contain.

Three gaps are particularly glaring. The first one concerns state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Unlike the CPTPP, RCEP does not include specific provisions to prevent SOEs from crowding out local and foreign firms in the domestic market. Provisions in the competition chapter would, to a certain extent, address this issue. However, there are no specific rules by which SOEs will be governed.[5]

To date, the dominant presence of the SOEs in the region have allowed them to enjoy a near monopoly in domestic markets. Local SMEs are often unable to compete. The lack of a level playing field which surrounds government procurement further complicates the issue. Without a chapter on SOEs, governments can award projects based on their own mechanisms, processes, and standards without much transparency.

The absence of a labour chapter in RCEP is also significant. Such a chapter would outline provisions to address the rights of workers – both skilled and unskilled – in terms of wages, working conditions, and union participation and empowerment. Labour provisions would also address issues of exploitation and human trafficking, which is particularly rampant among unskilled workers. Other public policies that would be impacted by labour provisions include reforms of immigration policies in participating countries.

Finally, the absence of an environment chapter may lead to negative and unintended results, depending on the implementation and governance processes by member countries. An environment chapter is urgently needed, given the criticality of overfishing, overlogging, and illegal wildlife trade in the region. ASEAN has the opportunity to push for a collective elimination of these unsustainable practices.

Optimists say that RCEP may be upgraded in the future. Indeed, the sooner ratification ensues, the sooner members can include more non-traditional trade chapters such as those outlined above. If or when that takes place, RCEP may become more aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals.

Facing shocks through greater integration

RCEP also offers its members the benefits that can come from greater regional integration. The Covid-19 pandemic proves once again that collaboration across borders is essential.

The negative economic impact of the pandemic was expected. What was less expected was the increasing inward-looking policies adopted by RCEP members.

Take, for example, the policies around personal protective equipment (PPE), from masks to hand sanitizers. As anticipated, lockdowns stifled economic activity and disrupted supply chains. Restrictions in China, a critical supplier of PPE, led to supply shocks in countries around the world.[6] Many governments also adopted similar emergency policies such as restricting exports of PPE, medical goods, and food products. As trade partners retaliated, price hikes and volatility ensued, as did supply shortages.

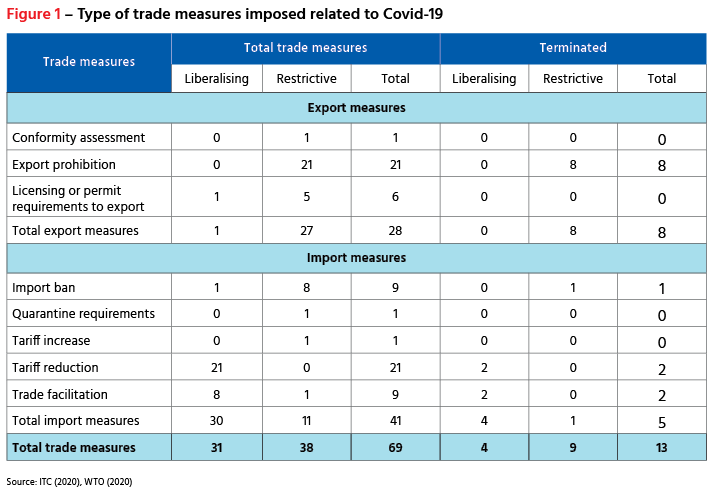

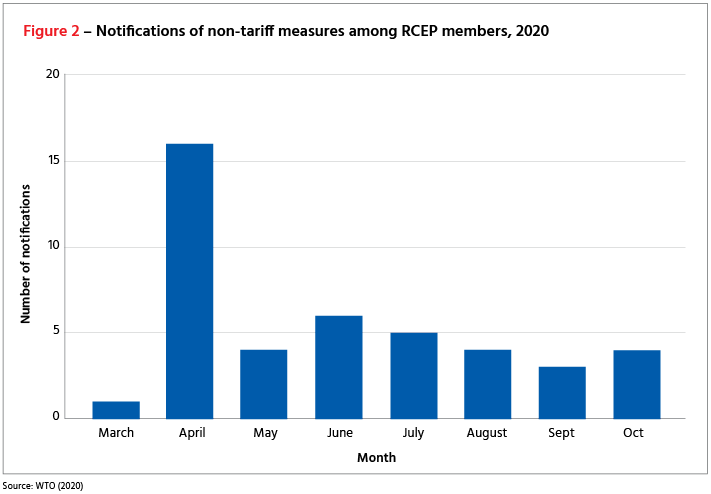

Non-tariff measures (NTMs) proliferated during the pandemic. From February 2020 to October 2020, 66 trade measures were implemented by RCEP countries; 35 measures were classified as restrictive (see Fig. 1).[7] From a list of 24 export restrictive measures, 19 were export prohibitions. The number of notifications for NTMs peaked in April 2020 (see Fig. 2).

It should be noted that 21 out of 30 of the liberalization import measures were tariff reductions.

Thus, despite high demand, reducing tariffs on PPE products did not attract more imports. The adoption of export prohibition measures ensured that enough PPE were available domestically.

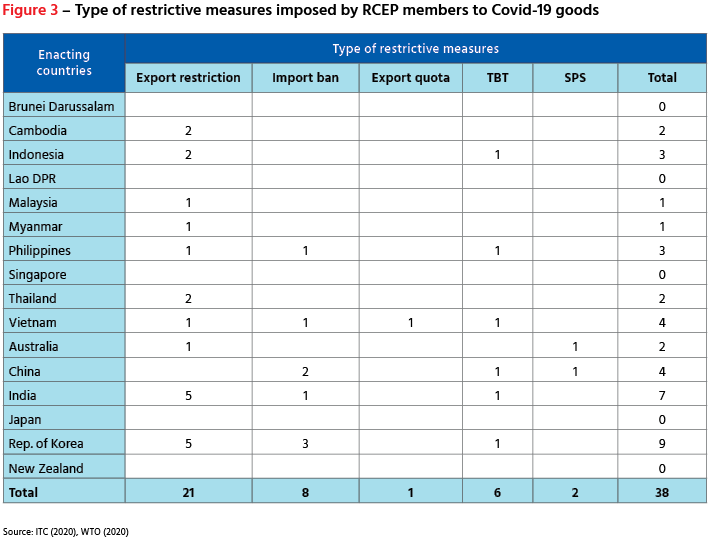

Another widely adopted restriction was the import ban. To curb the spread of the virus, import bans were also imposed by countries with restrictive sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regulations. Predictably, wild animals from China accounted for most of the banned products. The Republic of Korea (ROK) imposed the highest number of import bans, all on wild and live animals (see Fig. 3).

These restrictive measures were supposed to be temporary. However, uncertainties surrounding the virus prompted RCEP members to implement an unknown termination date. From February to October 2020, only nine out of 35 restrictive trade measures were terminated, and only eight of them were termination of export restrictions.

Once RCEP is implemented, policy coordination in the region will hopefully improve – and improved certainty can help to mitigate and minimise pandemic-related shocks, from unemployment to corporate bankruptcy and financial market fragility.[8] If member countries commit to cooperate and support each other during these uncertain times, RCEP can serve as a platform for recovery.

Ratification in 2022?

Four countries swiftly ratified the RCEP in 2021. Thailand stepped up first, in February. Singapore, China, and Japan followed by April 2021.[9] If the country’s pandemic response successfully curbs infections, Viet Nam may be the next in line to ratify. Indeed, RCEP members are all trying to curb the spread of the Delta variant, which has led to more lockdowns and closures of Parliaments. With limited resources, most countries are not prioritising ratification.

In Malaysia, a small open economy, there is an urgency for ratification to take place. Yet due to a weak government and a strong virus, ratification is not top of mind. As a new Cabinet is being rebuilt, containing the pandemic will be the ultimate litmus test for Malaysia’s new Prime Minister – not RCEP. On the contrary, RCEP’s outlook will depend on how the new government assesses the benefits that Malaysia will accrue from joining the pact.

A similar chain of events followed the signing of the CPTPP. Due to the changes in Malaysia’s leadership, the CPTPP has not been ratified despite having entered into force. As such, the trade deal is benefitting other countries in the region, such as Viet Nam and Singapore, and Malaysia is, once again, left behind.

Myanmar is also troubled by political instability since the military seized power from the elected government in early 2021. As protests continue, the ratification and tabling of provisions is uncertain.[10]

Perhaps after this wave of infections dissipates, governments can function in a new normal and ratification of RCEP picks up pace. RCEP members can then look forward to further cooperation in new, non-traditional trade areas, when the upgrade of the RCEP takes place in a hopefully not too distant future.

[1] - Mohamad & Cheng. 2020. “The RCEP: What this means for ASEAN and Malaysia”. ISIS Policy Brief, Issue 6-20. www.isis.org.my/2020/11/17/the-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep-2/

[2] - Lee, H. and K. Itakura (2015), Applied General Equilibrium Analysis of Mega-Regional Free Trade Initiatives in the Asia-Pacific. http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ospwpaper/15e001.htm

[3] - Ibid.

[4] - OECD (2018), Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2018: Fostering Growth Through Digitalisation, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/9789264286184-en.

[5] - New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. n.d. “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership text and resources”. https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership-cptpp/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership-text-and-resources/

[6] - Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (2020), ‘COVID-19 and Southeast and East Asian Economic Integration: Understanding the Consequences for the Future’, ERIA Policy Brief, No. 2020-01, April 2020, Jakarta: ERIA. https://www.eria.org/research/covid-19-and-southeast-and-east-asian-economic-integration-understanding-the-consequences-for-the-future/

[7] - ITC (2020), Market Access Map, https://www.macmap.org/covid19

[8] - Kimura, F. (2020), ‘Exit Strategies for ASEAN Member States: Keeping Production Networks Alive Despite the Impending Demand Shock’, ERIA Policy Brief, No. 2020-03, May 2020, Jakarta: ERIA. https://www.eria.org/publications/exit-strategies-for-asean-memberstates-keeping-production-networks-alive-despite-the-impendingdemand-shock

[9] - China Briefing (2021), What is the Ratification Status of the RCEP Agreement and When Will it Come into Effect?, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/ratification-status-rcep-expected-timeline-china-thailand-already-ratified

[10] - https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/anti-military-protests-myanmar-anniversary-1988-uprising-2021-08-08/

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).