Published 16 January 2024

The WTO customs moratorium on e-commerce could end in the February WTO ministerial. As always, most of the burden of such a move will fall on those least able to manage additional costs.

In the folk tale “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” a young boy has been raising alarms about a wolf for so long that, by the time a wolf actually appears on the scene, no one is paying attention to the boy anymore.

In the real world, businesses should know that the wolf is currently at the door: a key digital trade rule is likely to end in February with real-world consequences for companies and consumers.

The rule is formally known by its awkward name of the “customs moratorium on electronic transmissions.” What it means is that the 164 members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreed not to impose customs duties or tariffs on electronic transmissions. While the terms are still under debate, it effectively means digital services. Every few years since 1998, members have agreed to an extension of the moratorium.

After coming under serious threat two years ago, it now looks like the moratorium will be unlikely to survive the February WTO Ministerial Conference (MC13). It’s impossible to know the impact of the removal of the moratorium but it will probably drive up the costs of digital services into and out of many markets with large compliance costs landing especially heavily on smaller firms.

When it was launched in 1995, the WTO included very few rules that directly apply to digital trade. It was the dawn of the internet era and members were not certain exactly how this new development would unfold.

Just a few years later, however, it had already become obvious that internet-enabled activities had the potential to make a difference to trade in goods and services. Starting in 1998, members agreed to open a work program on electronic commerce. The effort did not get very far.

However, members did manage to deliver one important rule: to stop themselves from imposing tariffs on electronic transmissions. Members could see that some products formerly delivered in physical formats, like music or software or books, might be transferred electronically in the future.

As products transitioned from being clearly “goods” crossing borders and subject to tariffs to becoming digitally delivered items not covered by tariffs, it became an increasingly open question about how to handle the customs implications of, for example, software crossing a border on a floppy disk as opposed to via some other digital mechanism. A tariff might be applied to the disk itself, but not to the software loaded on the disk. Fully digital delivery, like software downloads from the cloud, has only added complexity to the issue.

The deliberately vague term “electronic transmissions” was originally chosen because many members were not keen to spend negotiating time clearly defining what was included and what might not be captured by a definition. It was still early days of the digital revolution and members wanted to maintain flexibility to see how the process might unfold.

Members were unclear about how exactly customs duties could be imposed on such transmissions. But many saw the risks of trying to replicate customs procedures for a new digital era. Hence, the solution was to impose a moratorium on the imposition of any tariffs on a temporary basis. The provision has had to be reaffirmed or extended at every WTO Ministerial Conference or the moratorium dies and tariffs can be applied to electronic transmissions.

At the outset, renewal of the moratorium was nearly automatic. But some members have grown increasingly concerned about the possible loss of revenue from cross-border digital trade and the potential for collecting duties on some volume of transactions, especially in the wake of a boom in cross-border delivery of goods and services enabled by the internet during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many WTO member governments and customs offices spy potentially juicy revenue targets by applying tariffs in novel ways. Many governments do not anticipate negative effects on their own firms by applying duties, and expect their efforts to only impact large multinational companies.

Working out the details about what might happen to revenue collection and trade has been difficult, with dueling projections of the risks and benefits of changing customs procedures. The most recent assessment, conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, shows extremely minimal economic revenue is likely from collecting tariffs on digital products.

Part of the challenge in determining the consequences of a collapsing moratorium is the difficulty in figuring out exactly how customs officials would collect duties from electronic transmissions. Customs officials have not been involved in managing services transactions nor are most offices set up in any way to do so.

But it is possible to argue that identified transmissions should be handled the same way as cross-border goods delivery. Firms will have to fill out customs forms, submit these documents to customs authorities, and prepare to pay duties (and probably domestic taxes) on transactions. The burden will fall mostly on services firms that have not had prior experience managing customs transactions.

Although it is not yet clear exactly how governments might opt to classify covered transmissions, Indonesia, as one example, has already opened up new tariff classifications for online books, music, software, and one called “other.”

The category “other” is particularly worrisome, as there are a wide range of cross-border services that could be captured including everything from online education and webinars to consulting services to cloud-based applications. Given the lack of detail in the original formulation at the WTO, members could be free to decide what sort of categories to include in future duty collection.

Of course, not all (or even many) governments will be interested in or able to implement these procedures. Many governments are parties to bilateral or regional trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) that include a permanent customs moratorium, so no matter what happens in the WTO, members have promised not to impose such policies. Others, like participants in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), have agreed to follow WTO rules which means that if the moratorium falls in the WTO, RCEP participants will be free to impose customs duties.

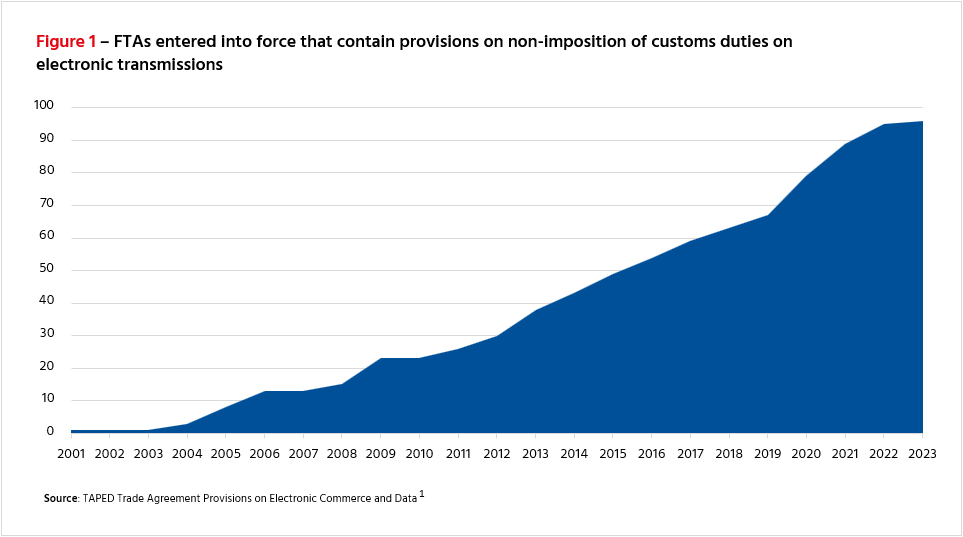

As Figure 1 shows, 96 existing trade agreements include commitments that mention the moratorium. Some have already pledged to make the moratorium permanent in one or more free trade agreements. Others, like Indonesia and the Philippines, have taken no commitments on the policy beyond RCEP.

WTO members that are currently part of the Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on Electronic Commerce, a subset forum of 90 economies, have included a commitment to make the moratorium permanent for signatories. However, until the negotiations are concluded, there is still scope for adjustment including to remove or make the JSI language on the moratorium flexible.

Other governments that are not participating in the JSI may decide to open tariff lines for the collection of digital duties. Firms should brace for requests to deliver customs revenue and follow new customs procedures. Those that fail to comply could easily be subject to fines and penalties—now and retroactively.

The real shame is that most of the burden of the end of the moratorium will fall, as always, on those least able to manage additional costs. This includes a wide range of smaller firms and consumers that could suddenly have to pay significantly more for imported services or find key markets serviced by platform providers becoming more expensive to access.

As a final insult, while concerns about revenue are not misguided, there are other ways to address these worries, including the use of value-added taxes (VAT), which would be more trade-facilitating and likely less damaging to developing countries and smaller firms.

Groups including many chambers of commerce around the world have spent considerable time warning about the dangers posed by the collapse of the moratorium heading into previous WTO ministerial conferences.

This time around, however, the topic has gotten less attention. It appears that many businesses are fatigued with the number of issues on the trade agenda and therefore aren’t fighting the momentum against the moratorium, or have decided that bilateral and regional trade agreements provide a sufficient bulwark against the damage that could be caused by the imposition of customs duties on digital trade. With the next opportunity for WTO members to decide on the moratorium just six weeks away, it is a growing gamble to assume that members will agree to roll over the topic one more time.

***

[1] Mira Burri, Maria Vasquez Callo-Müller and Kholofelo Kugler, TAPED: Trade Agreement Provisions on Electronic Commerce and Data, available at:

https://unilu.ch/taped. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).